Portland isn’t the only Maine community facing costly projects to separate combined sewer-stormwater systems.

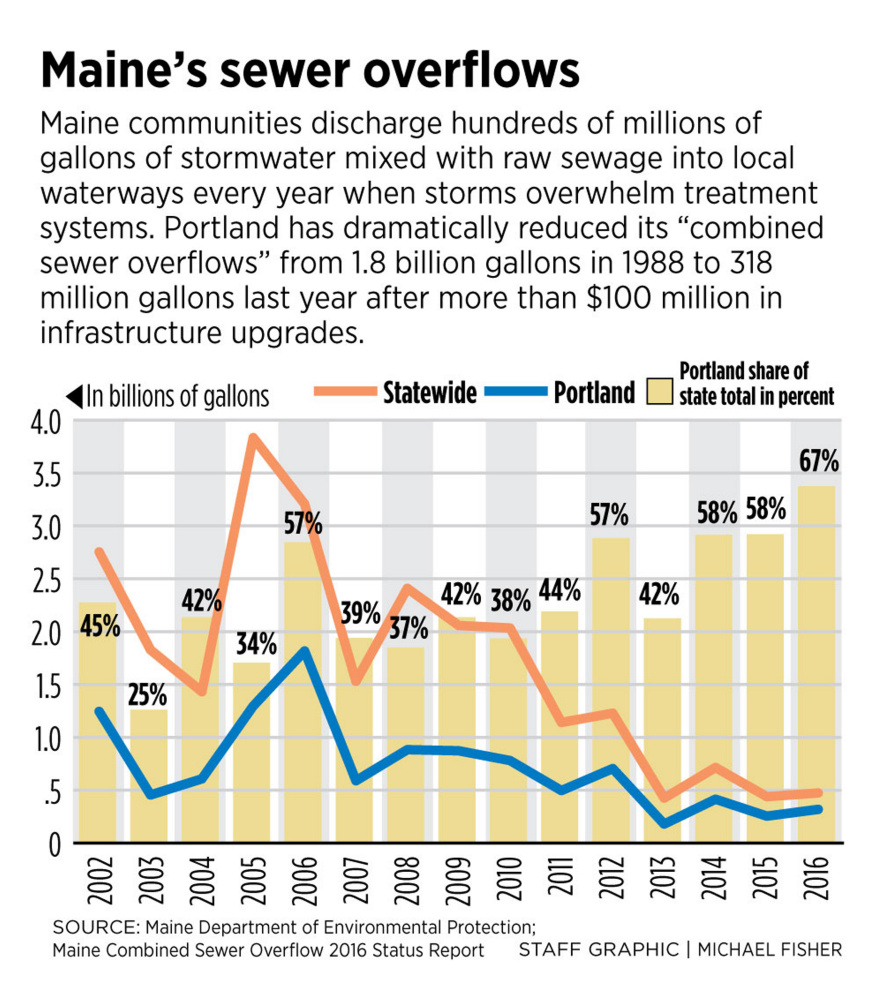

In 1989, 60 cities and towns across the state dumped an estimated 6.2 billion gallons of stormwater mixed with raw sewage into local waterways, with Portland accounting for roughly one-third of those discharges.

By 2016, the number of municipalities with combined sewer overflow systems, or CSOs, had dropped from 60 to 31. Portland’s share of overflow discharges, meanwhile, had risen to two-thirds of the statewide total of 474 million gallons – a reflection of the cost and complexity of separating century-old combined sewer-stormwater systems underneath the heart of Maine’s largest city.

“They are making progress, but it is slower because construction in Portland is harder than in other cities,” said Mike Riley, coordinator of the Maine Department of Environmental Protection’s CSO program.

According to the DEP, 13 communities ranging from Milo to Yarmouth had successfully eliminated overflow discharges by 2016. Several more, such as South Portland, are approaching that point after years of often costly system upgrades.

In 2016, South Portland had the eighth-largest amount of overflow discharges in the state, with 6 million gallons. But that figure represents a 99 percent reduction from the 450 million gallons discharged into Portland Harbor or Casco Bay in 1989, according to the DEP.

Riley called South Portland “the poster child” for overflow reductions. The estimated $39.2 million South Portland has spent on overflow-related projects comes out to $1,569.39 per resident, which places the city about halfway down the list of per capita expenditures, DEP data show.

Patrick Cloutier, director of the South Portland Water Resources Protection Department, said the city has reduced the number of overflow discharge points from 28 to six but the final batch is more difficult. Cloutier said the City Council and local residents have been very supportive as South Portland works toward its official goal of having no overflow discharges for storms of up to 2 inches of rain, although total elimination of overflow pollution is the end goal.

“We’ve been very fortunate,” Cloutier said. “South Portland is pretty progressive regarding their views of the environment.”

The city with the largest per capita overflow expenditure was Calais, at $5,518. That money has allowed Calais to separate 98 percent of its combined sewer-stormwater infrastructure as of 2016, although the small city in Washington County still reported 4.6 million gallons in overflow discharges that year.

In 1988, the city of Brewer – population roughly 9,000 – ranked only behind much-larger Portland in terms of total overflow discharges. That year, an estimated 750 million gallons of stormwater mixed with raw sewage flowed from overflow pipes directly into the Penobscot River and its tributaries. But after 25 years of disruptions tied to infrastructure upgrades, Brewer had reduced those discharges into the Penobscot – home to numerous endangered or threatened species – to just 465,000 gallons in 2015 and 87,374 gallons last year, or a fraction of 1 percent of the 1988 flow levels.

“It’s not easy to have streets torn up everywhere for 20 years, but ultimately they made those sacrifices and are better off for it now,” the DEP’s Riley said.

While Brewer set a goal of separating all of its stormwater and sewer infrastructure, most of Maine’s larger cities opted for “targeted separation” that addresses the areas causing the biggest discharge concerns.

In Portland, it would have cost an estimated $500 million to fully separate all overflow infrastructure and caused seemingly nonstop traffic headaches downtown in the process. Instead, the city is focusing on the areas where it can get the most bang for its 250 million bucks, most notably the combined lines and overflow discharge points into Back Cove and the harbor along Commercial Street.

But Portland and other communities are increasingly exploring more passive ways to reduce overflow discharges without tearing up streets. For instance, the city has installed “rain gardens” in numerous spots and is using permeable pavers in some parking lots to allow more water to filter into the ground rather than flow into storm drains.

“If I can put that water into a rain garden so it doesn’t (infiltrate) the system, that’s huge,” said Brad Roland, the city’s stormwater engineer.

Riley believes Maine has made significant progress over the past 30 years addressing its legacy overflow discharge problems.

“We have had some real success stories, but we certainly have a number of challenges, too,” Riley said. “Some communities are behind others, but we just have to continue working with those communities.”

Kevin Miller can be contacted at 791-6312 or at:

Twitter: KevinMillerPPH

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story