“Industrial Maine: Our Other Landscape” is fittingly installed in the Atrium Gallery, a lobby teeming with people at University of Southern Maine’s campus in Lewiston. Curated by painter Janice L. Moore, the show includes 70 works about the state’s industrial landscape. Well, there were 70 works, but that number has dwindled by three; we’ll come back to that.

“Industrial Maine” is led by paintings of industrial scenes such as factories and storage tanks, joined by photographs, monotypes, collages, assemblages and sculptures. The show is generally strong with a few blazing bright spots and surprises. It is a bit mixed, but it has the feel of being just a round or two of edits away from a solid standard of excellence.

Some of the strongest work is the farthest from the front. I think Gail Skudera’s three silver-framed woven image multi-media works are the most intriguing and elegant in the show, but they hang down a hallway almost as an afterthought. Skudera’s images are subtle: The weaving of the images and materials on the surface echo like ghostly ripples on a lake of memory, quietly calling to the weavers who once drove the industry in Lewiston’s fabric factories. And next to Skudera’s work, away from the epicenter, are a similarly strong lightning-energized but almost apocalyptically gray power-grid landscape by Dennis Pinette (who does have other pieces in the main room), and Bronwyn Sale’s best work (she, too, has works in the front), a misty image of a soft gray house with poetically rhythmic metal forms, still and staid as though frozen in a moment of understated pageantry.

To a certain extent, I have changed my thinking about artists including their own works in shows they curate, but this particularly applies to people like Moore who are full-time artists who just happen to curate a show now and then. Moore is a painter rather than a professional curator, and we can feel that in several quiet ways.

The subject of Maine’s industrial spaces, reclaiming them and honoring their place in our social and cultural history are Moore’s artistic passions. That she can empathize with the included artists adds a bit of moral clarity to “Industrial Maine” where other curatorial eyes might have (and maybe should have) looked more coolly at the subject. Moreover, whereas professional curators have to approach their communities with an eye to objectivity, Moore’s efforts have taken the form of her growing her community of like-minded peers. Moore’s own paintings have a primitivist charm; her portrait of the B&M Baked Bean factory, for example, is painted in a style closer to 19th-century portraits of ships than the bold brushiness of what we typically associate with ambitious Maine painting. But this too is fitting; those ships, after all, were very much the core of Maine’s industrial connections to the rest of the world. However unintentionally, Moore’s own work feels like the capital letter at the start of a sentence.

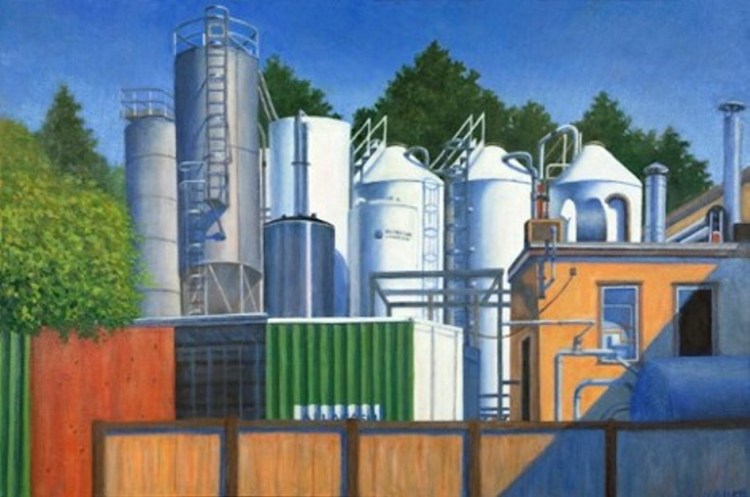

Work by Dennis Pinette

With Pinette and a few of the stronger artists like Nina Jerome, “Industrial Maine” crosses the imagined aisle back toward expectations associated with traditional (and traditionally strong) Maine painting. Maine’s landscape is just as often presented as the hardscrabble working waterfront as anything else. And that aesthetic is at play here: Jerome’s “Winter Power #8 Illusion” greets the entering viewer. It’s a dynamically brushed oil on canvas in which the steam and exhaust from a factory lights up the early morning winter sky with flaming lemon, raspberry and tangerine edges under the night blue heavens and above the unlit black of the landscape, above which march the slender poles of power lines like silhouetted soldiers tramping toward their chimneyed citadel.

Work by Nina Jerome

The most exciting points of “Industrial Maine” come as surprises. Crystal Cawley’s handsome and unexpectedly poignant trio of handmade paper “thinking caps” are about child labor. One features the collaged pages of a girl’s arithmetic notebook from 1922. Another features the 1913 “Declaration of Dependence” published by the National Child Labor Committee.

Most impressive to me, and unlike anything else in the show, is Dan Dowd’s pair of wall assemblages hung on the two opposing walkways curving into the space. Both are found wooden boards wrapped with three strips of cast-off tin at one end with an abandoned sweater or rain coat draped over the other end. Dowd has a rare ability to establish dignity in detritus. And his ability to make handsome assemblages out of unlikely materials almost hides (but not quite) a secret second project: The untitled black sweater piece might be a Glock handgun (or a shotgun?) while the raincoat piece resembles a submachine gun such as a Tech 9. Dowd’s work is deceptively subtle, nuanced and brilliant.

He hints at the outside edges of design intelligence, art object aesthetics and the history of assemblage to bring us fully back to Cubism and its focus on the minimal variables necessary for recognition – specifically in terms of labels like “gun.”

Most importantly, Dowd reaches to the kid in so many of us and our history of making play “guns” out of any stick or discarded thing that even remotely resembled a gun.

Work by Dan Dowd

In the wake of recent shootings in places like Parkland (or wherever it is next week), Dowd’s work feels urgent; in the context of “Industrial Maine,” it’s a reminder about the state’s history of gun manufacturing (e.g., Saco Defense) and, of course, that Maine is where that scourge of civilization, the machine gun, was invented.

The elephant in the room, however, is no longer in the room. Walking into the gallery, it’s impossible to miss the three blank spaces on the wall with picture hangers and notes, signed by Moore, that read: “This painting has been removed by order of the USM President.”

USM President Glenn Cummings had the works removed after receiving a complaint about showing the work of the artist, Bruce Habowski, because he is a sex offender – a decision Moore does not agree with (see Page A1).

While this situation regarding censorship and a criminal past might appear as merely an ugly set of interruptions with most exhibitions, it is oddly not out of place with Moore’s “Industrial Maine.” To begin, Moore’s project is driven by moral, ethical and historical urgency. But secondly, while Maine’s industry is missed in many ways, it’s a mixed bag: On one hand, many mourn the lost jobs and economic positives, but the exhibition also reminds us about darker issues such as child labor and pollution.

Moore’s “Industrial Maine” is not unlike Pinette’s “Power Grid”: spare, gritty, thoughtfully rendered in shades of gray, and surprisingly electrified.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story