KENNEBUNKPORT — It was the summer of 1943 when the future Barbara Bush first visited Walker’s Point, the summer compound owned by her 18-year-old boyfriend’s grandparents.

War was on everyone’s minds, not least because young George H.W. Bush had just earned his pilot’s wings and would leave for the Pacific Theater in two weeks. Gasoline and tires were rationed, so they got around town in a wagon pulled by a horse named Barsil, and one of George’s brothers thought it would be funny to call the visiting girl “Bar.” The nickname stuck for life.

So did the 17-year-old’s budding romance with the lanky young aviator whom she’d met at a secondary school dance a year and a half earlier. They rode bikes, played tennis, collected seashells on the beach and bore teasing from his numerous family members.

At night, she later recalled, they walked out on the rocks alone, watched the moon come up and got secretly engaged, forging a partnership that would carry him and their eldest son to the White House, creating the most successful political dynasty in U.S. history.

Barbara Bush, who died Tuesday in Houston at age 92, was one of the most popular and respected first ladies in history, a woman with the impeccable manners, bearing and grace of America’s once influential Eastern establishment, the Ivy League-educated elite that once dominated American political and business leadership. A fierce defender of her husband and family, she was the central gravitational force of a wealthy and powerful family that reshaped America and the world, a tireless advocate for adult literacy and a lifelong lover of Maine’s rocky coast.

Mrs. Bush was suffering from congestive heart disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. On Sunday, Bush family spokesman Jim McGrath announced she had decided to stop seeking medical treatment to prolong her life. On Tuesday just before 8 p.m., McGrath released a statement announcing her passing.

“Laura, Barbara, Jenna, and I are sad, but our souls are settled because we know hers was,” former president George W. Bush, her son, said in a written statement Tuesday night. “Barbara Bush was a fabulous First Lady and a woman unlike any other who brought levity, love, and literacy to millions. To us she was so much more.”

“Mom kept us on our toes and kept us laughing until the end,” Bush continued. “I’m a lucky man that Barbara Bush was my mother. Our family will miss her dearly, and we thank you all for your prayers and good wishes.”

Son and former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush also issued a statement Tuesday evening. “I’m exceptionally privileged to be the son of George Bush and the exceptionally gracious, gregarious, fun, funny, loving, tough, smart, graceful woman who was the force of nature known as Barbara Bush,” he said.

Video: The flag at Walker’s Point in Kennebunkport is lowered in honor of the first lady.

