A Portland landlord rented out substandard rooms that became “death traps” when fire swept through his apartment building two years ago and killed six young adults, a state prosecutor said Monday.

Survivors who escaped the blaze heard the screams of women who were trapped in third-floor bedrooms because their only way out was a staircase that had been destroyed by the flames, Assistant Attorney General John Alsop said in opening statements of Gregory Nisbet’s manslaughter trial. Alsop said that Nisbet knew about the dangers, but didn’t care.

“All three occupants on the third floor could, and would, have escaped the fire if there was a means of escape, and it was reckless and criminally negligent of the defendant to rent out, permit and allow occupancy of the third-floor rooms, knowing they were essentially death traps in the highly foreseeable event of a fire,” Alsop said.

Nisbet’s attorney, Matthew Nichols, disputed the prosecution’s core argument in his opening statement, saying the apartment building did not meet the city’s definition of a rooming house and therefore did not require additional alarms or fire security. He said the third-floor bedrooms met the definition of a single-family unit. “There is no requirement for blood relation in the city ordinance,” Nichols argued.

Nichols also suggested that the fast-spreading fire and noxious gases – not the condition of the building – may have prevented the victims from escaping.

Nisbet told a fire investigator that he provided the third-floor residents with a rope ladder as a secondary way to get out of the unit in an emergency, according to testimony Monday.

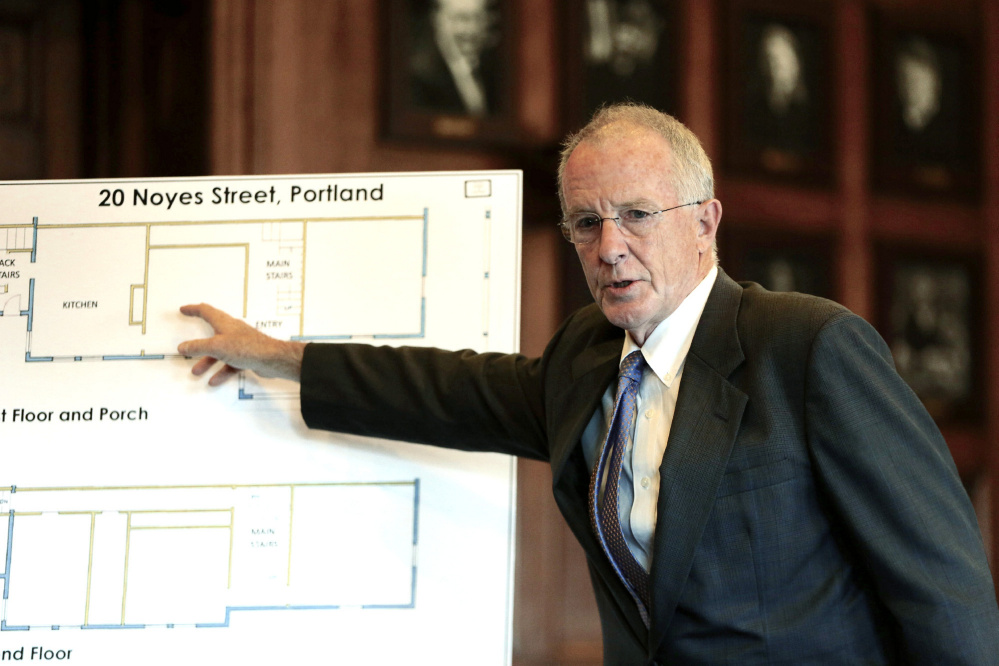

Nisbet faces six counts of manslaughter stemming from the fire at 20-24 Noyes St. on Nov. 1, 2014. Five of the victims died inside the building, and the sixth ran through flames engulfing the front door and died days later from his burn injuries.

Nisbet could face a long prison sentence if he is convicted. He would be the first landlord in Maine convicted of manslaughter in the death of a tenant because of negligent operation of a building, according to the state Attorney General’s Office.

Manslaughter – defined as recklessly or with criminal negligence causing someone’s death – is punishable by up to 30 years in prison and a $50,000 fine.

Nisbet also faces five misdemeanor charges of code violations.

