Canadian scientists have measured record-breaking temperatures in the deep water flowing into the principal oceanographic entrance to the Gulf of Maine, prompting concerns about effects on marine life.

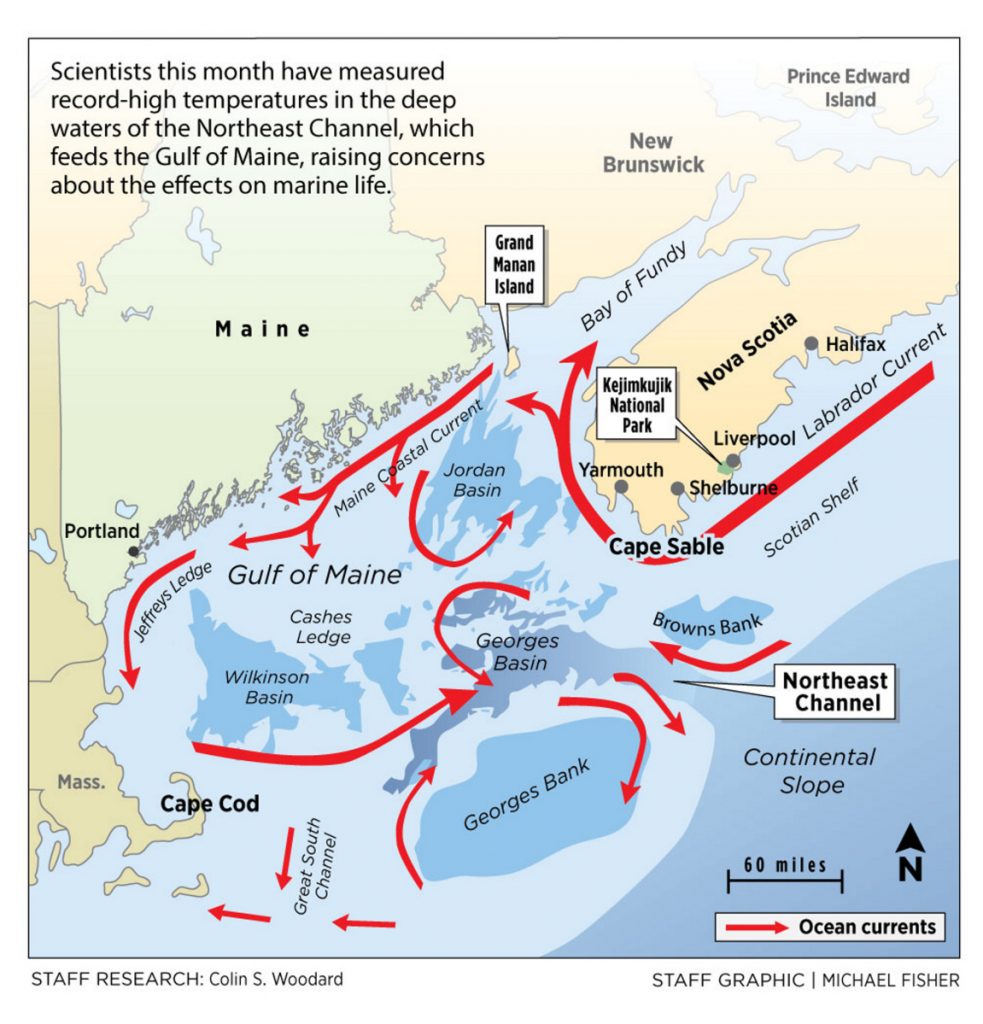

The deep current entering the gulf via the Northeast Channel – a deep passage between the Georges and Browns banks – normally consists of chillingly cold water originating off Labrador and Greenland, and contributes to Maine’s unusually productive ocean waters.

But this month researchers working from the Canadian Coast Guard cutter Hudson recorded temperatures exceeding 57 degrees at depths of 150 to 450 feet – nearly 11 degrees above normal for this time of year and the highest seen in 15 years of surveys.

“It looks like there’s a big rush of warm water going into the gulf,” said David Hebert, a research scientist at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, which undertook the research. “It was really surprising.”

Hebert’s team does surveys twice a year, and when they were last out in early December they also found record-breaking temperatures in Georges Basin, an important deep-water area inside the Gulf of Maine. The temperature there was 5 degrees above normal at depths of 600 feet and the highest in 40 years of readings, Hebert said last week.

Maine-based researchers say they also have been seeing indications that the gulf has been filling with unusually warm water in recent months, although it remains unclear exactly when the influx began and what the effects will be.

David Townsend, an oceanographer at the University of Maine’s School for Ocean Sciences, said they’ve detected warming via automated buoys extending as far as Jordan Basin, 25 miles offshore from Mount Desert Island, and that it appears to have started late last summer or early in the fall. His team has concluded it is the result of warm Gulf Stream water entering the Northeast Channel.

SUSPECTED LINKS TO GULF STREAM

The likely culprit, Townsend said by email: “reduced intensity of the Gulf Stream, increased frequency of warm core rings off New England and Nova Scotia, and arctic-melt water flows from the north.” Since the event doesn’t involve surface waters, it isn’t connected to local air temperatures, he said, but rather to global warming-driven changes to ocean currents.

Andrew Thomas, another oceanographer at UMaine, said the Gulf Stream appeared to be flowing farther north than usual. “What water is sitting right off the entrance of the Gulf of Maine at a given time is really decided by a battle between warm slope water coming from farther south and cold slope water coming down the Scotia Shelf, and whoever wins that battle is going to get into the Northeast Channel and the gulf,” he said.

“From Dave (Hebert)’s data, it looks like there’s a bunch of really warm water that’s just hanging out there,” he said, noting that it could take as long as a year for the water to be pushed to the surface and into Maine’s coastal areas.

An “ocean heat wave” in 2012 caused lobsters to shed six weeks ahead of their usual schedule, throwing off the timing of Maine’s soft-shell harvest and leading to conflicts with New Brunswick fishermen over access to Canadian lobster processing facilities. The population of green crabs exploded and they devoured most of the clams in Freeport, Brunswick and other towns, tearing up seagrass beds in many bays, while puffin chicks on Eastern Egg Rock starved because their parents couldn’t find appropriate food for them.

CONCERNS FOR MARINE WILDLIFE

Nick Record of the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in East Boothbay said he’s concerned that the current intrusion of warm water into deep-water basins may be bad for right whales and herring because both depend on swarms of Calanus finmarchicus, a rice-sized, fat-packed copepod. The deep-water population in the eastern half of the gulf, where endangered right whales until recently went in the late summer to fatten up, has been in decline.

“I’ve been seeing really warm temperatures especially in the deep basins where Calanus is, and at the time when right whales are in the eastern gulf,” Record said. “That’s the habitat the whales have abandoned in the last few years, so it may be connected to the changes in the deep water coming into the gulf.”

The new Canadian data came days after other scientists published research in the journal Nature indicating a key part of the Atlantic Ocean’s circulation has slowed to a new record low because of climate change.

The Atlantic meridianal overturning circulation, the scientists reported, has weakened by 15 percent since the mid-20th century. It is important to humans and marine life alike because it acts as a temperature regulator, bringing warm water from the equator to more northerly reaches like southern Iceland and western Europe, and cold water southward down through the deep ocean. It is at its weakest in a millennium, the researchers reported.

Colin Woodard can be contacted at:

cwoodard@pressherald.com

Comments are no longer available on this story