Kate Furbish was a little woman. Her health wasn’t great. Born in 1834, she was raised by parents who owned a hardware store in Brunswick, but she never married; naturally, given the era, this limited her financial resources.

She had sharp eyes though, an eager capacity to learn and the kind of endurance that took her all over the state, from the Crown of Maine to the bogs of Bangor and east to Cutler. By train and by horse-drawn carriage and most important, by foot, Kate Furbish traveled her hometown of Brunswick and then onward, over the state of Maine looking for flowers she’d never seen before. She was an intrepid collector and painter of specimens and in her mid- to late 40s was at the forefront of botany in the state despite having no degree in plant science.

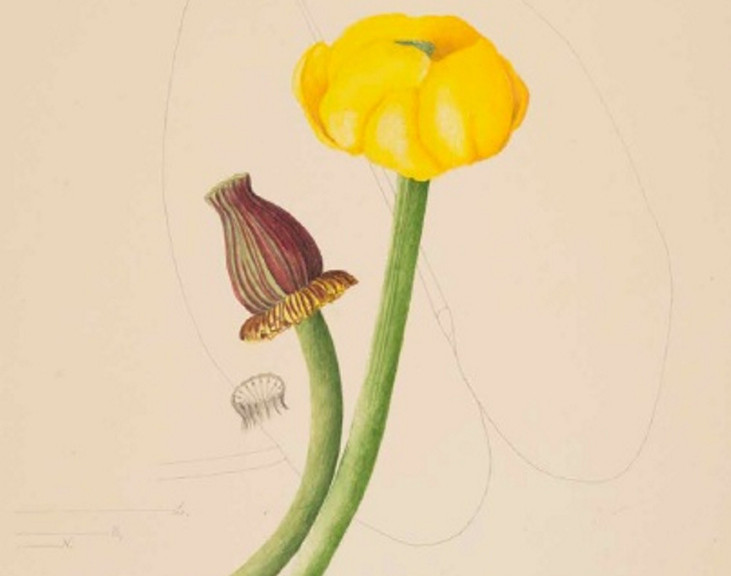

After nearly four decades of intense work, almost all of it as a volunteer, save her a stint in the 1890s as the staff botanist at the Poland Spring House, Furbish completed 1,326 paintings and sketches of the flora of Maine. When she gave them to Bowdoin College in 1908, bound in 14 Moroccan leather volumes, she claimed no “artistic merit” in a letter to Bowdoin President William DeWitt Hyde, only “truthful representation” of the plants she’d found around the state. Her hope, she wrote to him, was that her paintings “will assist the earnest student instead of serving merely to entertain the visitor…”

That was her modest wish. The paintings were her “children” she joked, or half-joked – her letters suggest a wit as sharp as those eyes – and she kept just one for herself.

She lived until 1931 having no idea that her work would alter Maine environmental history or of the spell of intrigue it would cast over a unique group of individuals over the next century and beyond: an artsy Bowdoin student in the Vietnam era; a pair of Milbridge writers and naturalists in the 1980s; then in the next decade a psychotherapist from Washington, D.C., and a young woman getting a master’s degree in botany from the University of Maine who now runs the education program at the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens.

37 POUNDS OF LOVE

Furbish has had her moments of rediscovery before, including most recently in 2013 when a 600-acre parcel of waterfront land on the former Naval base in Brunswick was named the Kate Furbish Preserve. But she’s never had a vanity moment quite like this. The latest installment of Furbish fever is a gigantic book, or rather, books, titled “Plants and Flowers of Maine: Kate Furbish’s Watercolors.” This two-volume set is destined to tax most coffee tables, weighing in at a solid 37 pounds and possessing roughly the dimensions of a jumbo cookie sheet. The publication is a joint effort of Maryland-based Rowman & Littlefield and the Bowdoin College Library, in collaboration with the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens. The editor of the two-volume set is Richard H. F. Lindemann, who was the director of Bowdoin’s archives for 15 years (he retired in 2015).

But the seed of it was planted not long after Jed Lyons, the future president and CEO of Rowman & Littlefield, arrived at Bowdoin in 1970.

Lyons was a cartoonist while at Bowdoin and published in the school’s newspaper, the Bowdoin Orient. The college didn’t have much of a studio art program at that point, so it wasn’t Lyon’s major. But art remained an interest, and maybe a bit of a distraction during study sessions at the college’s library.

“When I would get bored I would go up to the Special Collections room where the Audubon prints were,” Lyons said. Bowdoin has a complete set of John James Audubon’s “The Birds of America,” one of what’s believed to be only about 120 in the world. “There was always an Audubon out. The same was true with Furbish’s paintings.”

He admired the paintings, and perhaps even more so, the woman who had devoted her life to making them. “She worked independently, and her equipment always included grappling hooks,” he marveled. “She would crawl on her stomach to get to a plant.”

