Deep in the western Maine woods, where the snowpack is still 4 feet deep, 5 miles of tubing forms a web between the maple trees, waiting for the season’s first major sap run. Marie Harnois, manager of Passamaquoddy Maple, says that probably won’t happen until the end of March or the beginning of April, but when it does she and her co-workers plan to turn that sap into 3,000 gallons of maple syrup.

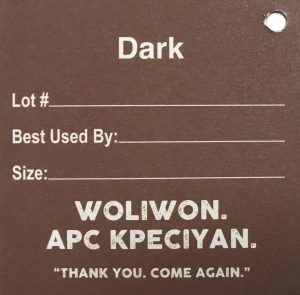

The sap will be boiled inside a brand new sugarhouse, powered by generators and frequented by a hungry fox, that’s set 9 miles back into the forest of Prentiss Township. The syrup will then be brought by the barrel full to a small bottling facility in Moose River, just up the road from Jackman. Each bottle will be tagged with a message from the Passamaquoddy tribe, in their own language: Woliwon. Apc kpeciyan.

That means “Thank you. Come again.”

Harnois is proud of the certified organic syrup her tribe makes here. She has the staff write a handwritten note on each receipt that goes out with a bottle of syrup, again saying “Woliwon.”

“To me, it makes it more personal,” she said. “We make some excellent syrups here in Maine, but we’re also sharing where it’s coming from.”

The Passamaquoddys bought the sugarbush after the Maine Indian Land Claim Settlement Act of 1980, which provided Maine tribes with $81.5 million in reparation for lands that had been taken from them by the United States. Passamaquoddy Maple collected its first sap in 2014, and five years in, the business is growing steadily with the help of a couple of federal grants. Each year so far, the tribe has reinvested sales revenue back into the company as required by the grants. They expect this season will be profitable, with the number of taps and demand for the product increasing, and hope one day to become one of Maine’s largest maple syrup producers, said Joseph Socobasin, who was chief of the tribe’s Indian Township reservation when the project got underway. He said the tribe is counting on the business to put a small dent in the tribe’s high unemployment rate, which hovers around 50 percent.

“When these grants are over and done with, I don’t want to have to depend on a grant from year to year,” he said. “I want this thing to grow and generate enough revenue that we don’t need any help from anywhere else. It’s on its way.”

The Passamaquoddys’ ancestral homeland historically ranged from midcoast Maine up through Nova Scotia, where the tribe took advantage of fish from the sea and game from the forest to feed themselves. They drank maple sap fresh from the tree as a tonic, and also boiled it to make syrup and sugar, according to J. Donald Cyr, who teaches history and art at the University of Maine-Presque Isle and is an expert on Acadian culture. The tribe taught the French how to tap and use the sap, he said.

Today the tribe has 3,600 members who live in three self-governing communities at Indian Township, Pleasant Point and St. Andrews, New Brunswick.

The 60,000 acres they purchased in the early 1980s in western Maine – half on the north side of U.S. Route 201 in Prentiss Township, the other half on the south side – is former paper company land where everything had been cut but the hardwoods, leaving large clearcuts behind.

“The paper companies took all of the wood that had any value, and they left the hardwood,” Socobasin said, “which was good for us because there’s a lot of sugar maple in the area. We always had the idea that someday we’d like to tap those trees, make maple syrup and start a small business that could employ maybe eight to 10 people.”

A three-year, $1.5 million federal grant jump-started the project. A second grant, which runs for five years, must be matched by more than $500,000 in tribal funds. To pay that share, the tribe set aside $500,000 from the sale of its carbon credits, which are credits received by businesses and organizations for removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. They are sold through a California state government program that offsets carbon emissions generated by polluters beyond what they are legally allowed to emit; the system is known as cap and trade.

Climate Action Reserve, a national environmental nonprofit organization, in 2016 gave the Passamaquoddy tribe a “Project Developer of the Year” award for generating 3.8 million carbon offset credits through its sustainable forest management project (remember, trees absorb carbon dioxide). That project, which also started in 2014, encompasses 90,000 acres of tribal land, including some of the sugarbush territory.

A $250,000 grant from the Northern Border Regional Commission built and equipped the sugarhouse. A former state forestry building has been converted into a bottling facility, with extra room for staff and storage.

Six employees, all members of the tribe, have been hired to run the maple syrup operation, plus six tribal tappers who work seasonally. Four of the six full-time employees are cross trained in bottling, packing and sales, Harnois said. The other two work in the field, watching over the tap lines and working in the sugarhouse. They share the woods with moose, deer, coyotes and wild turkeys. Their first year tapping, they ran across a bear den. They regularly see lynx tracks. And they have bonded with a fox they named Swiper, after a character on the “Dora the Explorer” TV show, because, Harnois said, “she will steal your lunch if you leave it out.”

As staffing goes, it’s not a huge operation, but Harnois hopes the payroll will grow as the business grows. She notes that some employees are discovering they are good at sales and marketing, and all are learning valuable skills that they could transfer to another job. “This experience and this education they’re getting here, they could take to another place if they so choose later on, or (use it) in their own businesses,” she said.

The syrup is marketed in traditional maple syrup bottles with maple leaves, moose and other designs in relief. Harnois said some people buy the syrup (golden, amber, dark or very dark) because they want to support a tribal business, “but they’ll come back for the taste. We have to have a good product in order to be able to do that.”

Passamaquoddy Maple has tapped 12,000 trees so far this year, and hopes to hit the 15,000 mark. The long-term goal is 70,000 taps, Socobasin said.

“Once that’s done we’ll be moving to another township,” he said. “We would have to build another sugarhouse to run those lines and tap those trees, so we’re looking for another massive expansion. A lot of it would be wholesale, but by doing that, we can create more job opportunities for our people who would be willing to come up here and work so we can continue growing this company. We have the potential, the trees, to be one of the biggest producers in the state.”

The tribe’s foresters estimate 200,000 tappable trees are on tribal land. Socobasin said they’ve been advised by similar syrup businesses that they can expect to earn $350,000 to $400,000 for every 25,000 taps, but those numbers can change depending on the fluctuating price of maple syrup.

Harnois says the tribe ships its syrup all over the United States, including in Florida, Massachusetts and Tennessee, and they are starting to sell the syrup internationally. They also sell syrup on their website, passamaquoddymaple.com, at fairs and festivals, and at their retail shop in Moose River, where a quart of syrup costs $18.95. A quick online search shows other Maine sellers charging $20-$22 per quart.

Any money made from maple sugaring will go back to the tribe, which then decides where to invest the profits, Socobasin said.

Harnois and Socobasin are well aware that climate change could alter the plans they have for the syrup business, if warming temperatures push maple trees farther north. That’s something the tribe’s foresters are monitoring and learning more about as the project develops, they said.

“Where our stand is located, the elevation is 1,500 feet as well, so there’s a difference in temperature just from driving from town out into where our stand is,” Socobasin said. “Sometimes it can be 10 degrees. So hopefully they’re not impacted in quite the same way as they may be down in Portland, but it is definitely something that is on our radar.”

Long-term sustainability is the most important aspect of the project, he said.

“We want a healthy stand,” Harnois said. “That’s where all our money is, but it’s also who we are as a people.”

Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at:

mgoad@pressherald.com

Twitter: MeredithGoad

Comments are no longer available on this story