There is no bolder painter in Maine than Jamie Wyeth. His 18 works in “Jamie Wyeth: Private Collection” on view at the Ogunquit Museum of American Art through Halloween are testament to that.

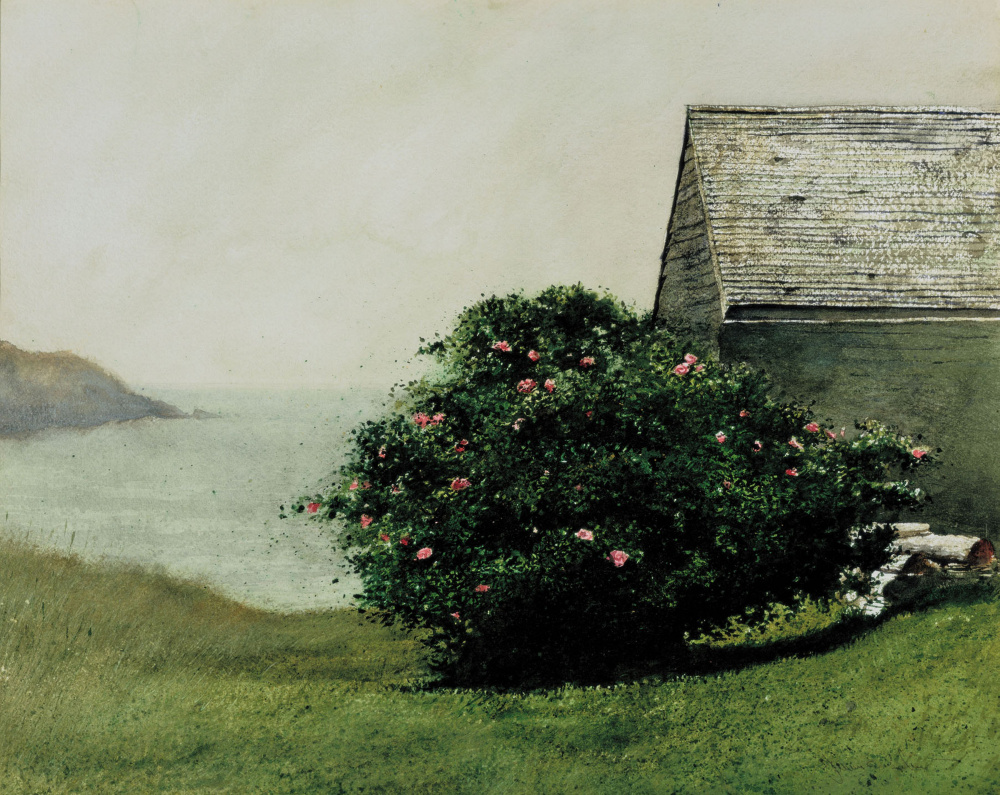

Wyeth’s works include landscapes, portraits and coastal creatures – all normalish enough stuff for Maine, right? And yet there is almost nothing normal about them. Even “Island Roses,” a 1968 watercolor that could tether him to his forebears, feels eminently strange, which is ironic in this case. Here, normalcy sticks out like a sore thumb.

