Place your cursor on a photo for buttons that allow you to pause or move ahead at your own pace.

- Joshua Kane, foreground, and Mark Pinkham offload lobster while docked at Cranberry Isles Fishermen’s Co-Op on Little Cranberry Island. Kane, a 32-year-old lobster-fishing apprentice, is a former opioid addict who encourages other fishermen to seek treatment and talks openly about his own addictions. Staff photo by Gregory Rec

- Snow-covered lobster traps sit on a dock in Jonesport. Staff photo by Gregory Rec

- Ben Crocker Sr., right, and Tristen Nelson repair lobster buoys in Crocker’s shop in Bucks Harbor last month. Nelson, a 35-year-old Machias lobsterman who kicked a 20-year heroin habit last year, says: “All those years I didn’t even realize that I had the best job in the world. … What a waste.” Staff photo by Gregory Rec

- Josh Kane and Mark Pinkham offload lobster while docked on Islesford. Kane is a former addict who encourages other fishermen to seek recovery treatment. Staff photo by Gregory Rec

- Tristen Nelson says a prayer with other church members during a service at the Machias Christian Fellowship church. Nelson works as a sternman aboard a lobster boat and went through the Arise recovery program for heroin addiction. Staff photo by Gregory Rec

- A parishoner walks out the door of the Machias Christian Fellowship church as Pastor Aaron Dudley, back to camera at right, talks to men in the lobby. The church supports a faith-based addiction recovery program in Machias called Arise. Staff photo by Gregory Rec

- Tyler Ragone, front center, bows his head as he listens to Weston Kochendoerfer talk about his addiction to opiates and his path to recovery during a community meeting at Machias Christian Fellowship. Ragone, 19, and originally from New Jersey, is in the Arise program. Staff photo by Brianna Soukup

- Vehicles pass over the bridge between Jonesport and Beals Island. Staff photo by Gregory Rec

- VJ Lenfestey, left, of Addison and Wayne Woodman of Machias pray together. Both men belong to Machias Christian Fellowship and often help out with the Arise program. Staff photo by Brianna Soukup

- Men at the Arise house eat lunch and dinner together and rotate through cooking and cleaning duties. Staff photo by Gregory Rec

- Work, including shoveling snow along Elm Street, is a key component of the Arise recovery program. Staff photo by Gregory Rec

- The sun’s rays shine around a dark cloud over Jonesport Harbor. Staff photo by Gregory Rec

- Kristin Seeley holds her son Lucca. His father, Sam Stevens, had returned home from a residential treatment program in Florida to attend the birth of his son, but he died of a heroin overdose two weeks before Lucca was born. Staff photo by Gregory Rec

Eighth of 10 parts.

Until last year, when he finally kicked a 20-year heroin habit, Tristen Nelson had always been too high to even notice the best things about being a lobsterman in Down East Maine, like the beauty of a Bucks Harbor sunrise or the freedom of fishing two dozen miles offshore.

He loves those things about his job now, but for two decades the 35-year-old Machias man only lobstered to make the quick cash he needed to buy heroin. He would spend all his money, up to $60,000 for six months of work, on drugs. And he would end every fishing season broke.

His captains didn’t care if he showed up high, as long as he came ready to work. He hauled traps like a madman at dawn, fueled by his morning fix. By noon, however, the drug would start to wear off. He would slow down and hope each trap hauled was the last.

“I was just one more junkie on a lobster boat, counting down the hours until I could get my cash, until I could score,” Nelson said. “All those years I didn’t even realize that I had the best job in the world. … What a waste.”

The Gulf of Maine is full of people battling addictions. Nelson has hauled traps beside them, shot up with them and attended their funerals. And now, as somebody who has kicked the habit, he is trying to help other fishermen find their way into recovery.

“There are guys like me in every port,” Nelson said. “Anyone says different, they’re blind.”

For years, industry leaders and regulators ignored the drug use. They didn’t want to risk tainting the iconic image of the Maine lobsterman, that rough-and-tumble ocean cowboy who braves the elements to hunt lobster, Maine lobster catch tipped the scale at a record 130 million pounds in 2016, the backbone of the state’s $1.6 billion-a-year industry. And the lobstermen were intensely private, preferring to battle their demons on their own and rarely asking for help.