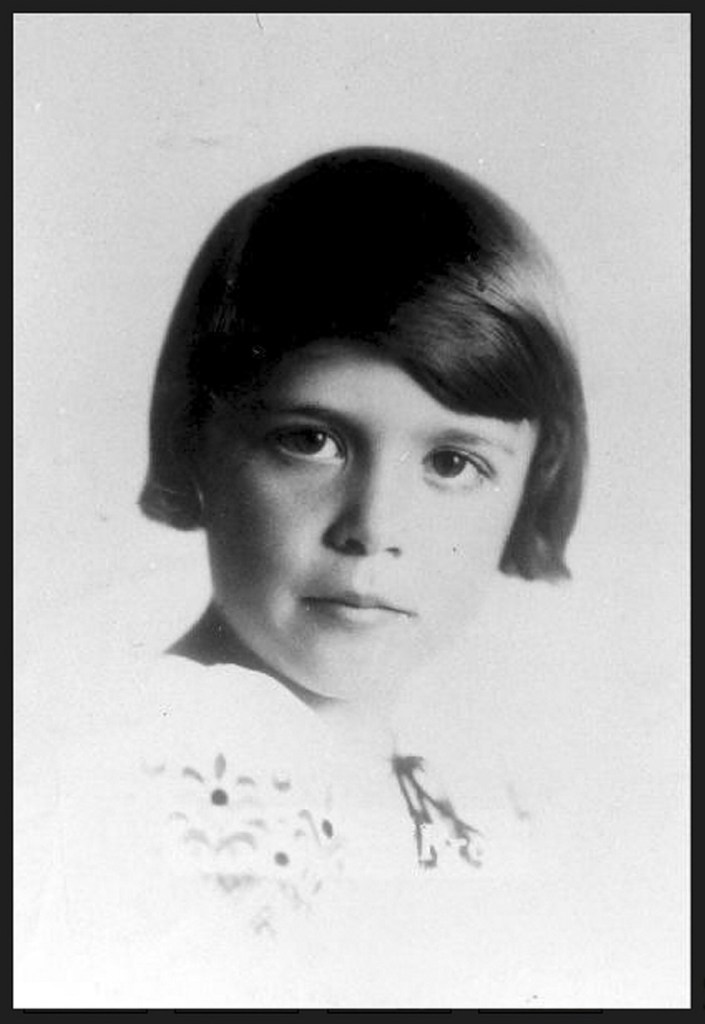

EARLY LIFE OUTSIDE NEW YORK

She was born Barbara Pierce at a hospital in Flushing, New York, on June 8, 1925, the third child of Marvin Pierce, a vice president of the McCall Corp., publisher of the leading women’s magazines of the day, and the former Pauline Robinson, daughter of an Ohio Supreme Court justice and aspiring New York socialite. The Pierces were comfortable – by the time Barbara was in high school, her father was president and chairman of McCall – and lived in the affluent suburb of Rye, New York, in a three-story, five-bedroom home with two live-in servants. But while Barbara and her three siblings were growing up, the Pierces were social climbers, with her mother in particular eager to be accepted into the higher echelons of New York society. She participated in the exclusive New York Garden Society, sought but was never invited to join the debutantes of the Junior League, ran the household into debt buying status symbols, and expected her daughters to marry up.

“My mother … often talked about ‘when her ship came in,’ she was going to do such and such or buy such and such,” Barbara recalled in her memoir, despite having a loving husband, four children and numerous friends. “Her ship had come in – she just didn’t know it. That is so sad.”

Barbara attended Rye Country Day School, took lessons at Miss Covington’s Dancing School, and watched the passenger airship Hindenburg pass overhead en route between Frankfurt and its North American terminal in Lakehurst, New Jersey. “I thought Barbara was really mean and sarcastic,” childhood friend June Biedler recalled to Vanity Fair magazine decades later, because “her mother was really a little mean to her.” She would direct her friends to not speak to one child or another in their group, “and so the rest of us would follow along and give that person a miserable time,” Biedler – a lifelong friend of Barbara’s – added. “And I don’t remember that there was ever a ‘Let’s not speak to Barbara today’ arrangement.”

For her junior year of high school, Barbara followed her older sister to Ashley Hall, a posh finishing school in Charleston, South Carolina, where she could leave the grounds only with a hat, gloves and chaperone. “I was a true square, making good marks and never breaking the rules,” she later recalled. Then, while on Christmas break at home in Rye, she attended a dance in neighboring Greenwich, Connecticut, that shaped her destiny.

