Former acting attorney general Sally Yates said Monday she warned the top lawyer in the White House that then-National Security Adviser Michael Flynn could be blackmailed by Russia, and gave the White House a private warning “so that they could take action.’’

Testifying about her discussions in January with Trump administration officials, Yates gave her first public accounting of a conversation with White House counsel Donald McGahn that ultimately led to Flynn’s firing.

“We began our meeting telling him that there had been press accounts of statements from the Vice President and others that related to conduct that Gen. Flynn had been involved in that we knew not to be the truth,’’ said Yates. “The vice president was knowingly making false statements to the American public, and Gen. Flynn was compromised by the Russians.’’

Though Yates would not discuss classified details of the Flynn matter, other people familiar with the matter said the issue she raised to McGahn were conversations between Flynn and Russian ambassador Sergey Kislyak, in which the two discussed easing U.S. sanctions against Russia.

“The first thing we did was to explain to Mr. McGahn and say the underlying conduct that Gen. Flynn had engaged in was problematic in and of itself,’’ she said.

But the larger issue, she added, was the Justice Department concern that the Russians could try to use the information to manipulate Flynn.

The Russians “likely had proof of this information and that created a compromise situation—a situation where the national security adviser could be blackmailed by the Russians,’’ Yates said. “Finally we told them we were giving them all of this information so that they could take action.’’

After the initial meeting, Yates met with McGahn the following day to discuss the issue further. White House officials questioned why the Justice Department would care if one government official may have lied to each other.

Yates said she emphasized that she was trying to warn them of a potential future vulnerability to Russian intelligence operatives.

“We were really concerned about the compromise here and that is why we were encouraging them to act,’’ she said. Yates said she did not urge the White House to take any specific action, such as firing Flynn. Asked if she thought Flynn had lied to the vice president, Yates replied: “That’s certainly how it appeared, yes.’’

She said McGahn asked if White House officials could review the underlying intelligence that prompted her concerns, and she agreed to that request, though it was unclear if any White House officials ultimately read the material.

Yates spoke before a Senate judiciary subcommittee on Russian interference in the 2016 presidential race.

She said foreign interference in U.S. elections poses “a serious threat to all Americans,’’ as she began testifying at a packed hearing about her warning to the White House about Flynn.a

At the outset of her much-anticipated testimony, Yates promised to “be as fulsome and as comprehensive as possible’’ while noting that there were classified issues she cannot discuss, and legal issues that prevent her from testifying about other matters.

“The efforts by a foreign adversary to interfere with and undermine our democratic processes — and those of our allies — pose a serious threat to all Americans,’’ Yates said in her prepared remarks before questioning from lawmakers on the Senate Judiciary subcommittee.

Yates was the attorney general for only 10 days — an Obama administration holdover whose role was to quietly manage the Justice Department until the Trump administration could quickly replace her. Instead, her brief time in the job has fueled months of fierce political debate about the White House and Russia.

Yates began testifying before a Senate subcommittee that plans to grill her about discussions she had with the White House — testimony that was delayed for more than a month after a previously scheduled appearance before a House committee was canceled amid a legal dispute over whether she would even be allowed to discuss the subject.

Lawmakers have long wanted to question Yates about her conversation in January with White House counsel Donald McGahn regarding then-national security adviser Michael Flynn. People familiar with that conversation say she went to the White House days after the inauguration to tell officials that statements made by Vice President Pence and others about Flynn’s discussions with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak were incorrect, and to warn them that those contradictions could expose Flynn or others to potential manipulation by the Russians.

On Monday morning, President Trump took aim at Yates in a possible attempt to divert the focus of her testimony by urging the subcommittee to raise questions over alleged classified leaks.

“Ask Sally Yates, under oath, if she knows how classified information got into the newspapers soon after she explained it to W.H. Council,” wrote Trump in a Twitter post early Monday, apparently misspelling the word counsel. He later retweeted the message with the word spelled correctly.

But Trump offered no further details about his suggestion that Yates had knowledge of who may have leaked classified information to reporters.

Trump and congressional Republicans have repeatedly sought to shift the focus of hearings about Russian election year meddling to questions about who in the U.S. government may have leaked details about the FBI’s probe into possible coordination between Trump associates and Russian officials.

Yates’ testimony is expected to contradict public statements made by White House press secretary Sean Spicer and White House Chief of Staff Reince Priebus, who described the Yates-McGahn meeting as less of a warning and more of a “heads up’’ about an issue involving Flynn.

In February, Spicer told reporters that Yates had “informed the White House counsel that they wanted to give a heads up to us on some comments that may have seemed in conflict … The White House counsel informed the president immediately. The president asked him to conduct a review of whether there was a legal situation there. That was immediately determined that there wasn’t.’’

The same month, Priebus described the Yates conversation in similar terms, telling CBS’s “Face the Nation’’ that “our legal counsel got a heads up from Sally Yates that something wasn’t adding up with his story. And then so our legal department went into a review of the situation … The legal department came back and said they didn’t see anything wrong with what was actually said.’’

