Weekend after weekend, Maine’s high school football schedule offers the same alarming results: the majority of the games are one-sided.

“Oh God, it’s brutal,” said Randy Ouellette, 37, of Lebanon. “Football is a passion of mine and it just seems the wheels have been flattened.”

The quarterback for Noble High’s 1997 state championship team, Ouellette has seen his share of blowout losses while watching his son Blake, a sophomore two-way starter. Noble has lost games this year by scores of 61-7 and 32-0.

But competitive disparity is not just a problem for a handful of schools. Nor is it a new phenomenon.

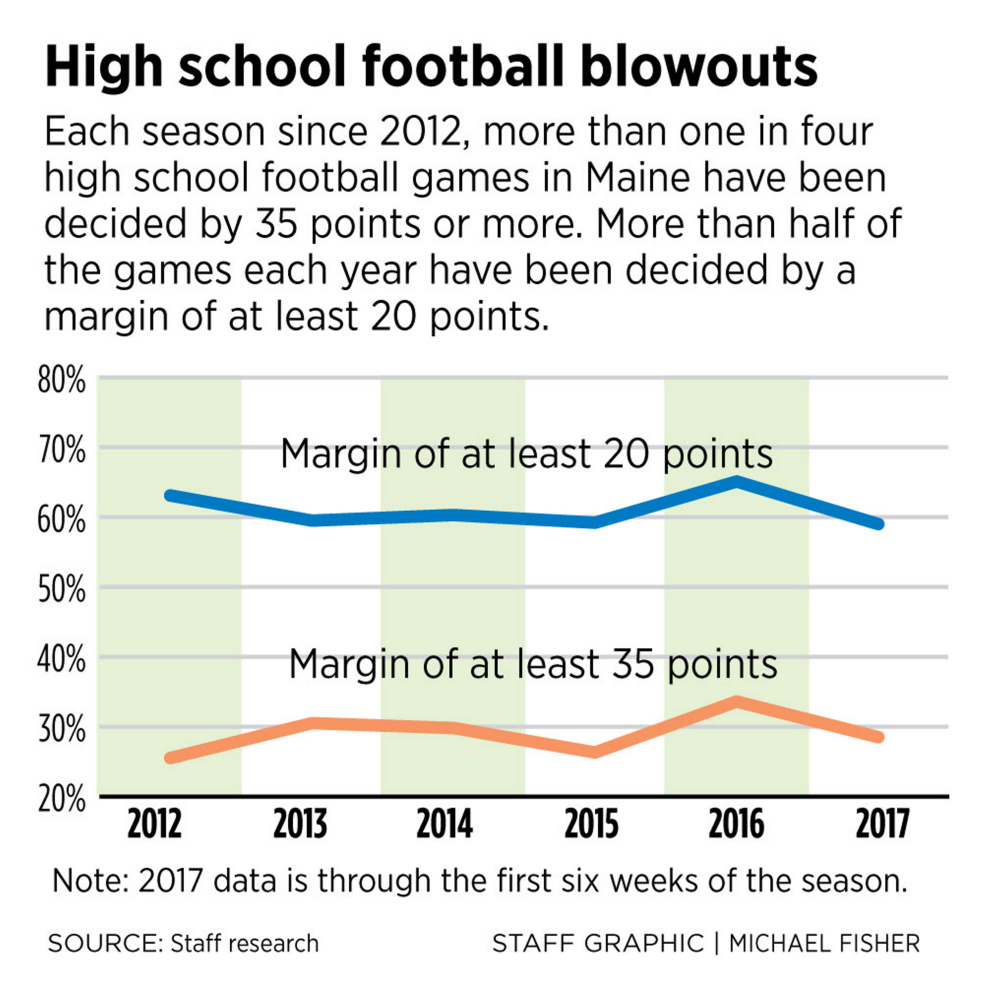

Since 2012, more than 60 percent of games have been decided by a margin of at least 20 points. Nearly 30 percent have reached the 35-point threshold, which prompts “running time” in the second half of games to speed up mismatches.