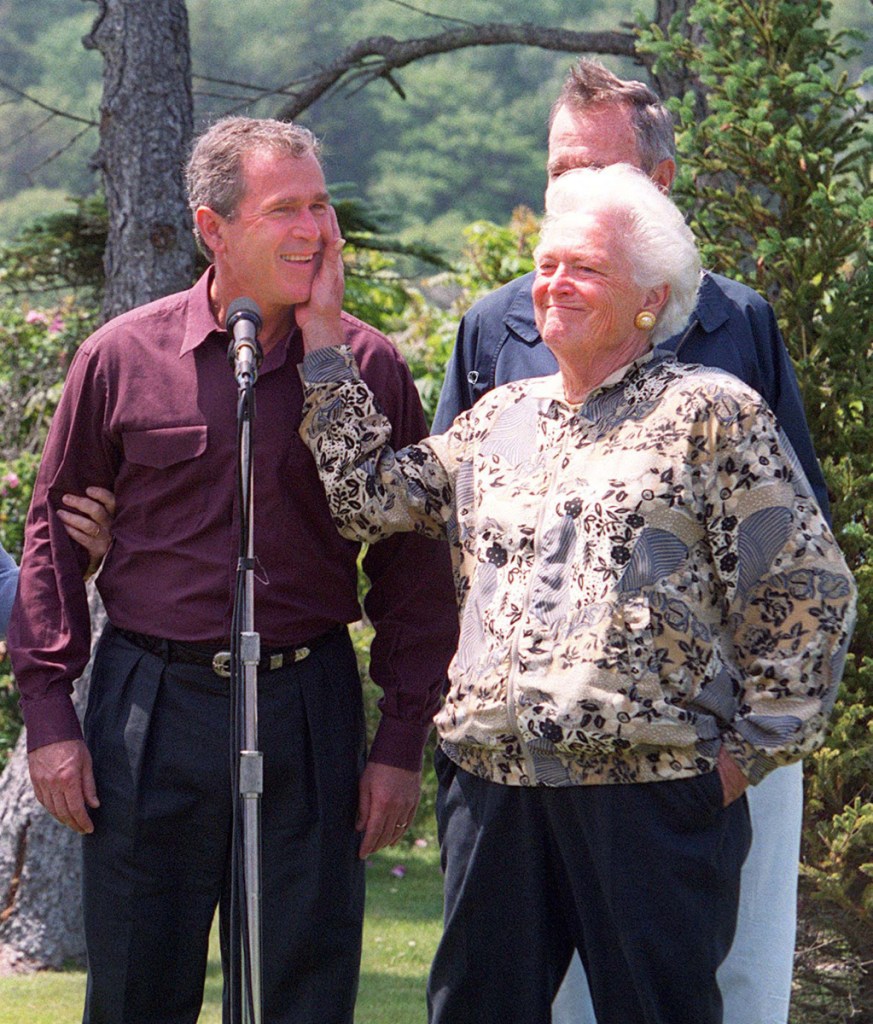

OCT. 19, 2000: Former first lady Barbara Bush smiles while campaigning for her son, the Republican presidential candidate George W. Bush, in Philadelphia. The matriarch of one of the most successful political dynasties in U.S. history, she died Tuesday in Houston at age 92.

A WARTIME ROMANCE

It was at the Round Hill Country Club, just days after the Japanese had bombed America into the Second World War, that 16-year-old Barbara and her red-and-green holiday dress drew the attention of a 17-year-old senior from Phillips Andover, the country’s most prestigious prep school. The boy – string-bean tall and self-assured in his compulsory tuxedo – asked a friend to introduce them. He was George “Poppy” Bush, native of Greenwich and son of a partner at the elite investment banking firm Brown Brothers Harriman who would later be a U.S. senator.

“He was the handsomest man you ever laid eyes on, bar none,” she later recalled. “I could hardly breathe when he was in the room.” They talked as Glen Miller and a succession of waltzes played in the background. “I’m told it was love at first sight,” their eldest son, George W. Bush, told biographer Pamela Kilian. “I think mother had heard of George Bush’s reputation from a neighboring city, and Dad saw mother at a party and fell in love with her.”

Barbara sat on her mother’s bed that night, she later recalled, telling her, ‘I’d met the nicest, cutest boy, named Poppy Bush.’ ” By the next morning, her mother had queried her extensive social network and learned he was, as Barbara later put it, “a wonderful boy who came from ‘a very nice family.’ ”

The following night, Bush swooped into Rye’s Apawamis Club, cut in on Barbara’s dance partner and asked for a date. She watched him and her brother play an informal basketball game the next day, with her entire family tagging along as spectators. They returned to Andover and Charleston, respectfully, the following day. He wrote her daily, her former roommates later told Kilian; she knitted him argyle socks.

JAN. 20, 1989: President Bush and the first lady wave to well-wishers after he was sworn in as the nation’s 41st president.

Their spring vacations overlapped by just one day; they saw “Citizen Kane” on a double-date. He kissed her on the cheek and invited her to his senior prom. Two months later he graduated, enrolled in the Navy, and shipped off for a year of basic training and flight school, where at 18 he became the nation’s youngest naval aviator. While he was on leave in the summer of 1943 before shipping off to war, George’s family invited Barbara to spend those precious days with them at Walker’s Point, where their secret engagement was sealed.

George left to fight the Japanese in the Pacific on the light carrier USS San Jacinto. Barbara went to Smith College and, by her own account, didn’t apply herself. She dropped out after her freshman year. “I was just interested in George,” she said. Back in Rye, she and her mother planned for the wedding but kept pushing the date back as his return was delayed – and spent three days in fright after learning his plane had been shot down before a second letter confirmed he had been rescued. They finally married in Rye on Jan. 6, 1945. “It was a real storybook romance,” childhood friend Rosy Clarke wryly recalled to a reporter. “They married and went to New Haven, and she worked her tail off the rest of her life.”

