As Mainers prepare to help elect a new president, the Maine Sunday Telegram visited voters in Turner and Hallowell, two comparably sized towns just 35 miles apart, each hugging a major river and adjacent to an important city. One is a bastion of anti-government conservatism; the other is home to the most liberal electorate outside of Portland. Residents of the two towns, which lie in separate congressional districts, describe their communities as tolerant, neighborly, caring and civically engaged, but they come to opposing conclusions about how best to sustain a healthy town, state and nation. The differences help shed light on a growing chasm between the state’s rural interior and the often more affluent communities of the coast and former shipping centers on the lower Kennebec and Penobscot rivers.

HALLOWELL — Betsy Sweet had had enough.

When Gov. Paul LePage announced in August that he was keeping a three-ring binder of drug dealers and that most of those arrested for trafficking in Maine were black or Hispanic, Sweet decided to do something.

Sweet, an alternative healing practitioner, progressive lobbyist, and former head of the Maine Women’s Lobby, organized a rally in front of the State House to call for his resignation. With just 48 hours’ notice, she figured she could get 50 people to attend. Instead, nearly 1,000 showed up, and many in the crowd were fellow residents of Hallowell, the Kennebec river town just downriver from Augusta.

“What LePage did pushed every button I have: I’m a mother of twins of color, I do legislative advocacy, I’ve spent years doing anti-bullying and anti-hate crimes projects, and in my current healing practice I work with addicts and people in recovery,” she explains. “I was horrified nobody was calling LePage on it.”

Sweet, like many others in this eclectic community of artists and politicos, is horrified by the prospect of a Donald Trump presidency for the same reasons. “We’re a community that’s about turning toward someone, not against them,” she says. “I don’t think he represents a single value we have as a community.”

Betsy Sweet, who organized a rally decrying Gov. Paul LePage, poses for a portrait in her living room in Hallowell. Gabe Souza/Staff Photograpaher

Hallowell has, by some metrics, the most liberal voting population in the state after Portland. Created in the late 18th century to be a rival not just to Portland but even to Montreal, this one-time seaport-on-the-river never grew beyond 4,800 residents but has always seen itself not as a rural town but as a micro-city, a center of commerce, culture and the arts and, since the early 1980s, the closest thing to Greenwich Village in central Maine.

It gave LePage’s 2014 opponent, Mike Michaud, his best showing of any municipality in the state, save Portland and the three tribal reservations. In 2014 it was one of just three organized towns that chose progressive Democrat Shenna Bellows over incumbent U.S. Sen. Susan Collins, and in 1990 it elected the first openly gay member of the Maine legislature, Dale McCormick.

“We’re a community that appreciates the role of government,” says former mayor and city councilor Charlotte Warren, who represents the area in the state legislature. “The government is our social contract, through which we work together to have good schools and safe roads, and fire protection and clean water. When people are all sharing a space, there’s a system that is used to make that space better for everybody, and that’s the role of government.”

INVESTED IN INSTITUTIONS SINCE 1791

Hallowell has invested in and relied upon shared institutions since the 1790s, when the grandsons of Benjamin Hallowell arrived on the vast tracts of land their mother had inherited. Charles and Benjamin Vaughan were members of the English gentry; wealthy, highly educated and, in the words of historian Alan Taylor, “smitten with the Enlightenment’s promise that liberally educated men could rationalize human society… disseminating reason among their fellow men.” Hallowell was to be their sandbox.

