Lyme disease and anaplasmosis soared to record highs in Maine last year, with experts saying the relatively warm fall probably contributed to the increase in tick-borne illnesses.

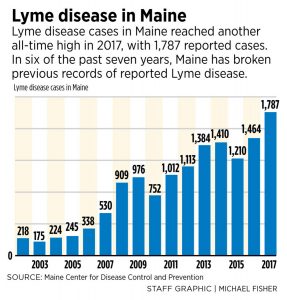

Except for a slight downturn in 2015, reported cases of Lyme disease have now broken records in Maine every year since 2011.

There were 1,787 positive tests for Lyme in 2017, a 22 percent increase over the 1,464 Lyme cases in 2016, according to statistics compiled by the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention. There were about 1,000 cases annually early this decade and a few hundred a year in the mid-2000s, Maine CDC data show.

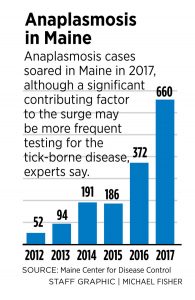

Meanwhile, anaplasmosis cases jumped 78 percent in 2017, to 662 from 372 in 2016. Five years ago, there were fewer than 100 cases of infection annually from the anaplasmosis bacteria.

Lyme and anaplasmosis have similar flu-like symptoms, including fever, chills, headaches, fatigue and joint pain, but anaplasmosis symptoms tend to be more severe and are more likely to result in hospitalization.

TESTING TICK SURVIVABILITY

If caught early, both diseases can be treated effectively with antibiotics. Because many cases are not reported, the actual numbers of Lyme and anaplasmosis cases are much higher than the official reports from the government, health experts say.

Susan Elias, a disease ecologist at Maine Medical Center Research Institute, said it’s difficult to say what could have caused the increase in cases last year, but more awareness of tick-borne diseases by primary care physicians, better reporting of positive test results to the Maine CDC and a warm autumn could be reasons why 2017 was a banner year for Lyme disease.

Susan Elias, a disease ecologist at Maine Medical Center Research Institute, said it’s difficult to say what could have caused the increase in cases last year, but more awareness of tick-borne diseases by primary care physicians, better reporting of positive test results to the Maine CDC and a warm autumn could be reasons why 2017 was a banner year for Lyme disease.

“A warm fall might extend the questing season of nymphal and adult ticks,” Elias said of the period when ticks crawl up blades of grass or perch on the edges of leaves in a bid to latch onto a host. “Ticks are alive and well when temperatures are less than 50 degrees Fahrenheit, but they are much less active and less likely to find a host for a blood meal.”

Elias said that with a warm fall, people are also more likely to be outdoors and exposed to active deer ticks, which could contribute to the increasing numbers of Lyme cases.

“Anytime you compress the winter and the number of cold months, that’s good for the ticks,” Elias said.

The research institute is studying the effects of climate change on the range of the arachnid and how it could be contributing to the spread of Lyme disease. The center is in the third year of studying how ticks survive the winter, and this is the first winter with extended bitter-cold temperatures, which will be a good test of tick survivability, Elias said. Deer ticks have increased their range in Maine over the past 20-30 years, and are appearing much farther north, especially along the coast.

Elias said the jump in anaplasmosis cases could have been significantly affected by improved testing methods. She said several years ago when a patient was suspected of having Lyme disease, doctors sent away blood samples and only tested for Lyme. Now they send for a “tick panel” that routinely tests for Lyme, anaplasmosis, babesiosis and possibly other tick-borne diseases.

‘TICKS ARE EVER MORE PERVASIVE’

However, researchers are also finding that ticks are now more likely to carry both Lyme and anaplasmosis, especially in southern Maine.

Dr. Philip Baker, executive director of the Connecticut-based American Lyme Disease Foundation, said Mainers live “close to nature,” which may be one factor in the rise of tick-borne diseases.

Dr. Philip Baker, executive director of the Connecticut-based American Lyme Disease Foundation, said Mainers live “close to nature,” which may be one factor in the rise of tick-borne diseases.

“I don’t think it’s any one thing. It’s a combination of a number of things,” Baker said. “People are building homes in wooded areas. A bigger acorn crop could be a reason, because more acorns mean there’s more mice and other rodents for the ticks to attach to, which can spread Lyme disease.”

Angela Coulombe of Saco, a Lyme disease activist who contracted the disease several years ago, said that although it’s frustrating that cases are still climbing, the increase is leading to greater awareness of the problem, which means more resources may be devoted to the public health issue. People can do simple things to prevent themselves from contracting Lyme disease, such as doing frequent “tick checks,” having a buffer between wooded areas and homes, wearing proper clothing when going into the woods and putting on repellent.

“Ticks are ever more pervasive, and we are more likely to be exposed to them,” Coulombe said. “We have made huge leaps in awareness over the past 10 years, but there’s still so many physicians who aren’t aware of the proper treatments.”

Joe Lawlor can be contacted at 791-6376 or at:

jlawlor@pressherald.com

Twitter: joelawlorph

Comments are no longer available on this story