Frances Hynes is an established New York City-based artist whose work is now on view at Elizabeth Moss Galleries in Falmouth, a gallery that has represented her for years. Since her first solo show in New York in 1974, Hynes has had dozens of solo exhibitions in galleries and museums, including the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, MoMA PS1 in New York and the Ogunquit Museum of American Art, where she had a 10-year retrospective. Hynes’ work is held in major collections across the country, locally including the Colby College Museum of Art, Bates College Museum of Art and Portland Museum of Art.

“Marking Time: Of Land and Sea” is a show of paintings largely dedicated to an ethereal sense of landscape, seascape or even nautical figuration. Yet the fundamental effect of this body of work is abstraction. It is Hynes’ meditatively slow painterly rhythms that set the pace of the viewer’s experience.

Hynes builds up thick and layered surfaces of densely textured paint. Even when her brush meanders, such as in the echoing waves of “After Labor Day,” the energy of the rhythms ultimately is overrun by the dense presence of paint on the surface. In this case, the waves are represented abstractly on a flat painted surface; they move down like text on a page – in even lines that we read left to right. But because it is a painting, when we are finished dropping with the movements, we lift our eyes to the top left to restart. There, the atmospheric opalescent pinks swallow up the lolling white strokes of the waves. The result might use spatial logic, but because the titanium white is the most opaque pigment, the focus is on the painted surface. This shift, from light to pigment, is the shift from representational painting to abstraction.

‘Island Place (Monhegan),’ 2008, oil on canvas

In “Marking Time,” the presence of abstraction dominates from the start, and it is only with a longer look that the logic of representational painting comes into view. One painting features a brown form directly under a pink atmospheric center. It reads initially as abstract, but the brown form comes into focus on as an old wooden ship. The form is so low, however, the scene defies nautical logic, though it may be explained by the title: “On Land.” For many Mainers, the image that might come to mind is the Hesper or the Luther Little, two ships that had been abandoned in Wiscasset until they were ultimately demolished in 1998.

“After Labor Day,” 2011, 37 x 48 inches, oil on canvas.

Hynes’ willingness to shift modes, from landscape to abstraction, from abstraction to nautical to landscape and so on is both what makes her work so challenging and so rewarding. This is, after all, the fundamental function of painting. At one point, it is a material object with a physical presence. At another point, it is representative of something, even if that something is a conceptual practice or the cultural act of painting. Hynes is old school. Her work is built patiently. Visually, it develops slowly. It rewards patience. Its modernist conceptualism arrives at a glacial pace, delivering with it a spiritual meditativeness.

“On Land,” 2017, 30 x 40 inches, oil on linen.

If “Island Place, Monhegan” were not in the context of this conversation, but merely seen, it could hardly be recognized as a landscape or seascape. As it is, it’s impossible to tell if you’re looking at a sky above a horizon line or down at the ocean beyond the edge of the land. It may be that Hynes is having it both ways with a reference to Monet’s late waterlily paintings: the upper three-quarters of the painting is a field of pink puffs among a cerulean field floated on a solidly built-up white (as in opaque) surface.

What Monet did with his late paintings (besides ultimately inspiring Abstract Expressionism) was to look down and paint the sky reflected in his garden pond. So, yes, it became several things at once: a Japanese-style landscape looking down below a horizon line, a view up to the sky and a highly abstract painting. Hynes’ dedication to painting in the mode of Monet is apparent with her built up textures, which are only made possible by pulling the brush over and over the surface. Her rhythms, however, are closer to the abstractions of Philip Guston (1913-1980) with their pulsing brush strokes. Of course, Guston’s abstractions ultimately hail back to Monet as well.

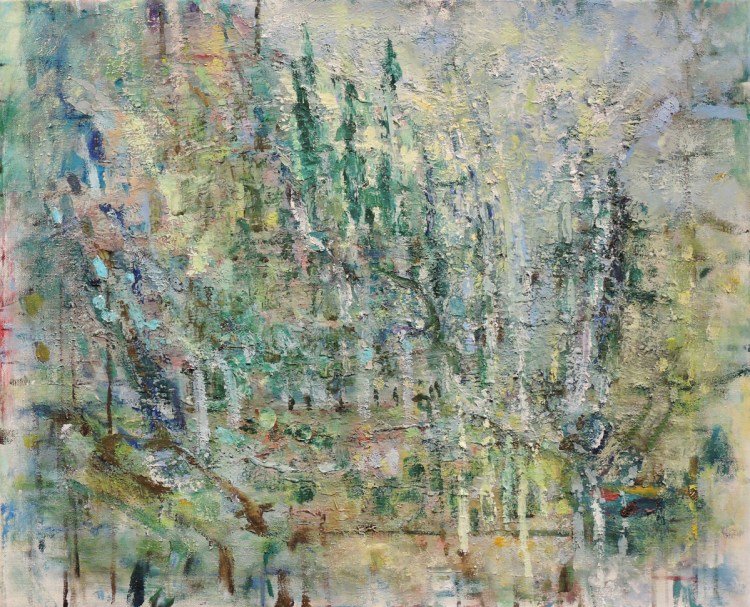

“Aerial,” 2016, 20 x 30 inches, oil on linen.

Hynes is deliberate with her movement between vertical and horizontal modes. “Aerial” and “In the Mountains” are similarly structured on their surfaces: the top right corners open with a bit of airy light blue while the rest of the surface is dominated by a flickering green. The difference is that one is a landscape – a vertical view, like through a window – while the other is a view down onto the water – horizontal, like at a map on a table. In a sense, this is the basic truth of spatial painting: We look at a flat vertical object and read in it horizontal spatial depth. Add to this Hynes’ dedication to mark-making and the extraordinary surface textures of the paint, and we can safely say Hynes is an old-school American High Modernist, through and through.

“Marking Time” is a fitting show for Maine. Hynes’ comparison of the modes of seascape and landscape has been a fundamental dialogue of Maine art through the ages (from Homer to fellow Elizabeth Moss artist Richard Keen). Her trust in the sophistication of her sensibilities is well-earned, and it leads to one of the strongest shows that Moss has mounted in quite some time.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story