BOSTON — Volunteer coordinators, take heart. More than 2,000 people around the world raised their hands when the Boston Public Library put out a call for help to transcribe its extensive, unsearchable and largely illegible collection of old anti-slavery documents.

Through a website on the crowdsourcing research portal Zooniverse, the library recruited an army to make 12,000 pieces of correspondence written by some of the most prominent New England abolitionists of the era accessible to researchers and the general public.

“The collection is an amazing glimpse into how a motivated community of activists can change the course of history,” said Tom Blake, the library’s content discovery manager.

The goal of the project launched a month ago is to make the documents searchable and, therefore, easier to read and research. So why give the task to volunteers?

For two reasons, Blake said. First of all, using the library’s current staff, or hiring someone to transcribe the letters, would have been too time-consuming and expensive.

But the other reason was to engage people with the library.

“It’s a way for the public to become part of the library – not just consumers of library materials but actual creators and participants,” he said.

More than 2,200 people have already signed up to help, and not just from New England.

David Kaminski, a high school English teacher from Nyack, New York, has been involved in several similar transcription projects, but said the Boston project is special.

“This project is particularly interesting because these people were involved in something so powerful and important,” he said. “You can really hear their voices, the emotions of the writers coming through.”

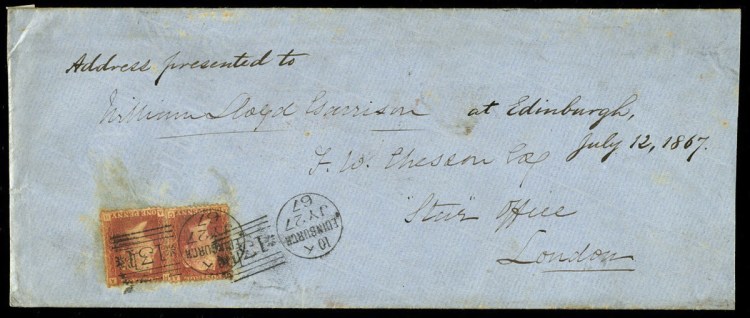

Much of the collection was donated to the library in the late 1890s by the family of prominent abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. His donation, in turn, inspired others closely involved in the movement to donate their correspondence. The material dates from 1832 until just after the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation.

The letters often express the fears and hopes of the movement.

“I fear with you that we are to see the free colored people subjected to a cruel persecution, to make them disposed to emigrate,” Arthur Tappan, of New York, wrote to Garrison in a letter dated Jan. 21, 1832. “We have reason to fear as a people the vengeance of Heaven for the sins (we are) guilty of to the Indians and to the (children) of Africa.”

Transcribing the documents isn’t easy. The handwritten letters are sometimes difficult to read and often use archaic language.

“At that time, a lot of people had really band handwriting,” said Kathy Griffin, an archivist with the Massachusetts Historical Society who is one of the volunteers. “It’s just messy.”

To ensure the transcriptions are as accurate as possible, three people must transcribe a text in exactly the same way before it is considered finished.

“So far, we’re very happy with the level of accuracy,” Blake said.

Although the project could take two years to complete, the goal is to periodically post the completed transcriptions along with images of the original documents.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story