ORONO — Gabriel Frey separates each layer of ash as if he is peeling an onion. He removes one thin layer after another until he reduces what had been a formidable stick of wood into a small bundle of flexible ribbons. He then narrows each with a hand-held, handmade splitting tool, and weaves the strips seamlessly into one of his ash baskets.

Frey, a Passamaquoddy who works in the basement studio of his Orono home, is busy preparing baskets for seasonal markets in Maine and elsewhere, including several for the Smithsonian Institution, which commissioned him to make baskets for its New York gift shop. He is among a large group of American Indian artists from Maine whose reputations are growing nationally, enhanced by their successes at juried American Indian art markets across the country. For six years, Wabanaki artists from Maine have won top honors at the Santa Fe Indian Market in New Mexico, the largest indigenous art fair in the world. Frey was among three Wabanaki artists to win ribbons at the most recent market in August, snagging a first-place award and an honorable mention.

Next spring, Frey will show his work closer to home, as the Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor hosts a three-day juried American Indian art market May 18-20 in downtown Bar Harbor, creating more exposure for Indian art and artists from Maine and the Northeast. Maine is home to many small American Indian festivals and fairs – the Maine Indian Basketmakers Holiday Market held last weekend at the Hudson Museum at the University of Maine is a good example – but a large-scale juried art show that encompasses a range of arts and attracts artists and audiences from across North America is unusual if not unprecedented in the Northeast, said Abbe Museum President and Chief Executive Officer Cinnamon Catlin-Legutko. Nearly all the major American Indian art fairs are in the Southwest or Northern Plains.

A ‘BIG DEAL FOR MAINE’

“It’s a really big deal for Maine and New England,” she said. “Wabanaki art forms have been thriving and innovating for centuries, but it’s only been in the past decade or so that Wabanaki artists have been getting global recognition. They have to leave their homeland to get the praise they deserve. We want to change that.”

Wabanaki refers to the regional tribes of Maine, including the Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, Abenaki, Maliseet and Micmac. Wabanaki artists Jeremy Frey, Theresa Secord, Sarah Sockbeson, Geo Neptune, Emma Soctomah and the late David Moses Bridges have won top prizes at Santa Fe and the Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair and Market in Phoenix, the other major market in the Southwest.

Dawn Spears, a Narragansett and Choctaw Indian who is working with Abbe to produce the Bar Harbor market, said the museum is capitalizing on the convergence of a void in regional American Indian art markets and heightened interest in Native American arts overall and Wabanaki art in particular. Connecticut hosted an American Indian art market a few years ago, but there has been nothing since and nothing on the scale the Abbe is organizing, she said.

The museum, which specializes in the history and contemporary culture of the Wabanaki Nation, expects about 100 artists will participate, with about 25 percent of them representing Maine tribes. “For whatever reason, the Northeast has always been underrepresented,” said Spears, executive director of the Rhode Island-based Northeast Indigenous Arts Alliance. “The Northeast needs a market that will bring people from the outside here and really showcase the art that is happening here. The Abbe is in a position to fill that void and remind people there are still Indians here and still creating amazing work. This is an opportunity to shout that from the rooftops.”

The Northeast Indigenous Arts Alliance supports American Indian artists by sharing resources and opportunities, addressing needs and seeking ways to increase the visibility of Native American artists in the region. The Abbe market will showcase “homegrown” talent, she said, while showing their work alongside artists representing tribes from across North America.

INCREASING EXPOSURE, SALES

Catlin-Legutko estimates the May market will generate about $250,000 for the local economy through lodging, meals and services, with attendance likely in the tens of the thousands. The goal, she said, is to highlight the works of Wabanaki artists while creating more economic opportunities for them to practice their art full time by increasing their exposure and sales. In addition to the art market, the May event will include an indigenous film festival and fashion show. As the event grows in the future, Catlin-Legutko envisions the market expanding to include art competitions and Native American foods.

She wants Bar Harbor to become the “Santa Fe of the Northeast. This is our moment and our opportunity,” she said. “In a perfect world, we could take over the town. That is not unrealistic, though it could take a few years.”

By comparison, the Sante Fe market draws more than 1,000 artists and 150,000 visitors, and has been around nearly 100 years.

Frey, 37, was among seven Wabanaki artists showing at Santa Fe this year. He won a first-place prize and honorable mention in the twined-wicker category of non-Southwest basketry, adding to an honorable mention that he won in 2016, his first year at Santa Fe. Frey comes from a long line of Passamaquoddy basketmakers and learned to make baskets as a teenager working alongside his grandfather. He sees his work as a continuation of a family legacy. “Everything that I do is an adaptation of what my grandfather did,” Frey said.