In an era when publishing houses have generally been on the decline financially, Rowman & Littlefield, known for its academic and museum studies books, has been making money and growing. (In 2013, the company acquired Maine’s own Down East Books.) And Lyons never forgot those Furbish paintings, or the botanist who had something of that Audubon-like urge to be a completist and paint every one of Maine’s flowering plants.

“I reached out to Bowdoin and I said ‘These really need to be collected in a book and seen by more than just a handful of people every year,’ ” Lyons said. The college loved the idea, he said, and this month marks the release of the Furbish sets, priced at $350.

“It is, needless to say, a very expensive undertaking,” Lyons said. “That’s a very expensive trim size and yet every one of those paintings is reproduced exactly as she drew them. We decided right off the bat that if we were going to do this, it was going to be done right.”

He is not expecting to make money, despite the price tag, since the volumes are likely to appeal to a limited crowd: academic libraries, collectors and those with an interest in Maine horticulture. An even more deluxe version, with leather binding and hand-colored end sheets, priced at $750, already has eight pre-orders from Bowdoin alumni, he said.

TRIUMPH OF THE LOUSEWORT

When Bowdoin celebrates the Furbish book launch with a reception at the library on Sept. 26, the guests will include Ada Graham and Frank Graham Jr., the Maine couple who wrote the only biography of the botanist. She’s 85 and he’s 91. Their book, “Kate Furbish and the Flora of Maine,” was published in 1995 by Tilbury House, representing the culmination of a nearly 20-year fascination that began with the environmental controversy over a type of wild snapdragon discovered by and named for the Brunswick-based botanist, the Furbish lousewort (Pedicularis furbishiae).

Furbish found the lousewort in 1880 alongside the St. John River. She’d traveled north via Orono, taking a train to Mattawamkeag and then on to Fort Fairfield by stagecoach (in a letter, she noted that often a carriage to the County included a gun on the seat next to the driver). She spent six weeks there, exploring the land near the Aroostook River looking for plants she’d never seen before, including those identified by Saco native botanist George Goodale (who was serving as first director of Harvard’s Botanical Museum) in the 1860s. She continued north, arriving in Van Buren in August. The Grahams describe her as going right to the banks of the river where she was pleased to see plants she’d never encountered before. One looked a lot like the common lousewort, but not quite right, and she jotted down “new species?” in her notes. When the summer was done it proved to be something not only new to her, but to the world of botany.

She sent samples of it and wrote to George Davenport, an avid member of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society and New England Botanical Club who published articles on ferns throughout his lifetime, that winter, with a request. “If Pedicularis sh’d prove to be an unknown species couldn’t it be named for the finder, with propriety?”

Davenport took the hint and pushed his colleagues to name it after Furbish, rather than for its river location. “Miss Furbish has devoted all of her leisure time for a number of years to illustrating the Maine Flora by a series of plates carefully drawn and colored directly from the plants themselves.” Her paintings, Davenport wrote, “are marvels of accurate coloring and fidelity” and her work “one of which any state might feel proud.”

He won out, and Furbish had her own flower, albeit it one with an ungainly name (the generic lousewort originally got its name because people believed – wrongly – that cattle that grazed near it got lice).

Fast forward to the early 1970s, to that same era when Jed Lyons was killing time in the Bowdoin library. That’s when the energy crisis reignited interest in a plan first proposed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1959 to build a hydroelectric plant in the Upper St. John watershed. It had evolved into the Dickey-Lincoln School Lakes Project, a double dam, starting with one just above the confluence of the St. John with the Allagash River. The two projects would have flooded 88,000 acres and changed the landscape forever.

In the summer of 1976, the Corps of Engineers hired University of Maine botany professor Charles D. Richards to survey the area for rare and endangered plants. No one had recorded a sighting of Furbish’s lousewort since 1946 and the plant had been listed as “probably extinct.” Richards found it in Allagash, in the area that would be flooded, and the next summer, not far away in a region downstream. Theoretically, the Furbish lousewort might have survived the Dickey-Lincoln project in that downstream location, but Richards’ findings contributed to the conservationists’ argument against the dam, and the Furbish lousewort was forever linked with the dam and the eventual demise of the project in the early 1980s.

Courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library

BOLD BIOGRAPHERS

The story of the lousewort also awakened Graham’s interest in Furbish. Frank was a field editor for Audubon magazine when the dam was proposed and Ada wrote natural history books for children. They approached an editor in New York with a book idea about the role the lousewort was playing in this modern project. “She said what would be more interesting to her would be a biography of Kate Furbish herself,” Ada Graham remembered.

