Noriko Sakanishi was scheduled to have a solo exhibition up now at the June Fitzpatrick Gallery. Instead, this slot in Fitzpatrick’s schedule went to “Finale,” the final show the gallery owner will give before retiring. It is fortuitous, because Sakanishi has been showing with Fitzpatrick since 1992, the year the gallery opened on High Street.

As anyone who knows Fitzpatrick would expect, the balance of Sakanishi’s 10 works with a casual survey of artists who have shown at the gallery is superb. The installation is spare and crisp. It looks to Sakanishi with focus but opens to a storied past without pretending to be encyclopedic.

Fitzpatrick has operated four Portland spaces over the years, most recently the gallery in the Congress Street space owned by the Maine College of Art. She refined her gallery approach into a contemporary style that combines several recognizable qualities with a few surprising eccentricities, to such a degree that she has few peers across the country. For starters, Fitzpatrick, as her relationship with Sakanishi illustrates, has been faithful and supportive of her artists. Many in this last show have been with her for many years, including Paul Heroux and Alison Hildreth, who is represented by two superb archaeological map-like paintings.

Heroux’s vessels and chargers, joined by works of Lynn Duryea and Sequoia Miller in MECA’s main window, are reminders of Fitzpatrick’s long history of showing ceramics, most notably in a regular, though always extraordinary, December show of works in clay.

Among Maine galleries, June Fitzpatrick has long been the leader in contemporary art, particularly for abstraction. This is why her consistent ceramics shows are so interesting when trying to understand what has made Fitzpatrick’s gallery so identifiable and unusual. Fitzpatrick has an eye for old-school modernism and a penchant for intelligent art objects. She began, after all, as a dealer of drawings, arguably the brainiest neighborhood of the art world.

Objects matter for Fitzpatrick, and we sense her sensibilities in the gorgeous abstract painted panels by MECA professor and relative gallery newcomer Michel Droge, as well as in Jeff Woodbury’s old roadmaps under Lucite made fascinating and gossamer by the artist’s razor reduction of them until they became wispy webs of roads. The same can be said of Sakanishi’s beautifully crafted wall sculptures and textile logic-driven drawings (you say collages, I say drawings; let’s call the whole thing off), Kimberly Convery’s elegantly detailed gouache and graphite skyscrapery gem, Greg Parker’s dark chocolatey striped and gridded panel, Lynda Litchfield’s gameboard-savvy and playful paintings on compact clementine crates, and Sara Crisp’s nuanced encaustic square, circled within and centered by a phalanx of acorn caps.

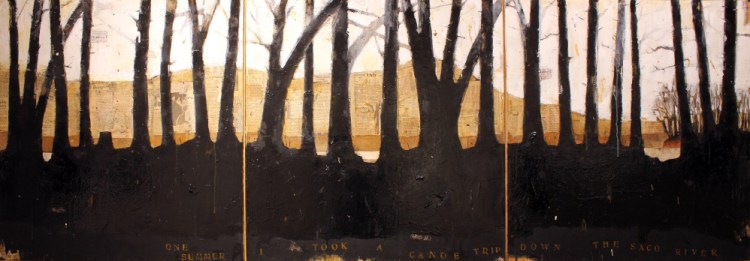

I think of Tom Hall as a Maine painter unsurpassed in terms of power, content and impact, but even Hall’s paintings, under Fitzpatrick’s curatorial gaze, prioritize their (modernist) object qualities: In “Pleasant Mt.,” we revel in his heavily varnished collaged newspaper surfaces spread frosting-thick with white skies seen through solid black forests. Hall’s words across the bottom, sparse as they may be, take the triptych farther from image to document: “One summer I took a canoe down the Saco River.”

Fitzpatrick’s eye for contemporary art that has the feel of sophisticated craft may have old-school roots, hers is an unusual model. It was quite rare even in New York galleries, and where it did appear, it had West Coast associations, like with Charles Cowles, who, while a curator at the Seattle Art Museum, was the leader in showing glass art as contemporary art in the museum’s “Northwest Annual.” In his New York gallery, Cowles showed cutting-edge contemporary work along with high craft artists like Howard Ben Tre, Toshiko Takaezu, Dale Chihuly, Manuel Neri and others. This model has become more influential and more common, and so we must consider Fitzpatrick not only important for contemporary art in Maine, but as a prescient gallerist on a much broader level.

Fitzpatrick is retiring. She is 78. But her seasoned sensibilities are echoed in her artists. There has been talk about Fitzpatrick treating her artists as though they were her children, but in fact the core of her stable leans toward savvy and seasoned rather than the flitting and fleeting flavors of youth. “Contemporary” art, for Fitzpatrick, has long been the stiff stuff for grownups: not the kids table.

Here in Maine, Fitzpatrick’s model – object- and abstraction-oriented art with deep modernist roots, breathably presented – is shared by Duane Paluska’s Icon Contemporary in Brunswick. Also unusual is the fact that both galleries do not keep much (if any) work by other artists on hand and neither has ever had a website or social media presence worth mentioning. Yet these galleries paved the road for what we now see blossoming in Rockland and Portland: a truly robust and worthy contemporary art scene.

One interesting testament to Fitzpatrick’s depth of engagement is the inclusion of an oh-so-delicious big sky landscape photograph by Tanja Hollander. Fitzpatrick never showed photography, so Hollander never had a regular show at the gallery. However, Hollander, who gained international note with her “Are you Really My Friend?” Facebook project, became close to Fitzpatrick and her photo belongs in this show. (Longtime Maine curator Bruce Brown noted in a touching address at the closing party that he treasures Hollander’s Facebook project portrait of Fitzpatrick – which he owns.)

I’ve heard a whole bunch about how the sky is falling with the exodus of Portland’s doyennes Fitzpatrick and Peggy Golden, who recently sold Greenhut Galleries, which she opened in 1977, but everywhere I look, I see their irreversible accomplishments and the artists (and collectors) they have helped grow. I can’t unsee the art I’ve taken in at June Fitzpatrick Gallery. On the contrary, what I have seen at the gallery has grown my eye and strengthened my sensibilities. All that good, for me and so many others, cannot be undone.

And, for this month at least, June Fitzpatrick Gallery is still – as it has always been – absolutely worth seeing.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at dankany@gmail.com.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story