Frey’s baskets are distinguished for their lack of glue and lack of nails, and his use of leather. Everything is held together by rugged, tight weaves. He processes all of his ash, beginning with the harvesting of the trees. He dyes his ash naturally and makes most of his tools.

He took nine baskets with him to Santa Fe this past spring and sold all of them. He is thrilled that a market is coming to Maine, if only so other Maine-based American Indian makers can show their work in context with their contemporaries. Until he traveled to the Southwest, Frey didn’t fully recognize how skilled Maine makers were and how well they measured in comparison with others. “I think it’s fabulous that our traditional art forms are starting to get more recognition,” he said.

BUILDING ON TRADITION

The Abbe Museum Indian Market will showcase much more than brown ash and sweetgrass basketmakers. There will be birch-bark artists, carvers, beadworkers and purveyors of other art forms. Among the artists who will travel to Maine is Katrina Mitten, a contemporary designer and beadworker from Indiana. Maine basketmaker Theresa Secord wore a vest made by Mitten when the National Endowment for the Arts honored Secord as a National Heritage Fellow in 2016.

Like many other contemporary Native American artists, Mitten builds on the traditions of her elders, but doesn’t copy them. She has been recognized for her innovations as a designer and is looking forward to coming to Maine so she can expand her market. “There just aren’t many Indian art markets east of the Mississippi,” she said. “I like to do new markets, and I have never been to Bar Harbor. This seemed like a perfect opportunity.”

Loren Aragon, a fashion designer from Arizona, said he signed up for Bar Harbor “for a change of scenery. I’ve been to New York, and I loved that area. I want to see more of that part of the country. I am trying to get more exposure and engage a different audience.”

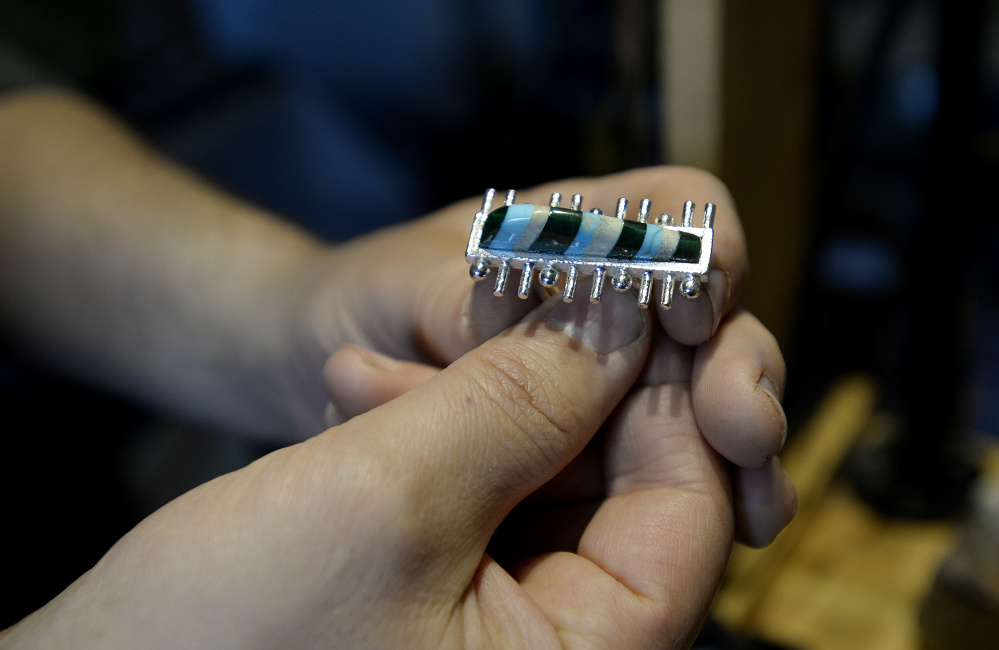

Jason Brown and Donna Decontie-Brown are Penobscot fashion designers and jewelry makers from Bangor. They make handcrafted jewelry and traditional beadwork, using various metals, semiprecious gemstones and glass beads, and draw cultural inspiration from their heritage and natural inspiration from the landscape. “Having a show like this in Maine takes native people and pulls us out of the past and puts us in a modern context,” said Jason Brown. “We’re still here, we’re still alive and still creating. We are not historical relics.”

Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or at:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story