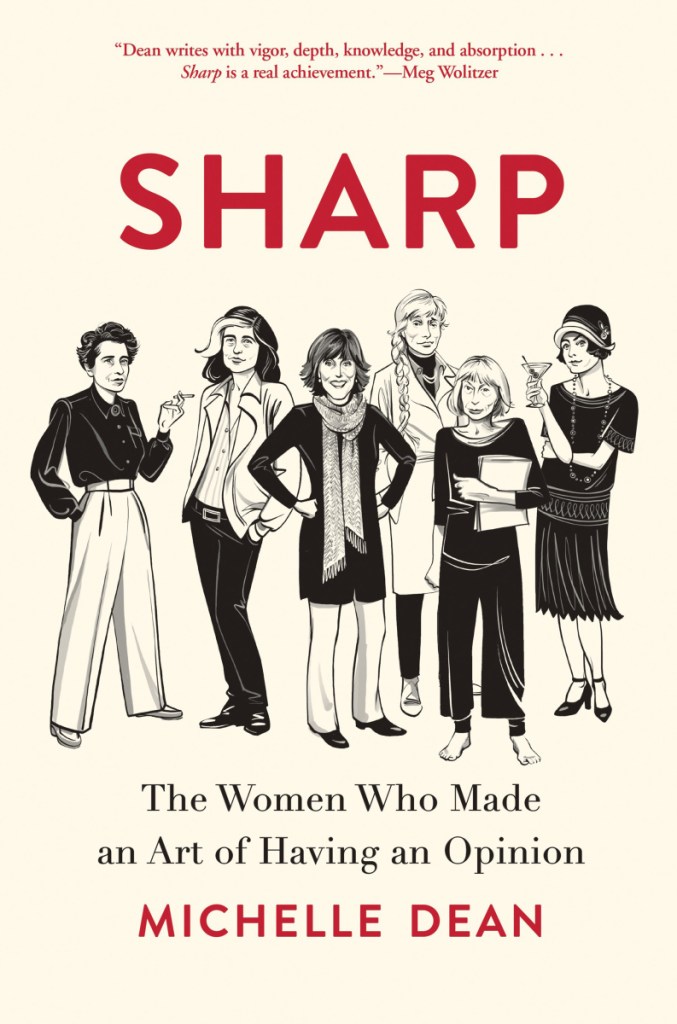

The 10 writers Michelle Dean surveys in her new book – Dorothy Parker, Mary McCarthy, Joan Didion, Hannah Arendt, Susan Sontag and Nora Ephron among them – were variously called “sharp” throughout their lives. The epithet described a forceful mode of speaking and writing. But it was also used as a rebuke: “Sharp” implied speaking and writing out of turn; behaving improperly, even rudely.

But these women more than held their own in the boys’ club of American letters. They wrote books and articles for The New Yorker and other prestigious outlets and made argument a way of life. “Through their exceptional talent, they were granted a kind of intellectual equality to men other women had no hope of,” Dean writes at the beginning of “Sharp: The Women Who Made an Art of Having an Opinion.”

Combining biography and criticism, Dean is often shrewd in her judgments. If early chapters on Parker and English journalist Rebecca West feel thin, Dean does show that these figures were nobody’s victims. The book picks up steam with Arendt and the debate over totalitarianism and the Holocaust. (Arendt covered the trial of Nazi Adolf Eichmann and wrote “The Origins of Totalitarianism.”)

Arendt found an unlikely ally in novelist and critic Mary McCarthy, a central figure here. McCarthy’s fiction (“The Group,” “Cannibals and Missionaries”) has not aged terribly well, but she wrote memorable sentences and literary criticism still worth reading. She was a notorious talker who shined in social settings yet had to put up with being called catty. Her critics, Dean writes, “did not like what she saw when she looked at the world, or at least they found her somehow impolite for recording it in prose.”

Film critic Pauline Kael, who got up everybody’s nose, was also accused of impoliteness. It’s a silly charge, of course – an instance of a woman being called out for behavior that would go unremarked upon in a man. In the New York literary world where most of these figures circulated, writing criticism meant pulling no punches.

Central to the arguments of their time, these writers are canonical figures, whose writing endures, period. Dean could stress this more robustly. Sontag’s musings on high culture were passionately discussed, while Joan Didion brought a cool touch to her reportage about California and elsewhere. Janet Malcolm’s controversial writings have called into question the very nature of journalistic practice.

Others, like Renata Adler, who famously eviscerated Kael in a New York Review of Books takedown, suffered a decline in reputation – though she is now enjoying a much-deserved revival with reissues of her nonfiction and the cult novels “Speedboat” and “Pitch Dark.”

Dean is sometimes at pains to place these figures in relationship to the feminist movement of the late 1960s and early ’70s. “I ran into quite a lot of people who wanted to cut these women out of history precisely because they took advantage of their talents, and did so without turning those talents to the explicit support of feminism,” Dean writes.

None were cause joiners in the conventional sense. Spectators and commentators, yes; sloganeers, no. Didion took on the politics of feminism in a 1972 essay. She found much what she heard to be childish if not naive. “These are converts who want not a revolution but ‘romance,’ ” Didion wrote. Here was another example of the sharpness that Dean finds in her subjects: a certain ruthlessness.

Dean hardly underplays the sexism and the condescension meted out to Kael and Co. “But sisters argue, sometimes to the point of estrangement,” she observes. The strength of “Sharp” lies in the way Dean stands up for the “individual personality” of each of her subjects. And they were individuals, all.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story