DETROIT — If President Trump goes ahead with his threat to tax Mexican-made cars sold in the U.S. it will throw the auto industry into disarray, analysts say, forcing some uncomfortable choices: Raise car prices or swallow the cost. Stop selling Mexican-made cars in the U.S. but risk losing customers. Move production to the U.S. but make less money.

“I don’t think the auto industry would turn up its feet and die, but it would be a terrible shock. It would create mayhem with their profitability,” said Marina Whitman, a business professor at the University of Michigan and a former vice president at General Motors Co.

Trump hosted a breakfast meeting early Tuesday with the heads of General Motors, Ford Motor Co. and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles. Before the meeting, Trump tweeted that he wants “new plants to be built here for cars sold here.” He has warned of a “substantial border tax” on companies that move manufacturing out of the country and promised tax advantages to those that produce domestically.

Automakers expressed optimism after the meeting.

“I think as an industry we’re excited about working together with the president and his administration on tax policies, on regulation and on trade to really create a renaissance in American manufacturing,” said Ford CEO Mark Fields.

But after closing 13 U.S. assembly plants during the recession to deal with excess capacity, Detroit automakers aren’t eager to open new ones, especially now that U.S. sales of new vehicles are slowing after reaching record levels. The three automakers currently operate 27 assembly plants in the U.S. and seven in Mexico.

For more than two decades, Mexico has been an oasis for the auto industry, offering cheap labor and access to dozens of markets through free-trade deals. Whitman says Detroit automakers can’t build small cars profitably in the U.S., where a unionized auto worker can make $58 an hour in wages and benefits. By comparison, a Mexican auto assembly worker makes a little more than $8 an hour.

That helps to explain why automakers have announced $24 billion in Mexican investments over the past six years, according to the Center for Automotive Research, a Michigan think tank. In all, vehicles worth $50.5 billion and auto parts worth $51 billion were shipped to the U.S. from Mexico in 2015, U.S. government data show.

Mexico’s auto sector, while still smaller than its U.S. counterpart, is growing at a faster clip. Mexico’s vehicle production capacity is expected to rise 49 percent to 5.5 million vehicles by 2023, according to LMC Automotive, a forecasting firm. U.S. capacity is expected to grow 13 percent to 14.2 million vehicles in the same period.

But Trump could change that. In frequent tweets targeting the auto industry, he has proposed both a 35 percent tariff on Mexican-made imports and a “border tax,” which would tax companies’ imports. That’s forcing automakers to consider a number of options.

Abandoning Mexico and moving production to the U.S., as Trump demands, would cost the industry billions and scuttle plans that have been years in the making. Audi, for example, just opened a plant in Mexico that it decided to build five years ago.

“It’s very difficult to turn on your heels quickly in the auto industry,” said Laurie Harbour-Felax, a manufacturing consultant and president of Harbour Results Inc.

In recent weeks, Volkswagen, GM, Toyota and BMW have all said they won’t shift their production plans, while stressing the amount they’ve invested in the U.S. BMW, for example, said it’s proceeding with a $1 billion plant in Mexico that will make the 3 Series sedan starting in 2019. The German automaker also noted that its SUV plant in South Carolina is its largest plant worldwide.