That is starting to change. As addiction surfaces in newspaper obituaries, public memorial services and fishermen’s forums, and is blamed as a motive for an increasing number of the state’s fishing crimes, industry leaders now admit that America’s deepening opioid epidemic is feeding on the labor force of the state’s most valuable fishery.

“Addiction is a disease and it is a problem within this industry,” Commissioner Pat Keliher of the Department of Marine Resources told the Maine Fishermen’s Forum last month. “I am certainly not making the statement that it is everybody in this industry, but it is a problem.”

There is no way to compare heroin use among Maine lobstermen with any other profession. The state doesn’t keep its drug use statistics that way, and it will not identify the 376 drug overdose victims in 2016, including 313 who died of heroin or other opioids. While some coastal towns, such as Machias, openly acknowledge drug use in the fleet and talk about what can be done, others, like Stonington, the state’s lobster capital, remain reluctant to do so.

“It’s nobody’s favorite topic, that’s for sure, but there’s no denying it’s a problem,” said Dave Cousens, a Spruce Head lobsterman and longtime president of the Maine Lobstermen’s Association. “We all know people who’ve died. We’ve all known about the people who use. My best friend’s son overdosed. My stern girl is a former addict. But nobody knows what to do about it.”

DRUG-CAUSED PROBLEMS LEAD TO FISHING VIOLATIONS

Drug problems that used to be well-hidden are turning into blatant fishing problems. Many of the 42 commercial fishing licenses suspended in Maine last year involved people who broke state fishing laws to buy drugs or hide their addictions, Keliher said. An addicted lobsterman might haul someone else’s traps to cover bills that had gone unpaid because of a drug habit, for example.

Sometimes those crimes set off trap wars, where one lobsterman cuts the lines on another’s gear because a trap was set over his own or because he suspects the person might have stolen lobster from his traps. A turf battle last summer in Blue Hill Bay off Swans Island led to the loss of more than $350,000 worth of gear, making it the most expensive trap war in recent state history.

Opioids played a role in one of Maine’s highest-profile maritime manslaughter cases. Police said lobsterman Christopher Hutchinson was using OxyContin, marijuana and alcohol when he decided to sail his boat into a storm in 2014. His two sternmen died when it sank. The Cushing man faces up to 10 years in prison if convicted when he goes to trial this year. Late last month, while out on a no-drugs-allowed probation for the manslaughter charges, Hutchinson was arrested again after EMTs had to revive him from an apparent heroin overdose.

The state doesn’t know how to rid the industry of opioids. It doesn’t think it can arrest its way out of the problem. Suspending a captain’s fishing license can sentence a whole family to poverty and doesn’t address the issue of addicted sternmen, who are unlicensed. Keliher is exploring whether to adopt a consent agreement process in some cases, which could reduce the length of a drug-related license suspension if an addicted captain gets clean.

Like Keliher, some boat captains say they don’t know what to do about the heroin problem.

Lobster boat captain Ben Crocker Sr., 72, says it’s hard these days to find a drug-free sternman who can last an entire lobstering season. He fired four sternmen in 2016 for drug use, he says, and one of the men died from an overdose two days after being let go.

Boat captain Ben Crocker Sr. fired four sternmen in 2016 for drug use before he hired Nelson, the Machias lobsterman who had stopped using heroin. The 72-year-old captain said it’s difficult to find a clean sternman who can last an entire season. One of the men he let go because of drug use died from an overdose two days later.

“Damned if I do, damned if I don’t,” Crocker said wearily as he worked on traps in his Machiasport workshop.

Sam Stevens, 23, a sternman from Whiting, died from an overdose last March in his father’s Volvo days before his son was born. Brendan Bubar, 27, a sternman from Cherryfield, died from an overdose in an Ellsworth hotel one week later. Caleb Lord, a 28-year-old captain from Lubec, died in November while preparing to enter rehab.

