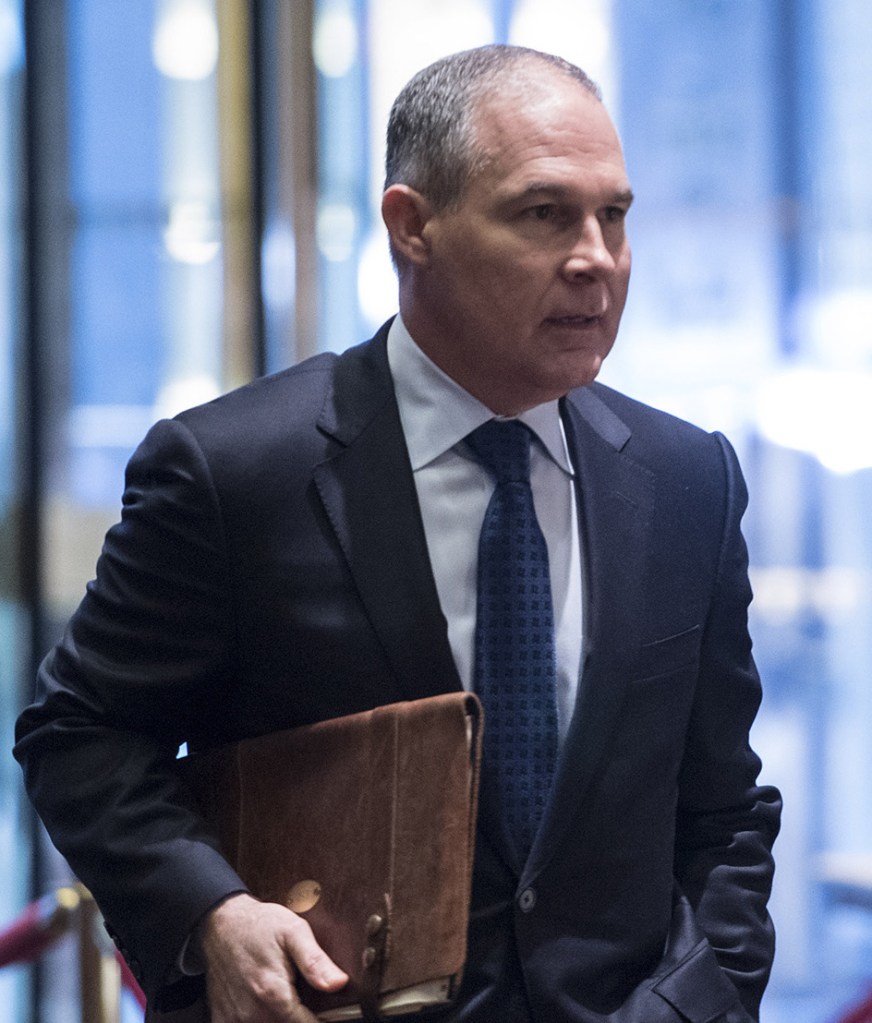

WASHINGTON — Two of Scott Pruitt’s top aides provided fresh details to congressional investigators in recent days about some of his most controversial spending and management decisions, including his push to find a six-figure job for his wife at a politically connected group, enlist staffers in performing personal tasks and seek high-end travel despite aides’ objections.

The Trump administration appointees described an administrator who sought a salary that topped $200,000 for his wife and accepted help from a subordinate in the job search, requested aid from senior EPA officials in a dispute with a Washington, D.C., landlord and disregarded concerns about his first-class travel.

The interviews conducted by staffers for the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee late last week shed new light on the EPA administrator’s willingness to leverage his position for his personal benefit and to ignore warnings even from allies about potential ethical issues, according to three individuals familiar with the sessions, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

The EPA’s former associate administrator for the Office of Policy, Samantha Dravis, spoke to Republican and Democratic aides for several hours Thursday, followed by Pruitt’s chief of staff, Ryan Jackson, on Friday.

Both aides described instances in which their boss pressed to travel first-class or via private jet, while Dravis acknowleged that Pruitt asked his subordinates to do non-official work for him, multiple individuals said.

Dravis’ attorney, Miller & Chevalier’s Andrew Herman, said in an interview Monday that his client answered questions from Republicans and Democrats “as forthrightly and candidly as she could, and she pushed back on both sides when they were either wrong or pushing their agenda.”

“I don’t think she was trying to protect anybody, and I don’t think she was trying to hurt anybody,” Herman said. “She was giving her view of what happened.”

According to an individual with knowledge of the matter, Dravis told congressional staffers that Pruitt initially asked her to contact the Republican Attorneys General Association – a group Pruitt had once led and Dravis had worked for before coming to EPA – as part of the job search for his wife. Dravis said she declined to make that call to avoid any potential conflicts of interest or possible violations of the Hatch Act, which limits federal officials’ political activities.

The new accounts by Pruitt’s handpicked staff come as EPA’s chief ethics officer, Kevin Minoli, has urged the agency’s Office of Inspector General to broaden its review of Pruitt’s conduct. Minoli told the Office of Government Ethics in a letter dated last Wednesday that he suggested the move after “additional potential issues regarding Mr. Pruitt have come to my attention through sources within the EPA and media reports.”

Don Fox, former acting director of the U.S. Office of Government Ethics, said in an interview Sunday that the fact that the administrator asked federal employees to perform multiple tasks unrelated to their official work raises serious questions about whether the EPA administrator has violated federal rules of official conduct.

“Pruitt is the gift that keeps on giving in terms of examples of how senior government officials, particularly in this administration, abuse their power and their position,” Fox said, “and really treat the government’s resources – of which the most valuable are personnel – as personal servants.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story