The fire was ignited by improperly discarded smoking materials on the front porch and was fueled by a chair and a couch on the porch. Investigators say the building’s smoke alarms were not working and a rear stairwell was blocked by furniture, forcing the three survivors to jump from a second-story window.

The fire killed Steven Summers, 29, of Rockland, Maelisha Jackson, 23, of Topsham and Chris Conlee, 25, of Portland, who were visiting the house, and David Bragdon Jr., 27, Ashely Thomas, 26, and Nicole Finlay, 26, who were residents.

The trial is being watched closely by the families and friends of the six victims, some of whom got emotional in the courtroom Monday when Daniel Young, a senior investigator for the state Fire Marshal’s Office, walked the judge through the fire investigation.

Using a series of photographs displayed on a flatscreen TV, Young described the locations, positions and conditions of the bodies. The photos could not be seen from the back of the courtroom, where the families sat.

Family members declined to comment as they left the courthouse Monday.

The trial also is being watched by the larger community, including landlords who say that the blame is misplaced and that the charges set a bad precedent.

In his opening statement, Alsop painted Nisbet as a careless landlord who had little regard for his tenants and was neglecting the property.

He said Nisbet bought and renovated the house in 2003, and stopped paying his mortgage in June 2011. Foreclosure proceedings began the following year, with a judgment of foreclosure entered in July of 2014. Nisbet had until Dec. 3, 2014, to reclaim the property by paying his mortgage, Alsop said.

Meanwhile, Nisbet continued to rent out the building and deferred maintenance, Alsop said. Tenants had no leases, after the most recent lease for 24 Noyes St. expired in August of 2011, he said.

Alsop said that Nisbet was renting out individual rooms and that investigators found that tenants had put locks on the outsides of their doors, prompting investigators to conclude that the building was being operated as a rooming house.

“He lives on the same street,” Alsop said. “He knows there’s excessive smoking on the porch. He knows there’s a buildup of flammable materials on the porch. He knows there is no fire safety equipment in the house. And he knows there’s an ever-changing list of occupants that is in no stretch of the imagination a family. He knows there is no lease. He knows the third-floor windows are hopelessly inadequate as fire exits and death is a certainty in a fire, but he doesn’t care.”

Alsop added: “The only thing he appears to care about is coming by on a monthly basis to pick up the rent.”

Nichols disputed the prosecution’s claim that the building was a rooming house.

The defense attorney said Portland city code defines a single-family dwelling as up to 16 people living in a unit. It does not require those tenants to be related to one another, because the Maine Human Rights Act prohibits landlords from asking such questions, he said.

Each side of the duplex had a house leader responsible for collecting the rent from other tenants, Nichols said, and Nisbet was typically given the full rent all at once, rather than having individual tenants pay him.

“The use of the building is important for the court to determine,” he said. “If it’s determined to be a boarding house, it has a longer list of life-safety prevention devices that are required.”

Nichols also asked the court to pay attention to the speed of the fire and when the victims may have become incapacitated, though he did not reveal much about how those points would shape his argument.

The building did not have operating smoke detectors.

Young, the state fire investigator, said one smoke detector was found on top of the refrigerator, still chirping from a dead battery. Detectors in the second-floor bedroom were missing, with only wiring hanging from the ceiling.

The apartment building also lacked the required fire doors, which can slow a fire from spreading, he said. Damage was so bad that the third-floor bedrooms had to be accessed by cutting through the walls at 24 Noyes St., which sustained less damage.

Young said he met Nisbet on the day after the fire. Over the course of an hour-long conversation, Young said, Nisbet admitted that he had not been inspecting the apartment and typically collected the rent on the porch rather than inside the building.

David Sheppard from the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Firearms, Tobacco and Explosives fielded questions about a computer model showing how quickly the fire, heat and noxious gases spread through the house. It took less a minute from the time that Summers opened the front door to escape for the heat and gases to reach the third floor, he said.

Summers sustained severe burns when he escaped and died three days later in a Boston hospital.

The trial will resume Tuesday with testimony likely coming from survivors, past tenants and a building contractor, Nichols said after court adjourned for the day. The trial is expected to last one week.

Nisbet waived his right to a jury trial, so his fate will rest with Superior Court Justice Thomas Warren, an 18-year veteran of the bench.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story