Addiction is killing older fishermen, too. In November, 52-year-old Christopher Delano, a veteran lobsterman in the Friendship fishing fleet, was found dead in his home of an apparent overdose, a packet of heroin in his wallet. His son said he’d been taking painkillers for an injury.

“It’s very common, real common,” Nelson said. “On Monday morning I’ll go to work, it will be me and a guy named Jesse, and then the next morning it will be me and a guy named Mike. I’ll say, ‘Oh, where’s Jesse?’ and they’ll say, ‘Oh, he didn’t make it through the night.’ ”

Paul Trovarello leans on a window while talking on a cellphone at the Arise addiction recovery program in Machias.

HOW HEROIN TOOK ROOT IN THE LOBSTER INDUSTRY

Paul, executive director of the Arise Addiction Recovery House in Machias and a former heroin addict himself, guided Nelson through the recovery process.

Many of the families who attend his church, Machias Christian Fellowship, earn a living from the industry, either as fishermen, trap makers or boat builders. Lobster money helps fund the church, the biggest in Down East Maine, and Arise, the church’s addiction ministry.

When he first moved Down East two years ago, Trovarello worked on a lobster boat out of Cutler. The New Jersey native learned a lot while lobstering, including how heroin took root in the trade.

Migrant blueberry workers told Trovarello that out-of-state drug dealers were drawn to the region by the lobster money. Dealers targeted the seasonal, cash-based lobster business of Maine just like they target the hospitality workers and clients at beach and ski resorts.

Heroin is not the first addiction that has run through the industry. Alcoholism is socially accepted in the fleet. On a good day, when a haul is particularly big, the captain will hand out beers at the selling station to celebrate, even when one of those deckhands is still in high school.

Cocaine and pills, including OxyContin, have had their day, too, Trovarello said. A crackdown on painkiller prescriptions has forced many fishermen with a drug problem to turn to heroin, which is less expensive than pills and easier to get. It’s the drug of choice on the party scene, too.

Some people assume that lobstermen addicted to heroin must use it to address a lingering work injury, but doctors, counselors and recovering addicts say that’s not true for most fishermen who use heroin. They try it because it looks fun, because they’re bored and because it’s everywhere.

HOW TO GET HELP

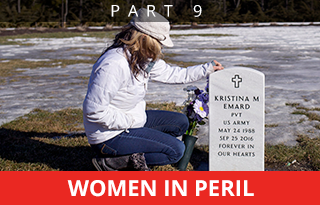

COMING MONDAY: Women in peril: Female addicts face distinct – and deadly – disadvantages

Cameron Reed, a 26-year-old lobsterman from East Machias, started taking drugs with his friends to fit in. He smoked pot in high school, switched to pills, and then sold heroin to make money to buy pills. His friends told him to sample his product to test its quality.

“I always looked down on it,” Reed said. “It only took two days of doing it before I was hooked.”

At the start, he used his substantial pay from the lobster boat to fuel the partying, but by the time he cleaned up last year, he was living in a run-down place with no friends or family left to answer his calls. He spent three months cleaning up at the Arise House, and was one of a handful of Arise boarders who agreed to participate in a film about the heroin epidemic made by students at the University of Maine in Machias.

“I just realized I was broken,” Reed told the student filmmakers. “I was in a bad place. I hurt everybody around me. … It sounds all fun, but it’s far from it. A lot of sickness comes with it, and stealing and robbing. You just feel like a hurricane everywhere you go. There’s destruction everywhere you go.”

Heroin in Down East Maine isn’t cheap. A tenth of a gram that may sell for $5 in New York is $50 up here. But a lobsterman or even a sternman, who usually gets paid in cash at the end of every day, can afford it, and many captains just look the other way, Trovarello said.

“A sternman who’s dopesick, well, he’s useless, but a sternman who’s high? He’s doing all right,” Trovarello said. “Some captains, they’ll make sure their guys are ready to work, make sure they come to work high. And for some, it works. Until it doesn’t. Until they’re dead.”

