At the Taste of Eden restaurant in Maine’s western mountains, the menu is vegan and its farm-to-table vegetables are grown using vegan methods, too.

“When the whole mad cow thing came out, I became much more aware of what we are putting on our food source” in terms of fertilizer, said Sonya Tardif, who owns the Norway restaurant with her husband, Michael Tardif.

Before the mad cow news broke (which revealed that cattle being infected with the transmissible brain-wasting disease was caused by feeding them the carcasses of other animals), the Tardifs had used conventional farming methods on their plot at Sonya’s grandparents’ farm in West Paris. For fertilizer, they used rock phosphate and cow manure.

Soon Tardif started investigating where agricultural inputs come from. While rock phosphate fertilizer is mined from the earth, cow manure comes from cattle kept for either the dairy or slaughterhouse market. In addition to manure, many common agricultural soil amendments are derived from animal products and include bonemeal, blood meal, fish emulsion and slaughterhouse wastewater sludge.

Eight years ago, the Tardifs switched to all veganic methods.

Now the restaurant’s soups, pot pies and chickpea alfredos always contain farm-to-table veganic produce such as green beans, peas and carrots. During Maine’s growing season, other menu items – such as salads – feature veganic vegetables including lettuce, kale, cucumbers and corn.

Called veganic farming, vegan organic gardening and vegan permaculture, this style of growing uses plants rather than animals to build soil fertility. It’s still a niche practice, but last summer the headline of a Civil Eats story asked “Is Vegan Farming the Next Plant-Based Phenomenon?”

A handful of farmers (and an unknown number of home gardeners) use this practice in Maine.

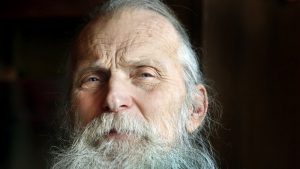

Nationally, one of the leading experts on veganic farming is Will Bonsall of Industry. Best known for his seed-saving work, Bonsall has been cultivating Khadighar Farm without animal products for more than 40 years. He’s also the author of “Will Bonsall’s Essential Guide to Radical, Self-Reliant Gardening,” which emphasizes vegan techniques.

Bonsall credits his “obsession with self-reliance,” interest in sustainable living, appreciation for organic farming, and an allergy to ruminant meat with propelling him toward vegan eating and farming. About five years after starting the farm in 1971, he began to question the conventional wisdom around obtaining fertilizer from animals.

“I’m going to grow my own food, grow my own seeds, what the heck, what about the fertility?” Bonsall said during a recent phone interview when describing his path to veganic farming. “Is there any reason the land can’t grow its own fertility?”

Bonsall soon discovered the land can grow its own fertility.

The key is using plant-based mulches and compost. Bonsall favors twigs and branches that have been chipped, leaves that have been shredded and hay. He uses most of the leaves for mulch and composts all the rest of the plant material.

Commenting on cow manure, which he used in his first years of farming, Bonsall said: “It is the grass and the grain that the cow ate that is the ultimate fertility.” To achieve optimal fertility in the hay he grows, Bonsall said he doesn’t limit the plant species in the field the way dairy farmers do.

“My pasture has goldenrod and asters,” Bonsall said. “I want biomass and weird herbs for better biodiversity and minerals.”

Tardif at Taste of Eden said she buys vegetable-based compost from Earthworks in Mechanic Falls. She also uses alfalfa pellets, molasses and seaweed.

Across the state in Brooksville, Sweet Dog Farm grows and occasionally sells veganic fruits and vegetables from its farm stand. Its crops are fertilized with plant-based compost, seaweed, granite dust and a “tea” made from comfrey, weeds and seaweed. The farm’s compost is made by layering seaweed, shredded leaves, mulch hay, grass clippings and finished compost.

“We do it because we do not want to have anything to do with the exploitation of animals,” said Doris Groves, who runs Sweet Dog Farm with her partner, Bob Jones. “It is not complicated, and anyone could do it.’

Tardif agreed and recommended gardeners “start small if you don’t have much experience. And start with some of the easier to grow vegetables like greens, kale and tomatoes.”

The result will be your own 100-percent vegan vegetables.

Avery Yale Kamila is a food writer who lives in Portland. She can be reached at

avery.kamila@gmail.com

Twitter:AveryYaleKamila

Comments are no longer available on this story