Emily Drappi still remembers how she felt the first time she saw the real estate listing for Toddy Brook Farm in North Yarmouth.

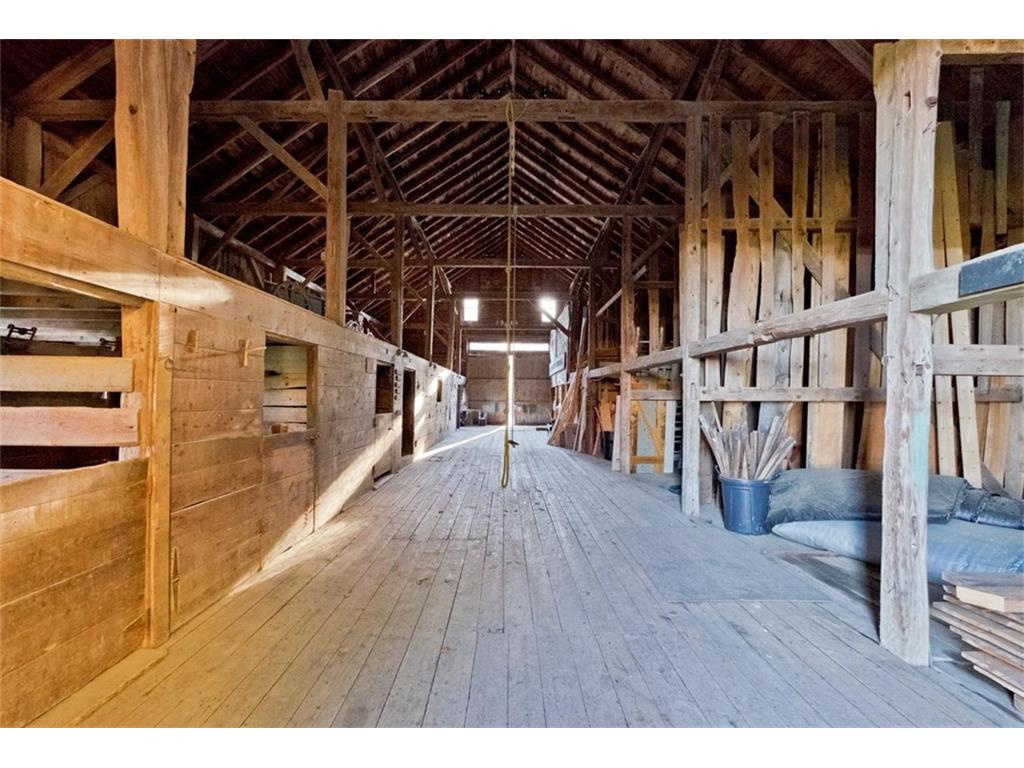

The farm “had a beautiful barn,” she recalled. “Everything about it just looked like my dream house.”

The listing used to sell Toddy Brook Farm, written by Town & Shore Associates broker Gail Landry, called the property “magical,” “transcendent,” “a slice of heaven,” and even “iconic.” It asked potential buyers to imagine what their life would be like if they owned the place:

Emily Drappi watches her sons Leo, left, and Marty play on the property of her North Yarmouth farm.

“There are 14 acres for you to explore. Cool off in Toddy Brook, catch frogs, pick apples from the heirloom orchard and bake a pie. Pack a picnic, gather flowers. At the end of the day as the sun is setting over the meadow, go for a carriage ride. There are two in the magnificent three-story barn for you to choose from. Swing from the rafters.”

Who could resist such a vision? Not the Drappis, who eventually drove by the farm to have a look and fell in love at first sight.