CHURCH-BASED PROGRAM HELPS ADDICTS RECOVER

Trovarello, a bearded bundle of energy, has made a name for himself with addicts’ families, tracking their loved ones down in drug dens across Washington County. He’ll offer them a blanket, a message of forgiveness and a spot in his 12-bed, Scripture-based residential program in Machias.

Inside the rambling two-story white house, an eclectic mix of recovering addicts from Maine and New Jersey join together to wean themselves off drugs and other sins of the flesh and surrender to God’s will. The program focuses on structure, discipline and Scripture.

Participants sleep in spare bunk beds, chop wood to heat the house and mow lawns to cover program expenses. They share meals together around a large wooden table that dominates the small dining room. They study the Bible together, taking the name of the program, Arise, from the Book of Acts.

“So he, trembling and astonished, said, ‘Lord, what do you want me to do?’ ” says Trovarello, reciting the words of Paul the Apostle at the time of his conversion, in a voice still thick with his New Jersey accent. “And the Lord said to him: ‘Arise!’ ”

Not all of them can answer the call. Caleb Lord, the young lobster captain from Lubec, had gone to a few Arise meetings last fall and planned to move into the house. Lord told Trovarello that he would return as soon as he pulled his traps from the sea. He died the next day from an overdose.

Instead of watching him graduate from Arise, Trovarello spoke at Lord’s funeral. The Lords were one of the growing numbers of Down East families to go public with their loved one’s addiction by including it in the obituary and talking about it at the funeral.

“This battle is very real,” Trovarello said. “Fishermen are dying almost every month.”

Trovarello’s group runs recovery meetings across Down East Maine. Once a week it holds a meeting in the Washington County Jail, which functions as a default detox center. Once a month it has a community potluck where recovering addicts talk publicly about their struggles.

About 75 people attended the February potluck at Machias Christian Fellowship to hear Weston Kochendoerfer of Baileyville talk about how addiction landed him in prison, where he was until a year ago, and how God and an old athletic rival helped rescue him.

His listeners drove through heavy snow and nibbled on skillet cornbread, chowder and frosted cookies to cheer on the fast-talking charmer who is now bringing God’s love to other addicts, including a group on Swans Island, traditionally one of Maine’s big lobster ports.

“I’m ready to go to war for this,” Kochendoerfer told the gathering, who cheered for him when he wrapped up his hourlong testimony. “I want to spread the word that there is hope. There is a cure. You don’t have to be broken. You can lead a real life.”

East Machias seen from Academy Hill. The nearest detox center is 216 miles away and there are no Narcotics Anonymous meetings in most of Down East Maine’s major lobster ports.

LACK OF TREATMENT OPTIONS, INSURANCE PERPETUATE ADDICTION

In the more rural sections of the Maine coast, especially on the islands, the churches have tried to fill the treatment void created by a dearth of substance abuse counselors, residential recovery beds and doctors able to write and manage Suboxone or methadone prescriptions.

The nearest detox center is in Portland, 216 miles from Machias. The county jails and emergency rooms in the small local hospitals or walk-in clinics stand in as the next-best thing. There aren’t any Narcotics Anonymous meetings in most of the major lobster ports, such as Stonington, Vinalhaven or Jonesport.

VITAL SIGNS: In December 2016, with overdose deaths increasing to a rate of one a day, DHHS Commissioner Mary Mayhew announced the state would add 359 medication assisted treatment slots for people with no insurance, at a cost of $2.4 million. And in early March, LePage and lawmakers agreed to include in the supplemental budget an additional $3 million to expand treatment to as many as 400 additional patients who are uninsured or have MaineCare.

For most of the past five years, Charles Zelnick was the only doctor allowed to prescribe Suboxone on Deer Isle, a 30-square-mile island that is home to about 1,900 year-round residents and the state’s largest lobster port of Stonington. He has 16 Suboxone patients, but only a handful of fishermen. Zelnick knows it’s a problem in the fleet, but few fishermen have asked for his help – they are often reluctant patients.

Not that he’d necessarily have room for them. Suboxone treatment is a long-term investment by both the doctor and the patient, with many recovering users taking years to wean themselves off the replacement drug. Spaces in the program don’t open up often.