On Friday, five of the 27 varsity games on the schedule were decided by less than a touchdown – on a night featuring scores such as 41-3, 48-6, 49-0, 51-0 and 56-6.

“As a coach you know when you’re taking a beating but it’s shocking when you hear those numbers,” Yarmouth Coach Jason Veilleux said.

The Maine Principals’ Association, which oversees high school sports in the state, has taken significant steps over the past five years to address the issue. But so far there has been little effect.

“I don’t see the big-score games leaving anytime soon,” said Gene Keene, a longtime athletic administrator and coach in his second year as head football coach at Poland Regional. “As hard as the coaches and the athletic directors work at it, it’s a tough, tough situation.”

RETURN TO FOUR CLASSES

In 2013, after four years of discussions with school officials, the MPA expanded football from three enrollment classes to four. The move was made to develop greater competitive balance with the hope that smaller programs, encouraged by more positive results, could attract more students to play.

Instead, 35-point margins became more frequent, going from 25 percent of games in 2012 to 30 percent the next two seasons. Five schools halted their varsity programs between 2012 and 2016.

In 2015, the MPA instituted a rule requiring the game clock to keep ticking in the second half of runaway games. But the blowouts kept coming. Last year was worse than ever: One-third of all games were decided by at least 35 points.

This fall, the MPA has added a fifth class – the developmental Class E – that allows programs struggling to maintain adequate roster sizes to compete largely against each other. The six members of Class E include four of the five schools that had dropped their varsity programs in recent years.

The move has helped some of those schools find a competitive footing. Nine of the 14 games pitting Class E teams have been decided by less than 20 points, through Friday. But Class E member Traip Academy of Kittery suspended its varsity schedule after the third week of the season because it lacked enough players.

Also this fall, crossover games have been added in classes B, C and D with the expressed intent of creating more evenly matched contests.

The frequency of lopsided games decreased slightly through the first six weeks of the 2017 season compared with the five-year average from 2012-2016.

A Deering player grabs his helmet after Bonny Eagle scored a touchdown Friday. “Even though we have the most high schools playing football in Maine that we’ve ever had, not all are very well-populated,” said Mike Haley of the Maine Football Coaches Association. Staff photos by Brianna Soukup

Still, fewer than a quarter of the games were decided by less than 10 points and 28 percent have hit the running-time threshold.

“I’m not sure what can be done at this point,” said Gordie Salls, the athletic director at Sanford High. “The MPA, the coaches and the leagues are all on board with trying to eliminate some of this.”

STATEWIDE ENROLLMENT DOWN

For roughly 20 years, from the first Class A playoff in 1967 until the mid-1980s, the number of schools playing football in Maine hovered around 60. Over the next decade, a handful of schools dropped the sport.

By the late 1990s, the trend reversed. Traditional soccer towns in Greater Portland started high school football programs and new consolidated schools across the state also joined the ranks. Bonny Eagle, now a Class A power, got a jump on the competition, beginning varsity play in 1994 and moving to Class A in 1996. Scarborough, Windham and Mt. Ararat soon followed, with Falmouth, Greely, Cape Elizabeth and Maranacook beginning varsity play in 2003.

By 2011, the number of teams in Maine had reached the high 70s, as several smaller schools also started programs, including Yarmouth in 2007; Freeport, Camden Hills and Sacopee Valley in 2009; and Hermon, Washington Academy and Telstar in 2011.

But within five years, Camden Hills, Sacopee Valley and Telstar (along with longtime football program Boothbay Region) had shelved their varsity programs.

“Even though we have the most high schools playing football in Maine that we’ve ever had, not all are very well-populated,” said Mike Haley, executive secretary of the Maine Football Coaches Association. “That’s one reason we’re having some of the lopsided scores we’re having. They’re trying to establish a program.”

While the number of football programs grew, enrollment at Maine high schools declined sharply, particularly north of Portland. Statewide high school enrollment has decreased by nearly 11,000 students – or 16.2 percent – since the 2006-07 school year.

In 1999, 3,624 students from 65 schools played football. Last season 3,631 football players represented 82 schools, including those involved in co-op programs.