‘MANY LONELY, LONELY HOURS’

Actually, their lives were more frenetic than that. For the next eight months – until the war ended – they moved around the country as George’s new squadron trained: to eastern Michigan, Virginia Beach and Lewiston-Auburn, where they lived in a one-room efficiency with a Murphy bed that “smelled of other people’s cooking,” as she later described it. With peace, George started studies at Yale while Barbara kept house, “played bridge and went to movies with some of George’s more frivolous friends.” He graduated in just three years, and over the next three years they moved a half dozen more times, as George engaged in the oil business: to Odessa, Texas, and five California cities, and then to Midland, Texas. She bore six children between 1946 and 1959: George, Robin, Jeb, Neil, Marvin and Dorothy.

George traveled for long stretches of time and worked long hours when home, so Barbara spent much of her time managing the family alone. “I remember mom saying she spent so many lonely, lonely hours with us kids,” Doro later recalled. “She did it all. She brought us up.” In Odessa, they lived in a two-room apartment that shared a bath with the neighbors, a mother and daughter with “questionable occupations” and “many gentlemen callers.” They lived out of motels in Whittier and Ventura, California, and in Compton the neighbors’ small children took refuge with them while their father beat up their mother. Not until 1950 did they own their first house, in Midland, where their children would grow up.

Tragedy struck in 1953: 3-year old Robin was diagnosed with leukemia. The pediatrician, Barbara recalled, advised “tell no one, go home, forget Robin was sick, make her as comfortable as we could, love her – and let her slip away.” They instead fought for her life, flying Robin to Sloan Kettering hospital in New York City. Barbara stayed with her through seven months of painful treatment, surrounded by other parents whose children had cancer. George, who had started a new business partnership, flew back and forth from Midland. She insisted nobody cry in front of Robin, who was not to know how sick she was. At 28, Barbara had to make the decision to send the terminally ill girl to surgery to stop internal bleeding caused by the drugs she was taking, thereby buying her more time. Robin never woke up.

JAN. 21, 1989: President and the first lady pose at the White House with their children and grandchildren. Included among those photographed here are: Bill LeBlond, Doro Bush LeBlond, Neil Bush, George W. Bush and Laura Bush, Jenna Bush (hand on president’s shoulder), Barbara Bush, Noelle Bush, George P. Bush, Lauren and Pierce Bush, Mrs. Bush, Jebby Bush, the president, Ellie and Sam LeBlond and Margaret Bush.

George threw himself into his work, Barbara into the domestic life of her remaining family. Her Midland friends said she had the cleanest house, the most elaborate children’s birthday parties, and the most devoted catering to her husband’s needs. Those needs grew after they moved to Houston in 1959, where George ran his own oil company and began running for political office: county Republican chairman (he won), U.S. Senate (he lost) and Congress (which took them to Washington, D.C., in 1966). Barbara campaigned hard alongside him, visiting 200 precincts for the Harris County party chair race alone. During the Senate primaries, hate letters were pushed under their door and the postman delivered fliers claiming her father was a commie because the McCall Corp. published a magazine called Redbook.

In Washington, Barbara embraced the period role of congressional wife, socializing with her counterparts and attending receptions. “In between carpooling the children to school, I took care of the house, attended various meetings and lunches, tried to lose weight, and even took to coloring my hair,” she later recalled. In 1971 they moved to New York, where George served as President Nixon’s ambassador to the United Nations and Barbara help him entertain diplomats and volunteered at Sloan Kettering, helping adult cancer patients. Twenty months later they were back in Washington, where George, at the height of the Watergate scandal, held the unenviable job of chairman of the Republican National Committee. She summed up her D.C. life at that time in a letter to the Smith College alumnae magazine: “I play tennis, do volunteer work and admire George Bush!”

LIFE IN BEIJING AND WASHINGTON

In late 1974, President Gerald Ford appointed George as the country’s senior envoy to China, which until recently had been largely closed to America and Americans. In Beijing, with their children grown up or in U.S. boarding schools, the couple were alone together for the first time in three decades, isolated in an austere city with few social distractions and lots of secret policemen. “I loved it there,” she later said. “I had George all to myself.” They explored the city by bicycle (there were few cars there then), played tennis, entertained visitors and enjoyed each other’s company. Barbara wrote that she finally had some time for introspection. Then, just 14 months into George’s assignment, Ford asked him to return home to be director of the Central Intelligence Agency.