The practice has recently added a second doctor trained to provide Suboxone. Zelnick hopes that will open the door for some of the island’s fishermen to seek out medication-assisted treatment, which Zelnick believes is the best option for most people.

It can be hard for a lobsterman, especially a sternman who’s not in charge of the boat’s comings or goings, to make it back to shore in time to get a daily methadone dose, which doctors and pharmacists only give out in person to prevent abuse. Sometimes sternmen think they’ll be able to make it back for a therapy session, only to find out their captain wants to stay out longer to take advantage of a calm sea. Suboxone users can more easily manage the unpredictability of a fishing schedule because they can transition to monthly doctor’s visits after a week or two of induction.

But doctors like Zelnick or Dan Johnson, director of the Acadia Family Center in Southwest Harbor, say most medication-assisted treatment providers in fishing ports will work around a lobsterman’s schedule. Johnson has even used video conferencing to work with fishermen in recovery on Matinicus Island, some 20 miles off the Knox County mainland.

Many lobstermen do not have health insurance, especially sternmen. Most lobstermen earn good money, but those who are addicts have often spent it all by the time they seek treatment and have little or no insurance to fall back on.

The number of fishermen with health insurance has increased since 2014, the deadline for individuals to obtain coverage under the 2010 Affordable Care Act. The Maine Lobstermen’s Association has helped its members sign up, with many enrollees specifically asking for drug treatment plans.

Josh Kane is a former addict who encourages other fishermen to seek recovery treatment.

LOBSTERMEN TEND TO HIDE FEELINGS, LIFE’S DIFFICULTIES

The challenge of working out logistics and payment plans for uninsured lobstermen is not nearly as hard as getting them to talk about the causes of their addiction, said Johnson, who worked in Acadia Hospital’s narcotics treatment program in Bangor for 20 years.

“Mainers are a proud people who don’t like to ask for help,” Johnson said. “A lobsterman? That is probably the most ‘Maine’ you can get. They don’t want to talk about their feelings. Problems? They’ll take care of them on their own, thank you very much.”

The Acadia Family Center decided to combat that stigma by asking a fisherman to serve on its board of directors. In Joshua Kane, a 32-year-old lobster fishing apprentice from Bar Harbor, it landed a fisherman who is five years clean from a nine-year opioid addiction.

Kane said his alcoholism helped him hide his drug problem from most people, including his captain at the time, who had a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy about drugs on the boat or coming to work high. Kane was a hard worker, high or not, so his boss didn’t mind, he said.

Kane decided to quit when a girlfriend noted that lobstermen were well-paid but always broke.

“It was right at the start of fishing season, and I realized how hard I was going to be working that summer, but how she was right, I’d be broke by winter,” Kane said. “I realized I was never going to get anywhere as long as I was using. I also quit because of my children. I had a good upbringing, so I knew right from wrong. I wanted them to grow up in a healthy, safe environment.”

Clad in a bright-orange sweatshirt and waterproof bib overalls, Kane is a tall, good-looking man. He talks freely about his alcoholism and addiction on the boat ride home from Islesford after an especially mild February day spent hauling lobsters near Mount Desert Rock.

The weather was so nice that his new captain, Jack Merrill, stayed out as long as he could. The sun had set by the time Merrill pulled the Tigger, his 42-foot lobster boat, up to the Cranberry Isles Fishermen’s Co-Op in Islesford to sell his lobsters, but Kane didn’t use the darkness to hide his mistakes or his feelings.

“It’s hard to get fishermen to talk about the kinds of things that make us drink and do drugs,” he said. “We have a soul. We look at sunsets and think they’re pretty, but we don’t talk about them. We don’t admit they’re pretty, don’t admit we think about them.”

Kane looked at Merrill, a man of few words, and then at the other sternman, his cousin.

“Feelings don’t fly in this business, you know?” he said. “But keeping quiet isn’t working either.”

Last year the state suspended 42 fishing licenses, including 12 held by lobstermen, according to state records.