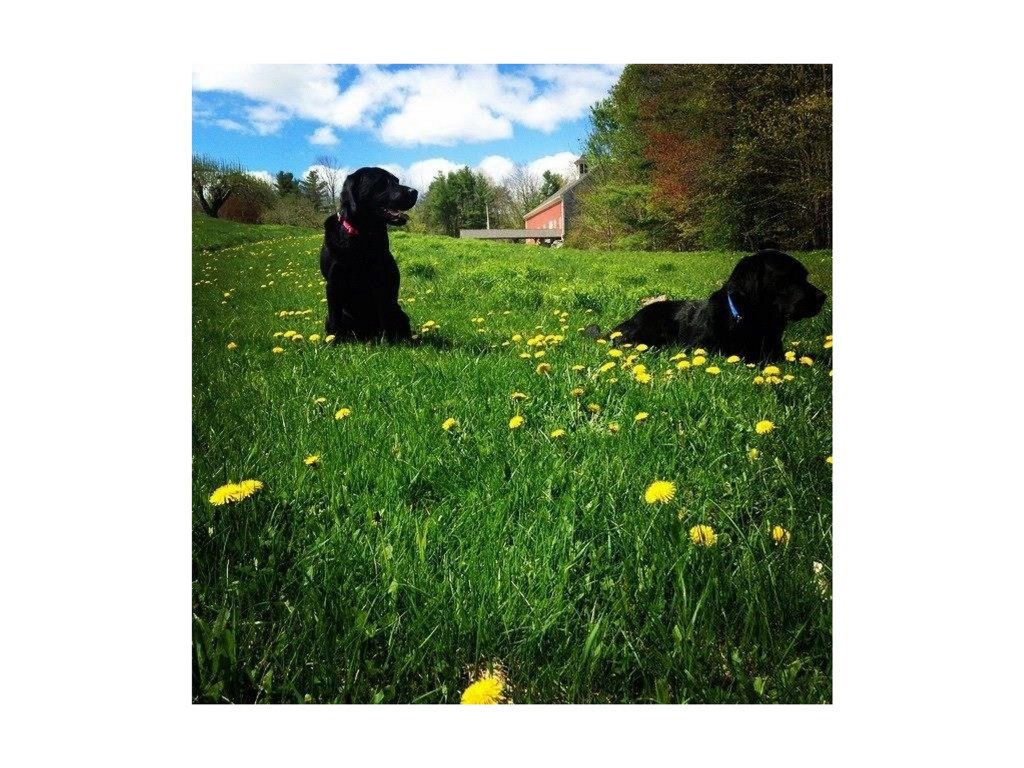

“The previous owner’s black Labs came running out of the orchard as we were driving by,” Emily Drappi recalled. “It was a total Eden, and just exactly what I had dreamed of.”

Emily Drappi holds a week-old duckling for her son Marty to pet at their North Yarmouth farm.

Maine real estate brokers are getting a lot more practice these days selling old – but updated – Maine farms to people who want to try their hand at being a gentleman (or gentlewoman) farmer. These buyers often still work full time, but they fantasize about escaping urban life for a more bucolic existence on beautiful property where they can dabble in farming and maybe raise a few chickens or have a cow.

“It’s not hard agriculture,” said Jonathan Edgerton, a 55-year-old engineer in Bowdoin who has spent the last 28 years building up his own gentleman’s farm on land he bought in 1989. “I don’t have a dairy herd. It’s really more aspiration. I think a lot of people find the idea of being at least partially self-sufficient an attractive idea. I talk to a lot of people who say it is an unrealized dream for themselves.”

John Scribner of LandVest’s Portland office, which specializes in luxury properties in southern Maine, says the business of selling to gentleman farmers “has picked up,” noting his office has sold four “gentleman’s farm” properties in the past couple of years, “and that’s more farms than we’ve done in the past 10 years.”

Drappi and her sons walk through their barn. “Swing from the rafters,” the listing for Toddy Brook Farm coaxed.

One property, a Kennebunk farm listed for $1.25 million, and 80 acres of fields and woods listed separately for $495,000, attracted more than 15 potential buyers who were looking to leave urban life behind and get their kids away from their screens and out into the woods.

