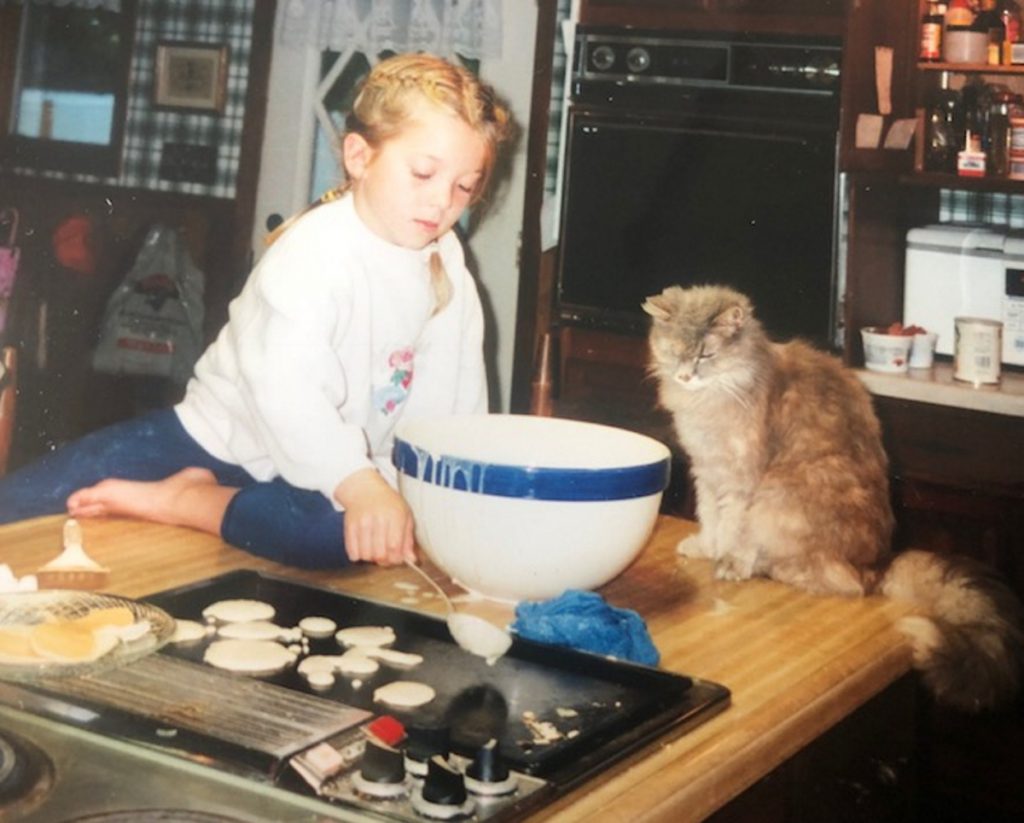

Michelle Gardner came home from work one day and found her son, Christopher Harris, in the kitchen making homemade pasta, rolling and cutting it by hand. He was in middle school.

Harris didn’t care for a lot of the food his mother prepared – Gardner was “kind of a health nut,” she says herself – so, inspired by a home ec class required at school, Harris took matters into his own hands.

It was no passing fancy. Harris went on to work at high-end restaurants in his hometown of Kennebunk and in Portland, opened (and closed) his own Old Port restaurant, and in March appeared on the Food Network cooking competition show “Chopped.”

His mother could not be prouder. Especially of his Pasta Bolognese and his “phenomenal” meatballs.

Sunday is Mother’s Day. Chefs have moms, too, obviously. So we wondered: Back when the rest of us were handing our moms lame homemade cards and flowers we picked from her own garden, were chefs-to-be dazzling their mothers with gourmet dinners? Did their moms see any signs that their little one would overtake their parents in the kitchen one day?

PASSION, AND PASSION FRUIT

Sometimes the signs were as clear as consommé.

Ilma Mendoza, mother of Ilma Lopez, chef/co-owner of Piccolo and Chaval in Portland, says when her daughter was just 4 or 5 years old and living in her native Venezuela, she asked for baking equipment for her birthday. When she turned 10, she asked to be taken to “a real restaurant” – no fast food – with good service.

Ilma Lopez recalls that it was a high-end French restaurant run by chef Pierre Blanchard. And she still remembers little details. It was the first time she ever got an intermezzo – a palate cleanser between courses, in this case passion fruit sorbet served on white porcelain.

Mendoza doesn’t like to cook herself, but says she always enjoyed being in the kitchen with her little girl because Lopez would get so excited, putting “her heart and emotions” into her cakes, cupcakes, cookies, pasta and salads.

Laura Richter is the mother of Avery Richter, the executive chef at Portland caterer Black Tie Company. Avery grew up on Great Pond, in the Belgrade Lakes. On Mother’s Day, Avery and her brother would “always bring me breakfast in bed,” her mother said. “It was scrambled eggs and fruit on a tray, with some flowers.”

