More than politics, the U.S. presidential inauguration has become a show, with celebrity performers, glitzy balls and cameras capturing every moment. It could be said that the trend began with Lincoln in 1861.

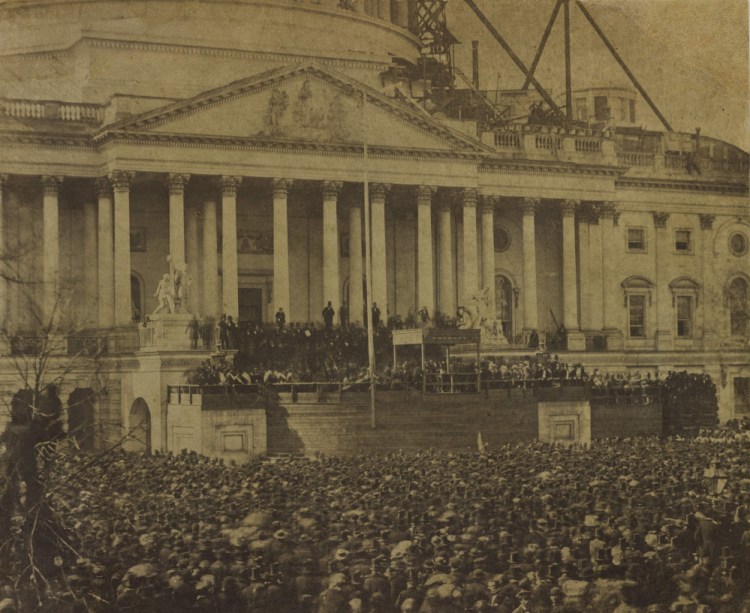

For a few hours Thursday, the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick will display a newly acquired photo of President Abraham Lincoln’s first inauguration, on March 4, 1861, on the east steps of the U.S. Capitol, the first to be captured on film. Bowdoin’s vintage copy is one of three known to exist.

“One might argue, the media moment is born here,” said Frank Goodyear, co-director of the museum. “The idea that an event like this could now be captured using photography, and images circulated far and wide, changed the whole nature of these types of rituals.”

The museum acquired the photo at auction last fall. Goodyear declined to say how much money the museum paid for the photo, which is attributed to the Scottish-American photographer Alexander Gardner. He was a photographer in the Mathew Brady’s Washington studio. Brady is best known for his Civil War photos.

The 10-by-12-inch brown-tinged print will be presented Thursday alongside an engraving by Winslow Homer of the same event. Homer, an illustrator who later moved to Maine and gained international fame for his paintings of the Maine coast, covered the inauguration for the magazine Harper’s Weekly.

The other Maine connection to the photograph is Lincoln’s vice president, Hannibal Hamlin, who was a U.S. senator from Maine.

At 12:30 p.m. Thursday at the museum, Goodyear will talk about the historical significance of the photo and Bowdoin history professor Patrick Rael will discuss the 1860 election and Lincoln’s inaugural address, which foreshadowed the Civil War. Because of its sensitivity to light, the photo will be on view only Thursday afternoon, though Bowdoin plans to show it again in other exhibitions. “We acquired it last October, it arrived in Brunswick in late November, and with the upcoming inauguration a week from Friday we thought it would be an appropriate time for its unveiling,” Goodyear said.

The photo itself doesn’t reveal many details. It mostly shows the backs of spectators, who face the Capitol steps, and a large wooden canopy, under which the proceedings occur. It’s impossible to discern specific figures. Historians have studied the image for decades but can’t identify Lincoln – “we think Lincoln is the tall guy with the hat,” Goodyear quips – or other figures. Gardner made the image from atop an elevated wooden platform.

His photo illustrates a panorama of the crowd below him with the politicians and dignitaries on the Capitol steps. “There was nothing spontaneous about capturing this event,” Goodyear said. “Photographing outdoors was a tricky thing, with cumbersome equipment and sensitive chemistry.”

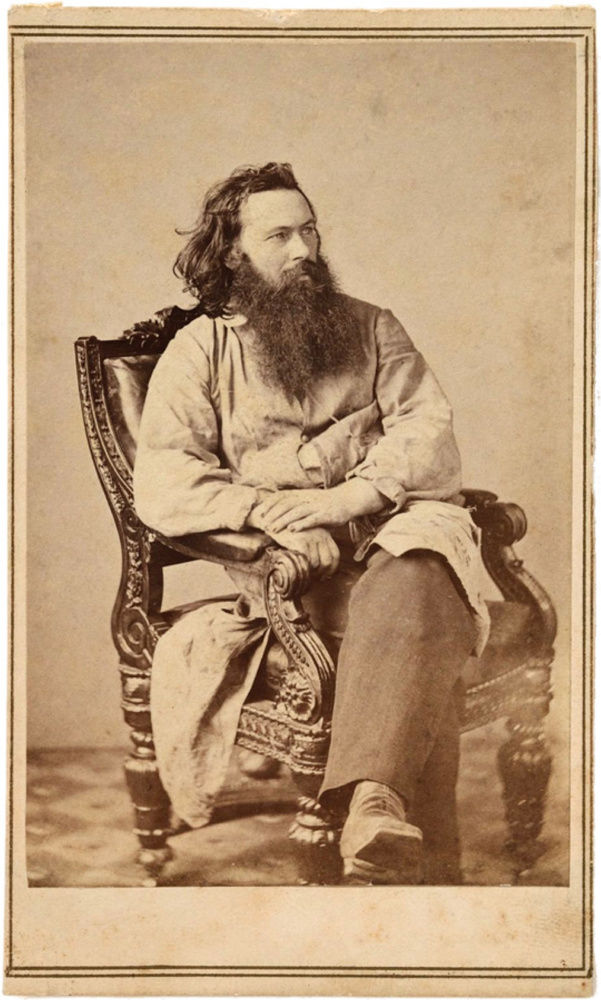

Gardner was born in Scotland and came to the United States in the 1850s. He worked for Brady and became his chief photographer in Washington, D.C. Gardner also was an important figure in art history because he was a pioneer in documentary photography and photojournalism, said Goodyear, who previously worked at the National Portrait Gallery, where he helped arrange an exhibition of Gardner’s photographs.

“While Mathew Brady gets a lot of the credit for photographic documentation of the war, Brady went out on the front lines only on one occasion and was traumatized by what he saw and never went back,” he said. “But Gardner spent a lot of time during the war photographing important battles, landmarks and communities in both the North and South.” He published his work in a photographic sketchbook in 1866.

He became close to Lincoln and took the president’s photo more than any other photographer, Goodyear said. “He was a strong unionist. He was an abolitionist, and he clearly supported Lincoln and identified with his politics,” he said. “Lincoln and Gardner seemed to have built quite a good relationship with one another. Every time Lincoln needed a new photograph, he went down the street and sat for Gardner.”

Ann M. Shumard, senior curator of photographs at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., said the photo is significant because it’s rare and because it captures an important moment in U.S. history. Gardner made his photo during times of tumult. Between Lincoln’s election and his inauguration, seven Southern states voted to secede from the Union. The Civil War began the month after Lincoln was inaugurated.

As he ended his address on that winter day in 1861, Lincoln called for unity. “In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war,” he told the gathered crowd. “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

In that context, this photo is one of the most important in U.S. history, Shumard said.

“The nation at that point was coming apart at the seams,” she said. “Who knew whether this was going to be the last inauguration of a president who would preside over an entire nation? No one could know the future of our country.”

__________________________

CORRECTION: This story was updated at 12:22 p.m. on Jan. 17, 2017, to correct that the photo is one of three known to exist from this event.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story