“That’s a lot of showings for an expensive property,” Scribner said. Three-quarters of those potential buyers were from Massachusetts, mostly the greater Boston area. They wanted “chickens and a garden and land and privacy.” The men always want a tractor, Scribner said, recalling how some practically swoon when he opens a barn door revealing a stash of farm equipment.

“A couple of them talked about starting farm stands,” Scribner said. “I don’t know if they knew how much work that might be.”

Scribner, who is about to list another gentleman’s farm in Freeport, said he thinks this kind of buyer will only become more common in Maine as more urban workers buy second homes as rural retreats or are allowed to telecommute to the jobs that will pay the mortgage.

“If you can make a Boston salary and live on the coast of Maine,” he said, “it’s a lot cheaper than living in Wellesley.”

Emily Drappi holds a chicken while her son Marty watches at their North Yarmouth farm.

This influx of part-time farmers willing to pay top dollar for Maine farms, if it continues, could end up putting undue pressure on the market for agricultural land, especially if developers start snatching up prime farmland to flip into boutique gentleman’s farms. Ted Quaday, executive director of the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association, says the price of farmland is already “a huge roadblock” to becoming a farmer in Maine.

“We are concerned with any market force that works to drive the price of farmland higher,” he said.

But interest in gentleman farms only seems to be increasing. In February, Edgerton started a Facebook page called “The Gentleman Farmer in Maine” to share his efforts pruning trees, putting in grapevines, baking in his outdoor stone oven, brewing hard cider and beer, and grafting apple trees. (Projects to come: beehives and a smokehouse.)

The Facebook page quickly drew 250 followers, and just two months later that number jumped to 1,500.

To cast a net for all of these potential buyers, real estate agents know which buttons to push. A description of a 14-acre Freeport farm – which was actually advertised by LandVest as a “Gentleman’s Farm on the Harraseeket” – noted its “pastoral” grounds and “stunning” new kitchen that had “soaring ceilings” but also “rustic beams.” It left a trail of written bread crumbs, casually informing buyers that deer and flocks of turkeys might wander across the home’s “rolling manicured lawns.” Asking price: $1.7 million.

Ironically, the only “farming” ever done on the property involved setting out a few potted plants.

“People don’t necessarily have to keep animals in order for it to be considered a gentleman’s farm,” said Landry of Town & Shore.

The properties usually have barn-like structures, fencing, a lot of acreage and an older house, she said.

Skye Farm in Waterford had been owned by an investment banker who turned it into a boutique weekend getaway, adding a pond and a tennis court.

“At one time it was a very famous orchard,” said Scribner, who listed the property. “He had that has a gentleman’s farm for 15 years and just recently sold it to a family from Colorado who wanted to get off the grid. They want to be self-sustaining. They want to bring back the orchards, have bees and grow their own food.”

Emily Drappi enters a greenhouse behind her son Marty at their North Yarmouth farm.

The listing for Skye Farm touted its “true classic New England setting of 180 acres with rolling fields, stone walls, mature forest, beautiful landscaping and distant mountains.” It described the restored farmhouse, the barns, the pond, the apple orchard and water frontage on McWain Pond.

It’s important to talk about the land itself in such listings, said Betsey Ducas of LandVest, who is working on a new gentleman’s farm listing in Parsonsfield.

Landry said buyers are looking for the juxtaposition of the old with the new, the modern with the historic. The listing should note that the house has updated bathrooms and heating systems, but still has a lot of the original character from the year it was built. A kitchen, for example, might have exposed wooden beams hanging over the expensive new appliances and countertops.

“You probably would be referencing the floors – original wide pine floors,” she said. “There probably are lots of fireplaces.”

Landry said it’s usually obvious when a property can be labeled a gentleman’s farm. Toddy Brook Farm, circa 1863, was this kind of no-brainer listing. The previous owner had redone most everything, she said, “and there was this absolutely magnificent barn that they had no intention of putting animals in, except maybe their dogs. And then an incredible orchard with heirloom fruit trees. It was gorgeous.”