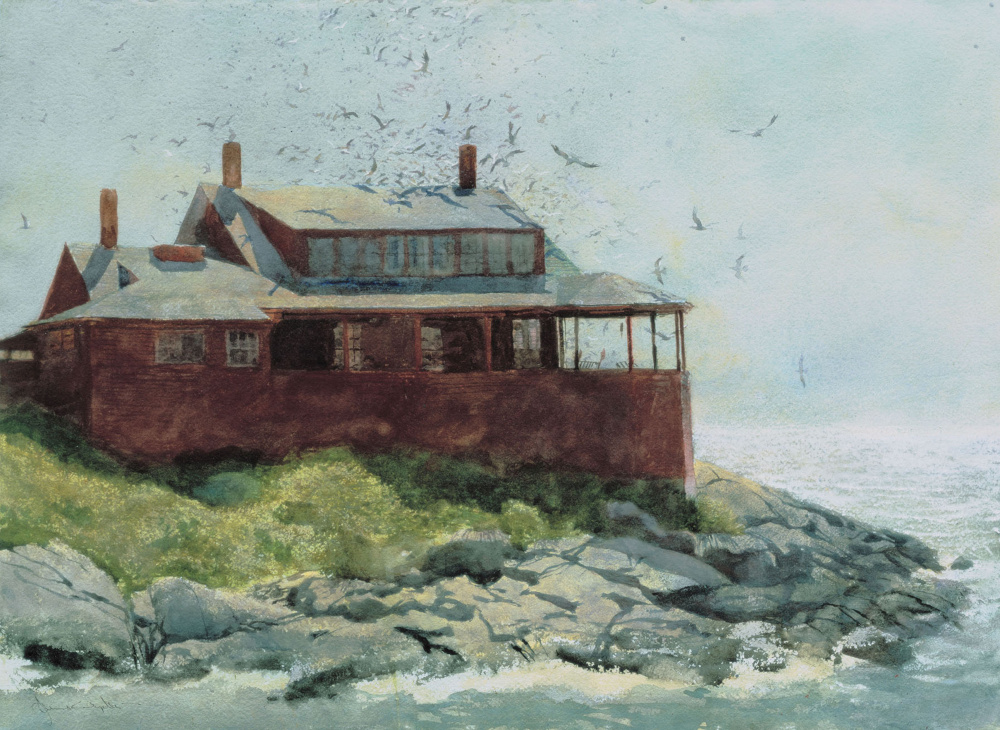

In the older works, the oddities trickle in quietly. In the 1972 watercolor “The Red House,” a swarm of seagulls floats over the home on the ocean’s edge, where effervescence dances over sparkling water. The nicely rendered Homer-esque scene looks common enough but seems a bit off. With the gull gathering, the house seems to be playing the part of a fishing boat pushing through the water, pulling its wake and cloud of chum-seeking gulls behind it.

The 1961 watercolor “Blueberry Field, Olsons” fronts its unbridled creepiness with a dead gull posted on poles in the foreground with the fog-flattened farmhouse looming across the scraggly green field on a gray-white background. Wyeth uses the unsettlingly imagery to hide the casually virtuoso flair of his technique. It’s an image worth mining for painterly passages, but it takes time to look past the sculptural pronouncement, or a quiet mind to take it for what it is.

One of the most remarkably odd aspects of Wyeth’s painting is the role that animals play in his work. The easily-opened door is to consider him an “animalier” – an artist expert of animals like Antoine-Louis Barye (1796-1875) or even James Audubon (1785-1851) – but Wyeth’s interest in depicting animals has more to do with reflecting human subjectivity than examining fauna. His seagull paintings here, for example, relate to his “Seven Deadly Sins” series from about 2004–2008, in which the artist depicted human foibles through seagulls. These are striking images largely because of Wyeth’s technique. In “Peeky Toe” (2001), a gull takes wing with a crab caught by the claw in its beak. We know what will happen next: The gull will fly up and drop the crab on the rocks to kill it and break its shell for meat. The scene itself is rendered in a flurry of chalky white over blazing gold (the light of the sky that covers much of the gull) and chartreuse (the crashing ocean’s spray erupting as the gull leaps). The wine-dark crab is only visible over the black sea by outlining sea foam that throws it into relief. The whole scene is a flash of violence and triumph, white life to the victor and dark death to the tasty prey.

To a certain extent, the narrative is used to set the stage for Wyeth’s flurried execution. The effect connects the artist to the time-constrained plein air painters of Maine and even to wildlife sketch artists, but the deepest connection reaches, however unlikely, to Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732-1806). Fragonard made a series of paintings called “fantasies,” which were executed sometimes within the course of a single hour. (English speakers doesn’t distinguish between paintings as the French do, but these were “ébauches,” or “oil sketches,” as opposed to a finely finished grand painting called a “tableau.”) The best known of these in America is the National Gallery’s “A Young Girl Reading” (1776) and I have absolutely no doubt “Peeky Toe,” with the same orientation and gold/white starring palette, is a direct response to this great Fragonard.

It’s not just the orientation, subject (the fruits of concentration, maybe?), palette or composition that suggest the Fragonard as a model for Wyeth, it is the combination of how marks and the painted ground below them are used. The stroke of genius in the Fragonard is the girl’s right little finger – a single, pink stroke that anchors her gesture, demeanor, her etiquette, her body, and even her social station in a flash of a microsecond. And throughout the Fragonard, we see this kind of elegant economy: Her pillow is fully fluffed with a few frontal strokes of impasto. This is precisely what Wyeth wants to achieve here and in the best of all of his works. He wants the hard parts – the birds’ faces and shapes – to be perfect, but for the rest to pulse with finely controlled energy that uses the bravado top strokes to energize the savvy and light-touched underpainting.

