Gov. Paul LePage’s assertion, made this week during a radio interview, that thousands of Mainers fought on behalf of the Confederacy in a war that began over property rights, offers an opportunity to reckon with Maine’s contribution to the Civil War.

When years of tension over the fate of slavery in the United States erupted in war in April 1861, thousands of Mainers enlisted to serve on behalf of the Union cause realizing slavery to be the source of the conflict. According to contemporary accounts, Mainers’ patriotism was palpable.

“Get the blood of Maine up and she will cling to the old flag through all the battles the Fates shall decree,” wrote Nelson Dingley Jr., editor of the Lewiston Daily Evening Journal on April 20, 1861. “We have never witnessed anything like it. The whispering pines are roaring for war like a thunderbolt.”

From the outset, Mainers argued that the war was a conflict between liberty and slavery, and took measures – well ahead of President Lincoln – to ensure that Union victory would result in the destruction of slavery. As Alonzo Garcelon, future surgeon general to the Maine troops, wrote on April 24, 1861, “May our Rulers not falter for the people are with them in this great struggle of Liberty against Slavery.”

Members of the Maine clergy were among the most vehement in describing the war as a battle between freedom and slavery.

In April 1861, A. C. Adams, a Congregationalist minister in Auburn, preached on “The Southern Rebellion,” predicting that the Union would end the cursed cause of strife – slavery – no matter “the cost of treasure and of blood.”

The cost of blood included the sacrifice of Maine soldiers, of whom more than 70,000 would eventually serve on behalf of the Union – the highest proportion in relation to population of the entire North.

Maine soldiers joined the likes of Garcelon and Adams in defining the war as a struggle between liberty and slavery. In one letter, Albert B. Soule, of the 23rd Maine, even described a “perfect little underground railroad” of his own making, assisting the enslaved to freedom while he was encamped in Maryland.

Other Maine soldiers shared Soule’s outlook.

According to his memoir, William Berry Lapham of Oxford County took singular pride in his contribution to the destruction of slavery. A private in the 20th Maine, Theodore Gerrish, considered emancipation the paramount consequence of the war, even above restoration of the Union.

On the Maine home front, a coalition of Republicans and pro-war Democrats believed that ending slavery was essential for Union victory. Newspapers, such as the Bangor Daily Whig & Courier, Lewiston Daily Evening Journal, and Portland Advertiser gave voice to this perspective.

As an Oct. 22, 1861, editorial in the Lewiston Daily Evening Journal titled “The Rebellion’s ‘Heel of Achilles'” contended, the Confederate war effort could best be disrupted by dismantling slavery.

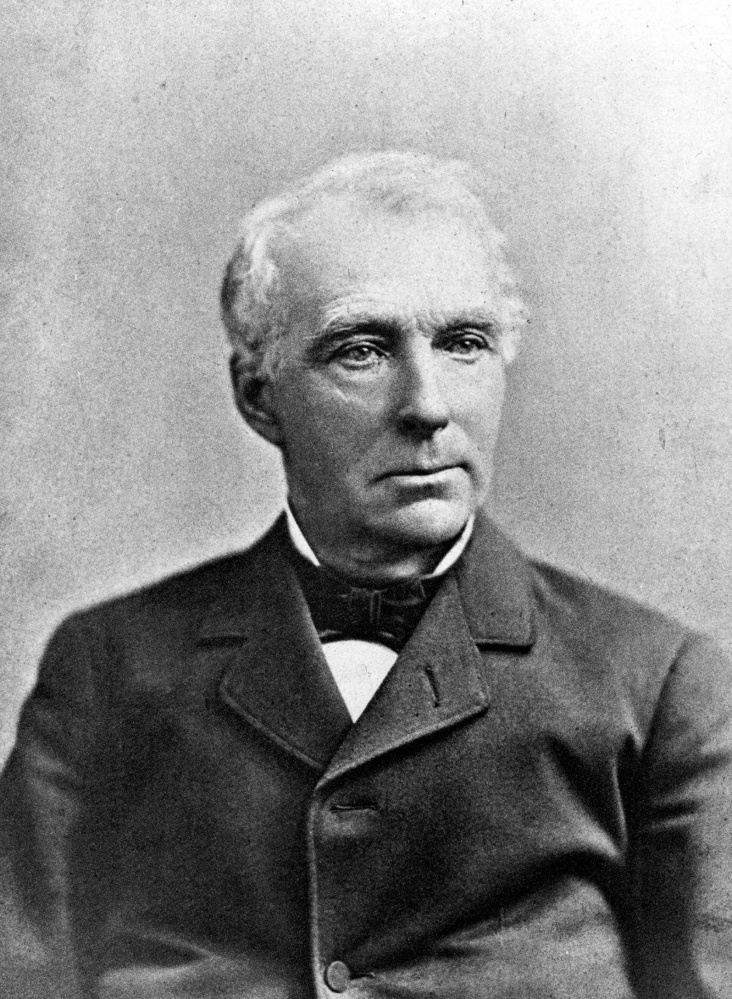

Maine governor Israel Washburn echoed this sentiment in his annual address to the state in January 1862. If the Union could secure victory “by striking the chains from the slaves of rebels,” Washburn argued that every patriotic Mainer would insist on the destruction of slavery.

According to one witness, this line drew the greatest applause in the State House, among an audience of legislators who spent the winter session drafting a bill in support of federal measures to destroy slavery.

Passing this legislation in March 1862, the state of Maine asserted its support for an emancipationist war months before President Lincoln’s own public advocacy of emancipation.

Arguably, states like Maine – insistent on making emancipation a Union war aim – helped convince the president to press forward on emancipation.

When, in September 1862, President Lincoln at last announced his plans for emancipation, Mainers expressed enthusiastic support. Franklin S. Nickerson of the 14th Maine even used the occasion of his furlough that fall to stump on behalf of the president’s proclamation.

With emancipation proclaimed on January 1, 1863, Mainers held fetes, fired cannons, and rang bells in commemoration of a measure that affirmed the Union’s role in upholding liberty over slavery.

Maine’s commitment to ending slavery culminated in February 1865, when the state Legislature endorsed the 13th Amendment, officially abolishing slavery.

The original bill is held in the Maine State Archives, adorned with a purple ribbon – an artifact from an era when Maine citizens not only fought to preserve the United States, but to eradicate the scourge of slavery.

This is a legacy that deserves commemoration.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story