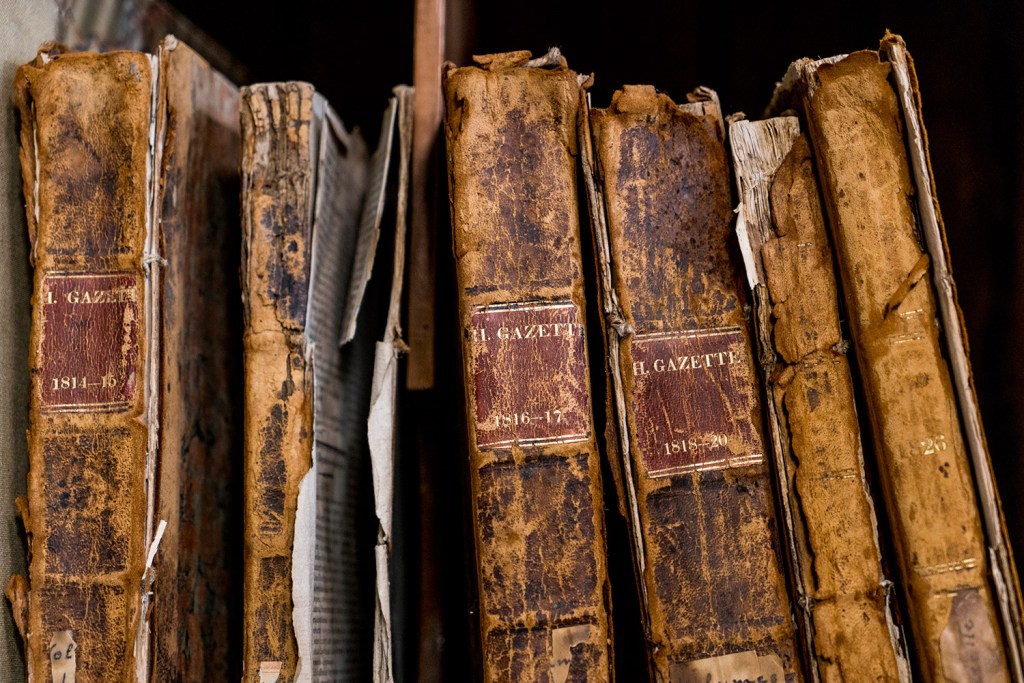

With deep water frontage at the head tide of the Kennebec, the brothers envisioned the village becoming the primary seaport not only for western Maine but for southern Quebec and northern New Hampshire and Vermont as well. They built grain mills, wharves and warehouses; helped plan and finance the construction of a courthouse, jail, academy, teacher training school, experimental farm, and Congregational church, and allowed residents to borrow from their mansion’s library, then the second largest in New England – after Harvard’s – with 10,000 volumes. The 1807 edition of the American Encyclopedia declared Hallowell was “certain to become one of the largest American cities.”

Indeed, by 1820 Hallowell was the busiest place east of Portland, with shipyards, oceangoing ships, a thriving granite and book publishing industry, two newspapers, trading ties that extended to the West Indies, and 2,500 inhabitants, about as many as today. Residents fully expected to become the capital of the newly independent state.

But it lost the capital to neighboring Augusta and, overshadowed, never grew into a metropolis, though its leading citizens continued to invest in civic projects. The Hubbard Free Library, a gothic stone building resembling a diminutive cathedral, was the first public library in Maine in 1880, and its 1898 City Hall – a grand classical revival building with cypress interiors and an elegant auditorium – is well out of scale for a community with fewer people than many cruise ships carry.

The tiny incorporated city shared the downward trajectory of larger urban areas in the mid-20th century, becoming so blighted and moribund by the late 1960s that the city council intended to take the federal government’s offer to bulldoze the entire east side of Water Street in what would have been Maine’s first “urban renewal” project.

“Behind the buildings on the west that were left standing they were going to build small mini-mall type things,” recalls Dick Bachelder, who was mayor at the time and supported the project. “We were desperate. I can’t describe to people how bad it was. The buildings were falling apart, and you could see the sewage floating down the river. The smell was so bad my mother wouldn’t let us open the windows of our house. You just didn’t tell people you were from Hallowell.”

Townspeople, led by some of the early antique shop owners, defeated the plan, as well as a state plan a decade later that would have knocked the riverside buildings down to make way for a four-lane highway. Many cite those events as watershed moments for civic pride and political activism.

“I’m so glad we got defeated,” Bachelder, 89, says of the urban renewal project. “Because within the next 10 years, all the people from away moved in and turned this community around. The old timers weren’t happy about it at all at first, but they came around.”