At his best, Wyeth achieves this. And the appeal is the sense of performance. This approach is strategic, but it cannot be reduced to a recipe. Moreover, it is a way to combine the best of classical painting with postwar American performative painting – the subjectivity-soaked approach championed by Abstract Expressionism. For better or worse (it puts a bad taste in the mouths of many), it takes a rare artist to pull this approach off. Jamie Wyeth is one of those rare artists.

Looking back to his 1975 “Islander,” in which a ram looks out over the cliffs to the open ocean, we get a primal sense of territorial mastery. The incredible realism of the sheep’s wool is impressive, but the specificity of its rendering adds an odd tension between a moment in time and the extreme focus that went into its production effort.

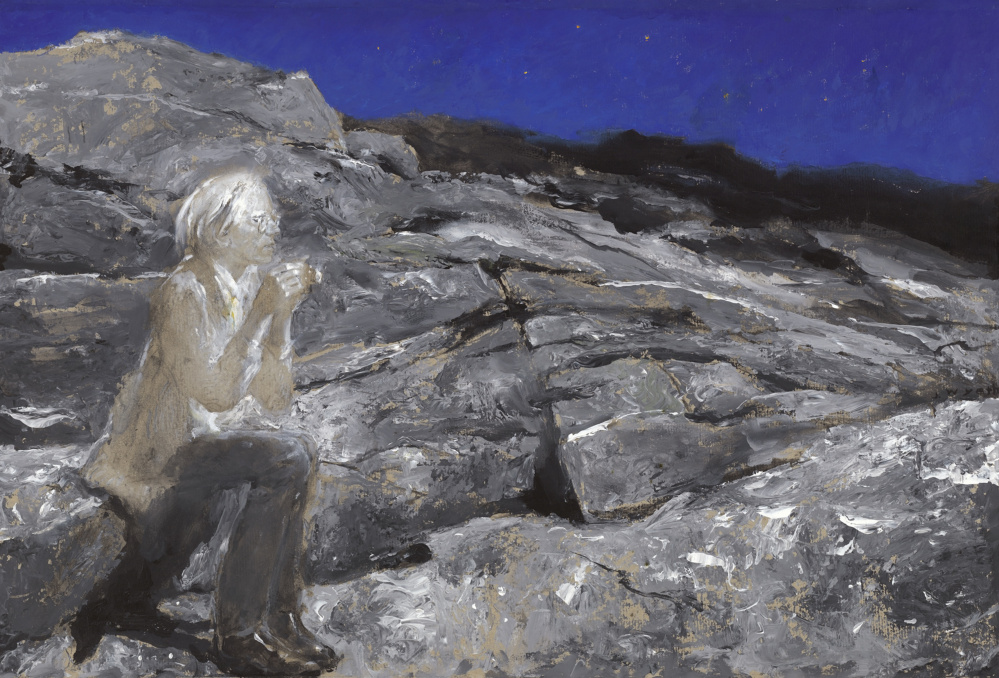

The strangeness of Wyeth’s images of Andy Warhol is a sort of conceptual double-pump fake. What artist could be more different than Wyeth than Warhol? But Warhol and Wyeth were close friends. Warhol invited Wyeth to work in his studio, the Factory, and he often visited Wyeth at his Pennsylvania home. The three images of Warhol alone could have been made anywhere at any time. Riffing on Warhol, they are efficient, unflinching and recognizable. But the final image, “Moonlight Voyeur” shows Warhol sitting on Monhegan, an imagined scene that, like the other Warhol images, was painted in 2012, 25 years after Warhol died. To a large extent, these images open up the subjectivity of Wyeth’s relationship to the past, particularly art history and his personal relationships with several of America’s most historically important artists. We can talk about the influence of his father on his work, but in the end, what about the role of his father on Jamie Wyeth, the person, or the importance that Warhol, his friend, had on his life and the man he has become? Wyeth’s art takes on issues of subjectivity from an ultimately personal perspective, and it takes on the subject of imagination as a way people think of others, how we care about each other, and how we can miss each other.

Wyeth can stand among other great artist and still be himself. He might be the famous son of a famous family, but Jamie Wyeth is one of America’s greatest painters. “Private Collection” leaves no doubt about that.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at dankany@gmail.com.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story