People familiar with the matter say both statements understate the seriousness of what Yates told McGahn and that she went to the White House to warn that Flynn could be compromised — or blackmailed — by the Russians at some point if they threatened to reveal the true nature of his conversations with the ambassador.

Those people said that although Yates’s testimony may contradict Spicer and Priebus, her appearance Monday is unlikely to reveal new details about the FBI’s investigation into whether any Trump associates coordinated with Russian officials to meddle with last year’s presidential election, in part because many of the details of that probe remain classified.

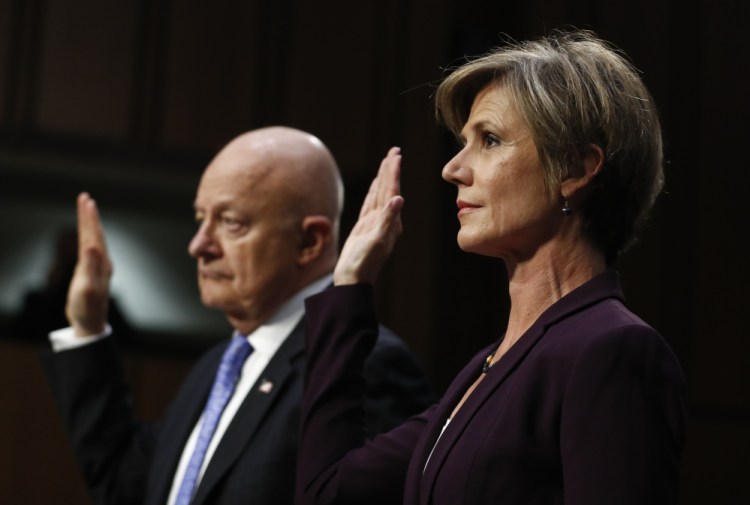

Former director of national intelligence James R. Clapper Jr. also testified at Monday’s hearing. Lawmakers had invited another Obama administration official, Susan E. Rice, to testify, but she declined.

Rice, who served as Obama’s national security adviser, has been under scrutiny from Republicans who have suggested that she mishandled intelligence information involving Americans. Trump said she might have committed a crime when she asked intelligence analysts to disclose the name of a Trump associate mentioned in an intelligence report, a practice known inside the government as “unmasking,” though he has offered no evidence to back up that accusation. Rice has said she did nothing improper.

Before she became acting attorney general, Yates was the No. 2 official at the Justice Department in the final years of the Obama administration. Yates had spent decades in the Justice Department as a prosecutor in both Republican and Democratic administrations. Her brief tenure in the top Justice Department job ended days after her meeting with McGahn, when she was fired by Trump over an unrelated issue. She had instructed government lawyers not to defend the president’s first executive order on immigration, which temporarily barred entry to the United States for citizens of seven Muslim-majority countries and refugees from around the world.

At Monday’s hearing, Yates drew the sharpest criticism not over Flynn and Russia, but for how she handled the president’s first travel ban executive order.

Sen. Jon Cornyn, R-Texas, told Yates he was “enormously’’ disappointed she decided “that you would countermand the president of the United States because you disagreed with it as a policy matter.’’

Yates disputed that characterization, saying she viewed the travel ban fight as “a fundamental issue of religious freedom,’’ adding later: “I believed that it was unconstitutional in the sense there was no way in the world I could send folks in there (to court) to argue something we did not believe to be true.’’

Defending her decision, Yates at one point said simply: “I did my job.’’

Her critics were unconvinced, arguing she had improperly sought to stymie presidential authority.

“Who appointed you to the United States Supreme Court?’’ asked Sen. John Neely Kennedy (R-La.). Yates replied: “I personally wrestled over this decision, and it was not one that I took lightly at all.’’

Flynn was asked to resign in February, after White House officials said he had misled Pence about the nature of his conversation with the Russian ambassador.

Anticipation of Yates’s testimony has been building since March, when she was scheduled to testify before the House Intelligence Committee — a hearing that was canceled by the chairman, Rep Devin Nunes (R-Calif.). In the days before the originally scheduled hearing, Yates’s attorney, David O’Neil, had been locked in an argument with Trump administration officials about whether she would be barred by executive privilege from testifying about her conversation with McGahn.

A week before the planned House hearing, O’Neil went to the Justice Department to discuss the issue of her testimony. That day, he wrote a letter to the department in which he said those officials had “advised’’ him that Yates’s official communications on issues of interest to the House panel are “client confidences’’ that cannot be disclosed without written consent. In his letter, O’Neil challenged that interpretation as “overbroad.’’

In response, a Justice Department lawyer wrote back that Yates’s conversations with the White House were probably covered by “presidential communications privilege,’’ and referred him to the White House. As O’Neil awaited a response from the White House, Nunes canceled the hearing, making the legal issue moot.

After The Washington Post reported on the letters, Spicer said it was “100 percent false’’ that the administration had sought to block Yates’s testimony, and said he welcomed it.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story