Sept. 29, 2011: Barbara Bush and Sen. Susan Collins laugh together after a dedication ceremony for a garden honoring Barbara Bush at the town green in Kennebunkport.

Barbara fell into a black depression. “I had a husband I adored, the world’s greatest children, more friends than I could see – and I was severely depressed,” she wrote in her memoir. “Night after night George held me weeping in his arms while I tried to explain my feelings. I almost wonder why he didn’t leave me. Sometimes the pain was so great I felt the urge to drive into a tree or an oncoming car. When that happened, I would pull over to the side of the road until I felt OK.”

In other interviews she attributed it to a variety of causes: chemical imbalance, the midlife crisis of the empty nester, the loss of access to George (who worked long hours and then couldn’t talk about what he did when he got home) and even the women’s movement, in full bloom in 1976. “Suddenly women’s lib had made me feel my life had been wasted,” she once said. Whatever the cause, it lifted by November of that year, when Ford lost the election and the Bushes returned to Houston for a quieter couple of years she described as “a second honeymoon … our quiet, relaxed time together.”

In 1980, George ran for president. There were endless receptions, luncheons, dinners and fundraisers. For the campaign, Barbara had to choose an official cause. She picked literacy, which became a lifelong passion. “I realized everything I worried about” – teen pregnancy, hunger, homelessness, drug use, crime – “would be better if more people could read, write and comprehend,” she later recalled. She was also pressured to change her image, with some family members urging her to “color my hair, change my style of dressing and, I suspect, get me to lose some weight,” she later recalled, driving her to tears. Jane Pauley of NBC opened a television interview by asking her: “People say your husband is a man of the ’80s and you are a woman of the ’40s. What do you say to that?” Barbara, though stung, declined to alter her matronly image, which instead helped her become one of her husband’s most powerful political assets. A critic, Andrew Sullivan of The New Republic magazine, called her “America’s queen mother” whose “mastery of frumpy do-goodery is, of course, modeled on the Windsors.”

George lost the Republican primary to Ronald Reagan, who then chose him as his running mate. In January 1981, George was sworn in as vice president of the United States. Months before, the couple had purchased Walker’s Point from family members to prevent it from being broken up, selling their summer home down the street and their house in Houston to finance the purchase. It became a retreat, a second home and a stage for the Bush family to stage social, political and diplomatic events over the coming decades, bringing celebrities, politicos and heads of state to Kennebunkport. The vice president’s residence at the U.S. Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C., became their primary home for the next eight years, the longest period of time they had been at one address since they’d met. But it was Walker’s Point that served as their touchstone. “For the next twelve years, it would be the perfect refuge from our high-profile lives,” she later wrote.

POPULAR FIRST LADY

They moved to the White House in 1989, after George won the presidential election, beginning a four-year term that would be most remembered for the collapse of the Soviet empire and the 1991 Gulf War. Barbara said in the first weeks she set out her personal agenda “that each day we should do something to help others,” and made frequent appearances at literacy programs, soup kitchens and with the victims of natural disasters; she secretly donated the president of the United States’ discarded clothes to a northern Virginia homeless shelter. She also enjoyed having George close by again. “If he needed a break, he’d call and say, ‘Do you want to take a spin around the South Grounds?’ or ‘Can you pop over to the Oval Office and say hello to so-and-so?’ ”

FEB. 8, 1989: During her husband’s presidency, Barbara Bush strolls on the White House South Lawn in Washington with the family dog, Millie. Early on, she set out her personal agenda: “That each day we should do something to help others.”

As first lady, Barbara steadfastly stayed out of policy debates, at least in public, but she had plenty of private views, some of which conflicted with her husband’s. In 1988, she visited a Washington nonprofit that cared for babies with AIDS, and was photographed holding one at a time when many Americans still feared contact with anyone suffering from the disease and her husband was accused of ignoring the crisis. Asked whether she supported a ban on assault weapons, she said she did, assuming incorrectly that they were already illegal. She denounced the inclusion of an anti-abortion plank in the Republican Party platform. Aides credited her for showing compassion in areas he seemed aloof from – “poverty, pain, and degradation, basically,” as one told Vanity Fair in 1992.