The owner was a veteran of the tech industry who was “very much into the bucolic way of life,” Landry said, and he built a great room onto the house that connected the house to the barn. It had a granite fireplace, high ceilings, and exposed beams – it was new, but didn’t look it.

“The room is absolutely stunning,” Landry said. “He felled trees that were on the property, and planed them himself. They were easily 24-inch-wide boards.”

When it came time to list the property, Landry avoided the usual real estate language that focuses on the number of bedrooms and bathrooms.

Emily Drappi walks through the orchard of her North Yarmouth farm with her boys Leo, 4, center, and Marty, 2. The farm has about 40 apple trees in the orchard.

“What I did instead was to suggest a way of life that appealed to people,” she said.

This tactic doesn’t just apply to gentleman farms. Scan the Internet and you’ll find brokers selling not just beach houses but magnificent sunsets and lazy days reading a book while listening to ocean surf. Sotheby’s International Realty lets buyers search properties by lifestyle. There are categories for people who want to live in a vineyard, on a private island, in the mountains, on a ranch, next to a golf course, or in an eco-friendly house.

Marketing a property as a lifestyle rather than a set of rooms and a number of acres is “a subtle but really important distinction,” says David Meerman Scott, a marketing and sales strategist based in the Boston area. “I’m seeing more and more of this.”

Scott tells brokers they should target their listings to “buyer personas” – a demographic group of buyers – and trying to understand what motivates them. Buyer personas who might be interested in buying a gentleman’s farm are “an absolutely perfect example of this concept,” he said.

“In this case, the buyer persona is not gentleman farmer. It’s all those groups of people who might be interested in that lifestyle and fantasizing about it,” Scott said.

They could be newly married couples who want to raise a family in a rural environment; professional people from urban areas looking for a simpler way of life; professionals who live within driving distance of Maine and want a weekend retreat; a buyer who is tired of the beach and wants something different in a vacation property; or someone who grew up in a rural area and dreams of returning to that life.

“A smart real estate person wouldn’t market just the farm,” Scott said. “They’d say here are the attributes of that buyer – income level, the way they think. You put those attributes together and then try to understand how do people who actually fit that demographic think about such a property? What are the actual words and phrases that they would use to describe such a property? How would it make them feel if they were to be owners of that property?”

Emily Drappi and her husband, who bought Toddy Brook Farm last year for $1.1 million, fall into a couple of “buyer personas.” Emily Drappi grew up in Maine, and her family had chickens and turkeys. She lived in Massachusetts for the past 14 years, working for the same large online retailer that still employs her husband. Drappi says she “really wanted to move back to Maine.”

“I always had in my head that I wanted a place where I could have chickens roaming around,” she said. “So the place that really seemed like home to me was the one with the barn and the acreage that was naturally suited for that kind of life.”

The couple, both in their mid-30s, saw the listing for Toddy Brook Farm about a year before they bought the place.

Drappi said she’d eventually like to raise much of their own food. She put in a big garden last year, and bought some chickens and ducklings. A couple of months ago, they brought home some heritage breed piglets to raise for meat. Drappi also plans to start a flower business this year.

But she admits that right now, with much of her energy going to raise her boys, their property falls into the category of “gentleman farm.”

“I think that’s fair because we’re not using it as our primary income,” she said. “Right now I would say it’s not even really a homestead effort.”

So, for now, she enjoys looking through the old photos and ledgers from the farm that she inherited from the previous owner, and whenever she can she tries to put more of her own mark on the place. Last fall, she made cider and gave apples to local bakers. She takes care of the chickens, ducklings and American Guinea Hog piglets.

And every time she goes outside, she takes in her own little “slice of heaven.”

Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at:

mgoad@pressherald.com

Twitter: MeredithGoad

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story