As biographers, the Grahams had the good fortune of being on time, barely, to get help from Furbish’s grandniece, Alice Furbish Kerr, who had Furbish’s letters to her cousin Millie, which shed greater light on the woman herself – and early feminist, if unnamed as such – than her later botanical-related correspondence. (Of a gentleman caller in Brunswick in the Civil War era who failed to come around for repeat visits, Furbish wrote “I know one thing. Though he was quite pleasant, his company was not essential to my happiness.”)

The Grahams found a journal of Furbish’s from a visit to France, and they pored over every letter in Bowdoin’s possession, including the one where Furbish reveals that the Acadians had dubbed her “the Posey-Woman” in her summers in Aroostook County. “We were like terriers,” Frank Graham said. “Anytime we ever got a sniff or a thought of anything we would follow up on it.”

But the Grahams also had some bad fortune; when their manuscript was complete, the imprint that was going to publish their Furbish book had gone under. They tried to find a new publisher but no one wanted their book about a spinster botanist from Maine. “The manuscript just lay there for seven or eight years,” Ada Graham said.

Enter the next person with a yen for Bowdoin’s Special Collections. Judith Falk is a psychotherapist in the Washington, D.C. area who has a summer home in Damariscotta. In 1977 she went canoing on the St. John with the Audubon Society, the year the Furbish lousewort’s found its greatest fame. Two of her daughters went to Bowdoin and like Lyons, Falk had seen Furbish’s drawings in the library. After an exhibit of the drawings in 1991, Falk told a Bowdoin librarian there ought to be biography of Furbish and was told there was, it just wasn’t published. She got in touch immediately.

“Ada told me, ‘I was just going through my things, and I was about to throw it all away!’ ” Falk said.

Falk drove to Milbridge to have lunch with the Grahams (Ada’s crabcakes were divine, she said) and left with the manuscript. “They said, ‘We’re not willing to change one word.’ ”

“I stayed up all night and read it,” Falk remembered. “It struck me as the kind of thing that would be in the New Yorker.”

She ultimately helped fund its publication in 1995. Tilbury printed 3,000 copies, including 750 hardbacks, which sold out immediately, Falk said.

BIRTHDAY PRESENT

In 1996, when Melissa Dow Cullina was a graduate student at the University of Maine, studying botany, she took a trip to Fort Kent with the Josselyn Botanical Society. The society was founded in 1895, and its charter members included Furbish and Merritt Lyndon Fernald, a native Mainer and close friend of Furbish’s who had the career she might have had if she had been born a man. (He started working at Harvard’s Gray Herbarium at age 17 and went on to be an editor of Gray’s Manual of Botany.)

On the trip Cullina saw Furbish’s lousewort and learned about Furbish for the first time. A few months later, her mother gave her the Graham’s book for a birthday president.

“Randomly,” Cullina said. “But it was a perfectly timed gift.”

Cullina, who wrote the introduction to the two-volume Furbish set in her capacity as Director of Education at the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens, fell hard for Furbish. She tries, she says, to emulate Furbish in all that she does.

“One of the things that is so remarkable about Kate is how she did travel, so extensively, throughout Maine,” Cullina said. “If you think about that period of time, traveling by train and carriage and foot, just the amount of energy it required, that in itself is so impressive to me. She didn’t just stay in Brunswick and do what was easy for her. She really traveled outside the box.”

It’s particularly remarkable if you consider that Furbish suffered from neuralgia, a painful nerve condition. It did slow her down sometimes.

During the Civil War, she wrote to her cousin of her longing to go be useful in the war effort. “I would I were a strong rugged woman. B. (Brunswick) would not hold me long I assure you.” Even so, after she discovered her passion for collecting and capturing the unique characteristics of Maine’s flowers, she did not let Brunswick hold her long.

Although Furbish was considered an amateur, having no degree in botany or employment as a botanist (except those seasons at the Poland Spring House, which the Grahams wrote may have been in exchange for room and board), it’s not the right word for who she was, Cullina said.

“I just don’t feel that it does justice to the level of seriousness she applied to her work,” Cullina said. These weren’t just pretty paintings. Furbish, she said, “was a botanical illustrator, a scientific illustrator.”

Cullina already used Rowman & Littlefield’s versions of Furbish’s images in a class at the botanical gardens late this summer. They hold up, she said, as teaching materials.

This new two-volume set is, “a real fulfillment of her vision and purpose,” she said. “It is sort of difficult to think of these beautiful drawings being in storage, so I see this as just a giant leap forward, because they will be available for more people.”

“I hope somewhere she can know that her purpose in creating them is really being fulfilled,” Cullina said.

Which is all Furbish wanted when she made her gift. She signed off her letter to the Bowdoin president with that hope that her work would prove useful to students.

In that case, she said, time might prove that “Love’s Labor (is not lost)…” Between the student who went on to be a publisher, the special collections librarians who cared for the paintings over all those years, the biographers who refused to change a word, the psychotherapist who thought Furbish deserved more and the student who went on to be a teacher, that wish has been granted.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story