In private, her caustic and judgmental side kept staff, aides and even friends on their toes. “She really takes a bead on someone and, for good or for bad, you’re in that box; you’re pigeonholed,” one longtime associate told Vanity Fair. “She’s a good person, she talks about AIDS and stuff,” a former aide added. “But she’s not this nice person.” Sometimes this side would slip out, as in 1984, when she denounced Democratic vice presidential candidate Geraldine Ferraro as “I can’t say it, but it rhymes with ‘rich.’ ”

By the end of his term, George’s popularity faltered, as voters judged him out of touch on domestic issues and the economy. They entered the 1992 re-election campaign with Barbara’s approval rating 40 to 50 points higher than his, and in his stump speech George took to beginning sentences with the words “Barbara and I.” Campaign staff members called her their greatest asset. “Nobody is jealous of me,” Barbara explained when asked about her relative popularity compared with her husband and his Democratic rival’s wife, a lawyer named Hillary Clinton. “I mean, look at me. Who would be? It’s easy to like me. … But (George) has to say no to people because he has to do what is right for the country, and that’s hard.”

George’s loss hit Barbara hard, especially as she had little respect for Bill Clinton. “The American people would never vote for him,” she recalls thinking. “I wrote him off from the start.” In her memoirs, she ascribed the loss to Americans’ desire for change after 12 years of Republican presidencies and a bias in the media, then dominated by baby boomers who supposedly identified with the Clintons. They moved back to Houston, where she remembered getting reacquainted with shopping, cooking and driving for the first time in more than two decades.

Sept. 3, 2003: Barbara Bush reads to a group of young patients in the Inpatient Unit at the Portland children’s hospital that bears her name. The former first lady was visiting to take part in the summer reading program and to help announce a large addition to the children’s hospital.

But the presidency was not leaving her family behind. Eight years later, eldest son George W. Bush was elected president, assisted by a lifetime of contacts and associates Barbara had carefully assembled, first as a Christmas card list. While the younger President Bush preferred his Crawford, Texas, ranch, Walker’s Point still became a presidential venue again, with French President Jacques Chirac and Russian President Vladimir Putin visiting the compound. Many political observers expected another of her sons, Jeb Bush, would win the 2016 Republican presidential nomination, but he was routed by Donald Trump and left the race in February 2016, tweeting only two words: “Sorry mom.”

LATER YEARS IN KENNEBUNKPORT

Throughout their post-presidential lives, Barbara and George continued summering at Walker’s Point, maintaining friendships in Kennebunkport and donating their time and resources to local causes, including the Maine Literacy Volunteers, the Barbara Bush Children’s Hospital at Maine Medical Center, and the University of New England in Biddeford, which is home to the George and Barbara Bush Center.

In the fall of 2017, the Bushes’ lives were briefly shaken when 10 women came forward alleging George had groped their buttocks, nine of them while posing with him for photographs. The alleged incidents, which spanned a 26-year period between 1992 and 2016, included an alleged victim who was 16 at the time and another who was a Republican candidate for the Maine Senate. Many of them occurred with Barbara present, and several accusers described her lightly admonishing her husband. Through a spokesman, Bush apologized for some of the incidents and didn’t deny any of them. “He has patted women’s rears in what he intended to be a good-natured manner,” the spokesman, Jim McGrath, said in a statement at the time.

In later years, George used a wheelchair because of a Parkinson’s-like disease, and family members said Barbara dedicated herself to making his life more enjoyable, facilitating outings and visits with friends and family. Daughter Doro likened her to the protagonist of one of her mother’s favorite books, “Miss Rumphius,” by Maine author Barbara Cooney, a woman who spent her life beautifying the world with lupine plantings. “While my mother may not have spread actual flower seeds throughout the world, she certainly makes it a more colorful and beautiful place,” Doro wrote in 2015. “She is our very own Miss Rumphius.”

Colin Woodard can be contacted at:

cwoodard@pressherald.com

CORRECTION: This story was updated at 10:15 a.m. Wednesday, April 18, 2018 to correction the date Jeb Bush left the 2016 presidential race.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story