MARINE REGULATORS LIMITED IN DEALING WITH DRUG ABUSE

While the state and many within the industry agree there is a problem, how to handle it provokes disagreement.

Random drug testing of lobstermen has come up for debate before, but disputes arise over who should pay for it, or what should be done with violators.

Under current law, the Coast Guard or Maine Marine Patrol can require boat captains to be tested for drugs if they are involved in a marine accident, are piloting their boat erratically, or if, during the course of a routine boat inspection on the water, authorities see drugs or drug paraphernalia on the boat or can tell the captain is visibly impaired.

Sternmen cannot be charged simply for being high, because they are not operating the boat. But they can be charged with possession if the officers see drugs on them during the course of a boarding. And captains can be held liable for any conservation crime their sternmen may commit while high, even if it was unintentional or because of bad judgment, especially if the captain knows the sternman is using drugs.

Neither agency has penalized a commercial lobsterman for using drugs, at least not in recent memory, according to the marine patrol and the Coast Guard. Marine patrol believes its mission is to enforce the state’s conservation laws and protect the lobster population from being overfished. It barely has enough officers to make sure fishermen aren’t scrubbing the eggs off female lobsters, to settle feuds over who has the right to set their traps in which territory, and to keep fishermen from hauling each other’s gear, said Col. Jonathan Cornish, the marine patrol’s highest-ranking officer.

The state doesn’t have the money to pay for random drug testing. Marine patrol is looking into funding through the Maine Bureau of Highway Safety to train officers as drug recognition experts that can recognize fishermen who are under the influence of drugs, which can be especially difficult for people using heroin and opiates. “We’re committed to addressing this issue,” Cornish said.

The state has the power to revoke a lobster license, as well as any other fishing license a fisherman may hold, for a range of conservation crimes. As the head of the Department of Marine Resources, Keliher has broad discretion over how to handle people who break the state’s fishing laws, ranging from fines to suspensions to permanent license revocation. He doesn’t have that same power over sternmen, however, because they usually don’t have a fishing license to revoke.

Last year the state suspended 42 fishing licenses, including 12 held by lobstermen, according to state records. None of the suspensions was for drug use, but many were for fishing violations committed so the fisherman could earn extra money to either buy drugs or cover up the financial implications of his or her drug habit. One fisherman caught breaking a fishing law last year told the marine patrol he needed the money to hide his drug habit from his wife.

“It’s become a resource problem, too,” Keliher said of addiction. “A conservation crime hurts the resource, and it’s a resource the industry and the state depend on.”

While the crimes are serious, taking a lobsterman’s license is “a really big deal” too, Cornish said. Many fishermen would prefer huge fines, even jail.

Fishermen often reveal gut-wrenching details of their addictions during license suspension hearings, Keliher said.

“Those are just the saddest things in the world to see,” he said, shaking his head.

USING THREAT TO LIVELIHOOD TO GET FISHERMEN IN REHAB

Keliher said he doesn’t factor a violator’s drug use into the decision to suspend or revoke a license. However, he is exploring the idea of establishing a consent agreement process where a suspended fisherman can return to the fishery early if he or she agrees to certain terms and conditions, like submitting to regular drug tests or successfully completing a drug rehabilitation program. This “carrot and stick” idea is still in its early stages, he said.

A survey of lobstermen’s association members presented at the Maine Fishermen’s Forum this year found members had little tolerance for those who break state fishing laws, regardless of the reason. The survey results prompted the association to put forward a proposed bill that would establish mandatory minimums for certain conservation crimes – requiring revocations in certain cases and demanding restitution paid to the victims in others.

“It’s about a level playing field,” said Cousens, the association president. “We want addicts to get the help they need, but people who aren’t following the law don’t belong out there on the water with the people who do, it’s as simple as that.

“I’m sorry they’re addicted. I don’t think they’re a bad person, but I also don’t think they are a lobsterman anymore, not really. They’re putting the drugs before the fishing.”

This story was updated at 4:09 p.m. April 13, 2017 after the Maine Attorney General’s Office revised its preliminary estimate of the number of drug overdose deaths in 2016.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story