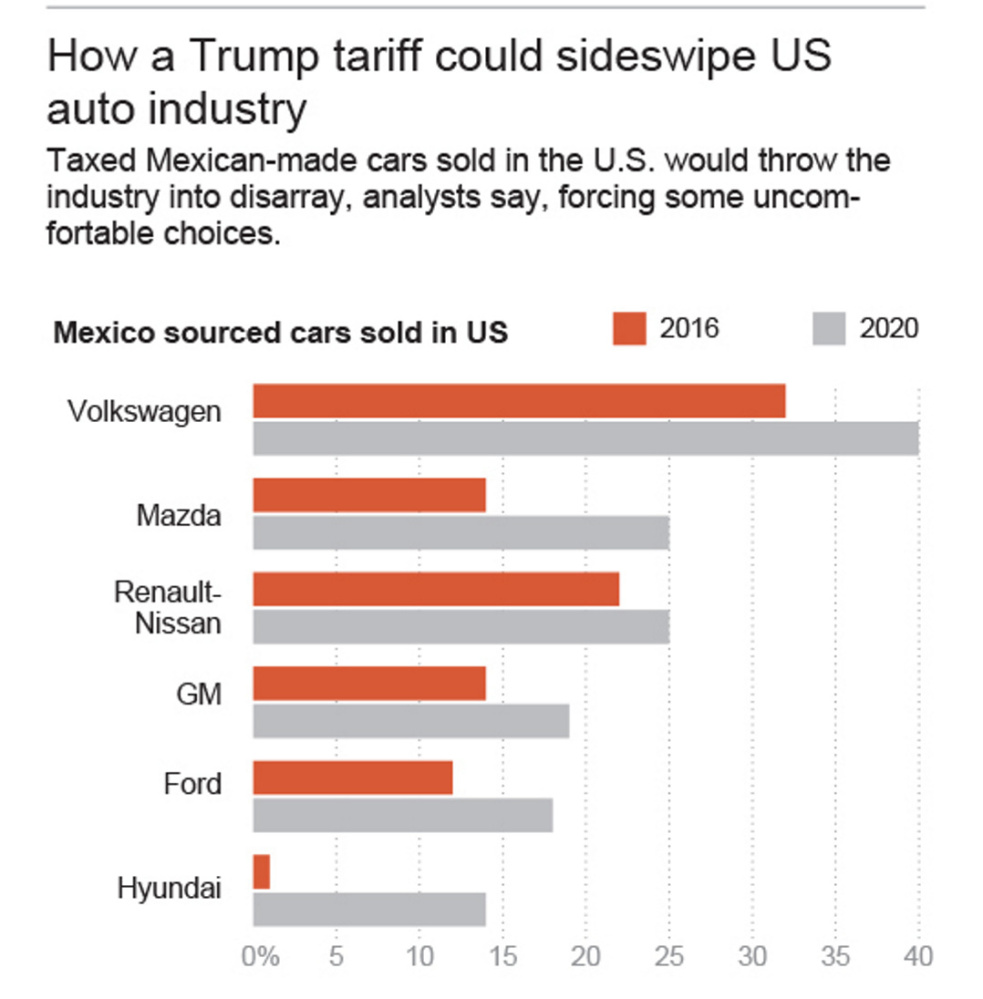

Trump’s border tax would hurt some automakers more than others. Volkswagen, for example, imports 32 percent of the vehicles its sells in the U.S. from Mexico, according to LMC. But Honda imports just 11 percent, and that’s expected to fall this year after it moves production of the CR-V SUV from Mexico to Indiana.

In early January, Ford made the surprise announcement that it would halt construction of a $1.6 billion plant in Mexico that was supposed to build the compact Focus. It also announced plans to invest $700 million of that savings into a Michigan plant where it will make new electric and autonomous cars.

Ford said declining sales of small cars, not Trump, influenced the Mexico plant decision, and the company will still make the Focus in Mexico at a different plant. But Ford CEO Mark Fields noted that Trump’s promise to lower corporate taxes and ease regulations would make it more attractive to do business in the U.S. Fields also said he’s not worried about the possibility of tariffs.

Others appear more nervous. Speaking to reporters at the Detroit auto show, Fiat Chrysler CEO Sergio Marchionne said his company might withdraw from Mexico altogether if tariffs got too high.

“Those plants were designed, built and purposed at a time when (the NAFTA free trade agreement) was alive and well,” he said. “It’s one of the perils associated with the business that we run.”

Trump can’t place tariffs on companies or groups of companies without congressional approval, sais Gary Hufbauer, a senior fellow at the nonpartisan Peterson Institute for International Economics. But he could fashion tariffs that hurt some companies more than others by, for example, picking and choosing from the dozens of import classifications for vehicles and parts.

Automakers could stop selling some Mexican-made cars in the U.S. altogether, but that would cost them customers. They could also try to sell the cars elsewhere.

Mexico has free trade agreements covering 45 countries, including agreements with the European Union, Japan and South America. The U.S. has agreements with 20 countries.

Nissan Motor Co., the biggest producer in Mexico, made more than 823,000 vehicles there in 2015. Forty-six percent were shipped to the U.S., but another 17 percent went to other countries, including Canada and Saudi Arabia. Nissan could tweak those numbers if U.S. tariffs were prohibitive.

“All carmakers will adapt to the new rules, if there are new rules,” Nissan CEO Carlos Ghosn said this month in Detroit.

If Trump imposes tariffs, automakers could try to pass along the cost to U.S. customers. But that would raise the price of cars like the $17,000 Nissan Sentra or the $21,000 Chevrolet Trax by thousands of dollars.

Even a U.S.-built vehicle like the Toyota Camry would cost more. Jim Lentz, CEO of Toyota North America, said 25 percent of the Camry’s parts are imported, and tariffs on those parts would add roughly $1,000 to the cost of the car.

Automakers could swallow the cost of the tariff, but it would hurt their bottom lines.

Dustin Blanchard, 31, who works for a software startup in Austin, Texas, drives a 2007 Nissan Sentra that he bought for $18,000. His car was made in Mexico, but he didn’t think much about that when he bought it.

“The parts all come from everywhere. Domestic brands are made overseas and Japanese cars are made here,” he says. “It’s so interconnected that you don’t feel like it’s a patriotic duty to buy a Ford or something.”

But a 35 percent tariff would have added $6,300 to the cost of his Sentra, which would have put it out of his reach.

Blanchard has thought more about NAFTA’s impact since the election. When he recently drank a Mexican Coke, he says, he half-joked that he better enjoy it while he can.

“It’s something I had taken for granted, that free trade was here to stay,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story