It started with antique stores selling the remarkable contents of this former global trading port’s attics, then artists attracted by the cheap rents and urban feel, and growing numbers of state workers and lobbyists drawn to the historic homes and impressive river views.

“Slates came along in 1979 and was your alternative food restaurant, attracting a lot of attention and a kind of development in downtown that was different than before, with bars and art galleries,” recalls Frank O’Hara, a community planning consultant who relocated from Portland in 1982.

“It started attracting people who like a feel of urban life, and also became place like Ogunquit where a lot of gay people felt comfortable.”

Geoff Houghton, who opened The Liberal Cup, the popular politicos’ watering hole, in 2000, says the bars and restaurants had by then spawned a lively music scene. “There weren’t that many places in Central Maine to play, so Hallowell became the cool place to be,” he says. “Artists and musicians tend to lean left, so that in turn created a liberal circle.”

Geoff Houghton stands outside the Liberal Cup, his business in Hallowell. Gabe Souza/Staff Photograpaher

As anywhere, there are political differences, but in Hallowell the majority often supports public investments, like when the city council voted to give money to the school system to save language teacher and nurse positions, or to invest $700,000 in a riverfront bulkhead that now supports a popular city park, or to repair the collapsed roof of the public ice skating rink. “Researchers say that to attract people, you need to create a vibrant place where people want to live,” says Warren. “We’ve committed to doing that in Hallowell, so we have the amenities people want, from being able to walk to dinner to trails in the woods.”

IDEA OF TRUMP ‘ALMOST LAUGHABLE’

All this makes Hallowell a difficult place for this year’s Republican nominee. “I’m not sure that Trump is a conservative, but he’s a hater of government,” Warren says. “And in a country that was founded on religious freedom, Trump is saying we should not allow any Muslims into the country. He didn’t say we shouldn’t allow Syrians – so presumably Christian Syrians are allowed – he said Muslims. For my neighbors, the people I talk to at brunch at Slates or listening to music at The Liberal Cup on a Thursday night, that’s just so far from what we believe.”

Sam Shain, a second-generation Hallowell musician and member of the funk band The Scolded Dogs, supported Bernie Sanders, who won the Democratic caucus here by a wide margin. “I don’t care for Clinton’s hawkish foreign policy, for her support when her husband Bill Clinton was being ‘tough on crime,’ and her alignment to Wall Street and fracking,” he explains. “But Trump is concerning to the point where he shows shades of fascism, preying on the fears of possibly less-educated people who are feeling some of the crunch of these economic times that we’re in and taking it out on people who don’t deserve to be seen as the enemy.”

He says many Sanders supporters he knows in town say “Clinton is a great choice too, but I also know a lot of people who are where I am: that Clinton is better than Trump, but that that’s not saying a lot.”

O’Hara agrees that there are a significant number of people in town who are voting for Clinton as a practical matter but without a lot of passion. “It’s a Hillary town, but I think if Bernie had been nominated there would be a lot more younger Democrats being active,” he says. “But they look at Trump and people are sort of numb and in shock. They hear the things he says and then see the polls get tighter.”

Houghton of The Liberal Cup – the name is a reference to generous serving sizes, not politics – says he gets a politically mixed crowd and that in past presidential election years there were more heated debates among the bar’s patrons. “This year, Trump is almost laughable,” he notes. “It’s almost like there’s not a serious discussion. Nobody is pro-Trump, even if some are anti-Clinton.”

Sweet expects a Clinton landslide and traditionally strong turnout in Hallowell nonetheless. “I haven’t heard any of that Bernie-or-bust thing here,” she says. “The prevailing attitude in this town is that we will elect as progressive as we get, but if our option is a little less progressive, we’ll go for it.”

Correction: This story was updated on Oct. 9, 2016, to correct the name of the library in Hallowell and Geoff Houghton’s first name. Captions were also updated to correct the name of the river by the town.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story