“When you look at the number of kids in programs, across the state, those have been diminishing,” Salls said. “When the numbers are diminishing, and you’re struggling, and not winning, it’s hard to attract kids.”

Roster size – or more accurately “roster depth,” as Fryeburg Coach David Turner put it – is the surest way of judging a mismatch. An undermanned team may compete well for a quarter or two but more times than not it becomes a tired, defeated outfit.

“Then all of a sudden the other team hits a big play and one score turns into two scores and then it comes down to, ‘OK, here we go,’ ” Turner said.

PITFALLS OF RECLASSIFICATION

With the exception of football’s Class E, teams in Maine high school sports compete in divisions that are grouped by student enrollment. Every two years, the MPA reclassifies schools based on latest enrollment figures.

Reclassification, while intended to help level the field, can put some football teams at a competitive disadvantage. This year four former Class B teams moved into Class C and five former Class C teams moved into D. The shifts have proven beneficial for teams that moved down, but not for holdovers like Yarmouth. The Clippers, regional Class C champs in 2015, won their first game Friday night after a starting the season with six losses. Yarmouth has lost games this fall by scores of 44-0 and 53-7.

“Last year we struggled, and then the conferences changed and boy did that make a difference for us,” Veilleux said. “The three teams we beat last year are now in Class D. As a Class C team stuck in the middle, we knew it would be a challenge for us.”

Rather than grouping teams strictly by enrollment, another option would be to look at factors such as past success, roster size, and the ability to field sub-varsity teams.

“In order to make things as competitive as possible, there has to be other factors than simply (enrollment),” said Fryeburg’s Turner. “Looking at records over the past ‘X’ number of years, that should play into it.”

But even that alternative could be problematic.

“Outside of enrollment, which is a very clear number, everything else is very subjective and there hasn’t been any agreement on what to use as other factors,” said Mike Burnham, assistant executive director of the MPA. “It’s just very difficult because you’re basing it on athletes that may have left your program.”

Burnham pointed to Brunswick as an example of how past success does not always accurately predict the future. The Dragons played in three straight Class B championship games from 2014-16 and won the state title last fall. This season they started 0-6 before earning their first win Friday night.

Coaching is another factor in the disparity between haves and have-nots. Perennial powers have long-tenured head coaches, usually supported by experienced assistant coaches. Teams that struggle annually tend to replace coaches often.

“There aren’t enough good coaches and there aren’t enough guys who come into the coaching ranks with the background that is needed to coach,” said Haley of the coaches’ association. “That doesn’t mean they can’t learn it and that they don’t learn it, but initially it’s a lot tougher for those guys.”

Yarmouth senior captain Hunter Harrington, a defensive tackle and offensive guard, said players are keenly aware of competitive disparity in Maine football.

“We’ve been talking about it the last four years. Everyone talks about this,” he said. “I don’t think (a team’s strength) is based off school population. I don’t have the right way of fixing everything. I don’t have a solution. But I know that if you’re basing it solely off (enrollment) and that’s how you’re pairing teams against each other, it doesn’t always work out.

“Here at Yarmouth, we have a great football program, we have amazing coaches, but we don’t have the personnel in that way because our school is more focused toward soccer. You go against a team like Wells, which is Class D right now, and they have 60-plus kids on their roster. Same with Winslow, where our coach came from. Their school is focused on football.”

Teams can petition to move down to a smaller enrollment class, but are then ineligible for playoffs.

“So no one wants to go down and be ineligible for playoffs,” said Yarmouth’s Veilleux. “I’m hoping down the road that (rule) would change if you had something like two-thirds agreement from the coaches in a league.”

Ultimately, any change still depends on the players, coaches and administrators of struggling programs working hard to improve. But that task gets harder when lopsided losses keep mounting.

“I always say to my son, if you guys stick together you’ll definitely get better,” said Ouellette, “but unfortunately they’re probably going to lose some kids because of the losing record and getting beat up all the time.”

Steve Craig can be contacted at 791-6413 or at:

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story