Avery Richter grew up helping her mother prep meals and take care of their garden, and she went fishing, hunting and clamming with her family. (Her father is a fisheries biologist, and her brother grew up to become a Registered Maine Guide.) Even as a small child, the seed had already been sown: Laura Richter recalls finding a questionnaire Avery filled out in school as a kindergartener. “What do you want to be when you grow up?” it asked. Avery had scrawled “A cook.”

As a teenager and young adult, Avery worked with a chef at a local inn, scooped ice cream at a local dairy bar, and had a booth at the local farmers market selling baguettes and blueberry coffee cake. After she graduated from the University of Maine with a degree in food management, her parents bought her a food cart, and she sold wraps and smoothies.

“She just always did it,” her mother said, “and I think she realized that was just her natural place.”

PETS AND PICKY EATERS

For the mothers of these chefs, predicting their kids’ futures was relatively easy. Other moms say the clues were as hard to find as a fast-food french fry in a five-star restaurant.

JoAnn Kelly always got a card and flowers from her three children on Mother’s Day. She says she had no idea that one day her middle child would be a chef, much less a James Beard Award winner. She thought Melissa Kelly, now chef/owner of Primo in Rockland, would become a veterinarian. The family bred Siberian huskies, and also had cats, fish and frogs to care for.

“She did love animals,” JoAnn Kelly recalled, “and I always thought she would go in that direction.” Long pause. “But she did love to eat.”

The family lived its own version of a farm-to-table lifestyle on Long Island, New York, which must have influenced chef Kelly since today she is known for her farm that raises 80 percent of the food she serves at Primo. They gardened, fished, and made everything from scratch, more from necessity because times were tough, than love of food or the land, JoAnn Kelly says – her husband was in the Navy, they didn’t have a lot of money, but they had three children to raise.

After graduating from high school, Melissa told her mother she wanted to take a year off. JoAnn Kelly agreed, on the condition that her daughter get a job. Melissa did, working as a waitress in a nice restaurant, where she would steal away to work in the kitchen and ask the cooks questions. “That’s when she started getting interested in food,” her mom said.

When the year was up, Melissa Kelly told her mother she wanted to enroll in the Culinary Institute of America, which is in Hyde Park, New York. JoAnn Kelly and her husband had moved to Maine by then, so Melissa Kelly moved in with her maternal grandfather, whose name was – drum roll – Primo. She commuted to school and lived with Primo on weekends, when they would visit the markets and cook together.

By then, JoAnn Kelly said, her daughter “had this insatiable love for the culinary arts. She still does.”

Cindy Stevens says her daughter, Shelby Stevens, who is executive chef at Natalie’s in the Camden Harbour Inn, grew up wanting to be a basketball player or marine biologist. Of Stevens’ four children, Shelby was the least adventurous about food. When the family went to a school function or potluck, Cindy Stevens recalls, “she would always ask ‘What did you make, because that is the only thing I’m going to eat.’ ”

Shelby did like to help her mother in the kitchen, though, and baked lots of Christmas cookies. (To this day, according to her mother, the chef keeps cookie dough in her freezer so she can slice and bake fresh cookies at a moment’s notice.) Cindy Stevens said she realized her daughter’s casual interest in cooking might turn into her life’s work when the girl was in middle school, and mother and daughter started taking classes together – a cheese class here, a bread class there. “She definitely outperformed me,” Stevens said.

Eventually, Shelby became interested in learning how ingredients are put together, and got encouragement and motivation from a culinary arts teacher at Mt. Blue High School. She brought her mother along on a tour of the New England Culinary Institute in Montpelier, Vermont, and her path to a professional kitchen was set.

BRINGING HIS WORK HOME

Christopher Harris’ interest in cooking did not stop with middle school home ec class. In high school, he worked summers in Kennebunk restaurants, including Windows on the Water and the White Barn Inn. He started out doing prep work – as well as bartending, serving and washing dishes – and worked his way up. Sometimes he’d get to create his own specials.

“I remember him saying ‘I need to have you try my tuna because I’m doing the special tonight, and this is going to knock your socks off,’ ” his mom said. ” ‘I know you don’t like fish, but keep an open mind and give it a try.’ He did experiment with food and try to introduce me to things I wasn’t particularly fond of.”

Gardner also recalls her son excitedly coming home one day and telling her he had cooked for George and Barbara Bush, an experience he would have more than once.

“They called him over to the table and told him how wonderful the lobster ravioli was,” she said.

When Harris opened Crooners & Cocktails in Portland’s Old Port, the whole staff got tattoos of the restaurant’s logo. At the restaurant’s first anniversary, Gardner told her son that if he made it to his second year, she would get one too. She kept her promise.

Harris, now head chef at Gritty McDuff’s in Portland, still shies away from his mother’s holistic dietary preferences, just as he did in middle school, but recently tried a ketogenic (low-carb) pizza she made. His mother reports that Harris was “really surprised at how tasty it was.” She’s not intimidated by the thought of cooking for a professional chef.

“He’s going to eat what I put in front of him, and that’s the way it is,” she said. “I’m his mother.”

Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at:

mgoad@pressherald.com

Twitter: MeredithGoad

Comments are no longer available on this story