A 60-room motel in East Boothbay is closing its doors for the season nearly two months early because it can’t find replacements for workers who have left.

Sunset Beach normally operates from early May to early October, but last week the owner sent out an email to guests with reservations saying the motel was closing on Aug. 16 “due to circumstances beyond our control.” The email said the motel’s management had contacted another hotel nearby, which said there are rooms available on most days for those guests looking to re-book their stays.

While extreme, the situation Sunset Beach found itself in this summer reflects an increasingly tight labor pool for Maine’s tourism industry. An abundance of new hotels and eateries coupled with a state unemployment level below 4 percent and restrictions on visa programs have wreaked havoc on what is commonly called Maine’s largest industry.

Sunset Beach’s general manager, Alyssa Bouthot, said in an email that the motel started the season short-handed, and the situation got worse when the on-site manager and two housekeepers left at the end of July. The management worried that guests would be upset if the hotel couldn’t clean rooms promptly and if there was no manager on site to deal with any problems.

She said the motel’s management didn’t even try to replace those workers.

“We knew it would be futile and made this decision to close in the best interests of our guests,” Bouthot wrote. She said the motel has plans to hire a new manager and will work with a local employment agency to make sure it has enough motel and restaurant workers when it reopens next year.

Greg Dugal, executive director of the Maine Innkeepers Association, said the decision of a motel to close is extreme, but many businesses in the hospitality industry are struggling to find enough workers in a state where most people are employed, and travel and tourism is experiencing an up year in a rebounding economy. The squeeze is compounded because Maine has little in-migration and an aging population.

“The need is great at every level,” Dugal said. “And it’s not just housekeepers or line cooks, it’s everything.”

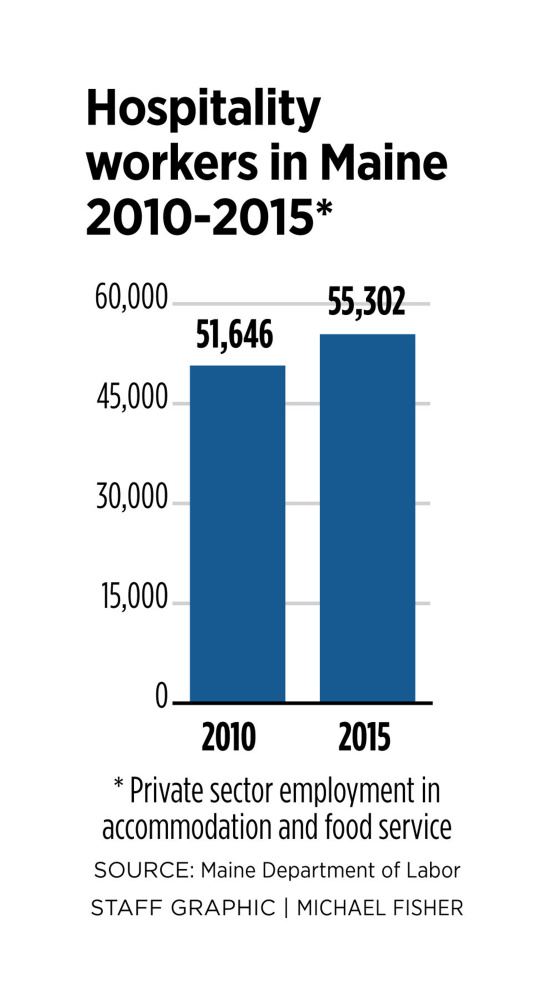

According to data compiled by the Maine Department of Labor, the number of people working in the accommodation and food service industry grew 7 percent in the five years from 2010 to 2015 – from 51,646 to 55,302 – reflecting the growth of hotels, restaurants and other businesses related to the hospitality industry.

CHANGING VISA PROGRAMS

Dugal said larger companies have successfully used a visa program that allows temporary workers to come to the United States for six months. In some cases, those visas can be extended twice, he said, and workers might work for a ski resort in the winter and then return to a summer job.

Last year, a problem with the H2B visa program caused problems for employers in the hospitality industry. The federal government rewrote the rules – for example, imposing stronger requirements that employers attempt to recruit local workers and a new way to calculate a region’s prevailing wages – in late spring. That caused some delays in the recruitment and arrival of foreign workers for summer jobs in the U.S.

Another program, called J1, is a cultural visa that allows foreigners, primarily students, to come to the U.S. to work, but it’s good for only four months, Many hospitality employers that use J1 workers have problems putting together a full staff in the spring or after Labor Day.

Dugal said he doesn’t have any current numbers, but in the past, about 2,000 workers have come to Maine in the summer through the H2B visa program, and probably another 2,000 under the J1 visa program.

Sante Calandri, who owns Ports of Italy restaurants in Boothbay and Kennebunk, said some of the rules for the J1 program have changed, making it more difficult to hire workers with that visa. He said in the past, workers with those visas could work two jobs, but now they are allowed to have only one.

He said it was common for him to hire workers with J1 visas as busboys and dishwashers. When they could also work another job, it made the prospect of working in the U.S. more lucrative.

Vladimir Barlov fills carafes at the Ports of Italy restaurant in Kennebunk. Greg Dugal of the Maine Innkeepers Association says many seasonal businesses are struggling to find enough staff in a state where most people are employed, and travel and tourism is experiencing an up year in a rebounding economy. Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

AWAITING ‘GENERATION Z’

In his Boothbay restaurant, Calandri said he’s been able to hire local people as waiters and waitresses. Those jobs are more popular because workers can earn far more at them.

But even those jobs are difficult to fill at his new restaurant in Kennebunk, he said, because of a local seasonal labor shortage.

Glenn Mills, an economist with the Maine Department of Labor, said the reasons for the labor shortage are familiar: Maine has the oldest median age in the country and many workers are leaving the labor force as they retire. Few people are moving to the state, he said, and young people – who often fill jobs at restaurants, hotels or other tourist-related businesses – are leaving for college and beyond.

That means that during the times when there’s traditionally a labor crunch, particularly the summer, it’s becoming increasingly difficult for businesses to hire enough workers.

“Each summer, the labor market is a little tighter than the year before,” Mills said, and that’s particularly true in smaller communities, like those on the midcoast, far from Maine’s three urban areas.

“On a statewide basis, unemployment is very low and in those coastal tourist communities, it’s been difficult for many (employers) to find staffing for several years,” Mills said. “We don’t have the workforce growth at a time when the labor market is quite tight.”

Dugal said for many employers, the long-term solution is generational change. He said many are waiting for “Generation Z,” generally considered those who were born in the early 2000s, to reach working age.

“But they’re in their early teens and not here yet,” he said. “You just have to tough it out.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story