WATERVILLE — Other than the marks of the artist and the story he tells with the sharp point of his etching tool on a copper plate, there is little tangible evidence that the dozen or so prints arrayed on a table in an art-study room at the Colby College Museum of Art, loosely matted and unframed, are among the rarest in modern art.

The prints were made by Spanish artist Pablo Picasso in France in the 1930s as a commission for the art dealer Ambroise Vollard. This spring, Colby College acquired a full set of the Vollard Suite, 100 signed prints in all, and will display about 60 of them beginning Thursday in “Picasso: The Vollard Suite,” on view through Aug. 21.

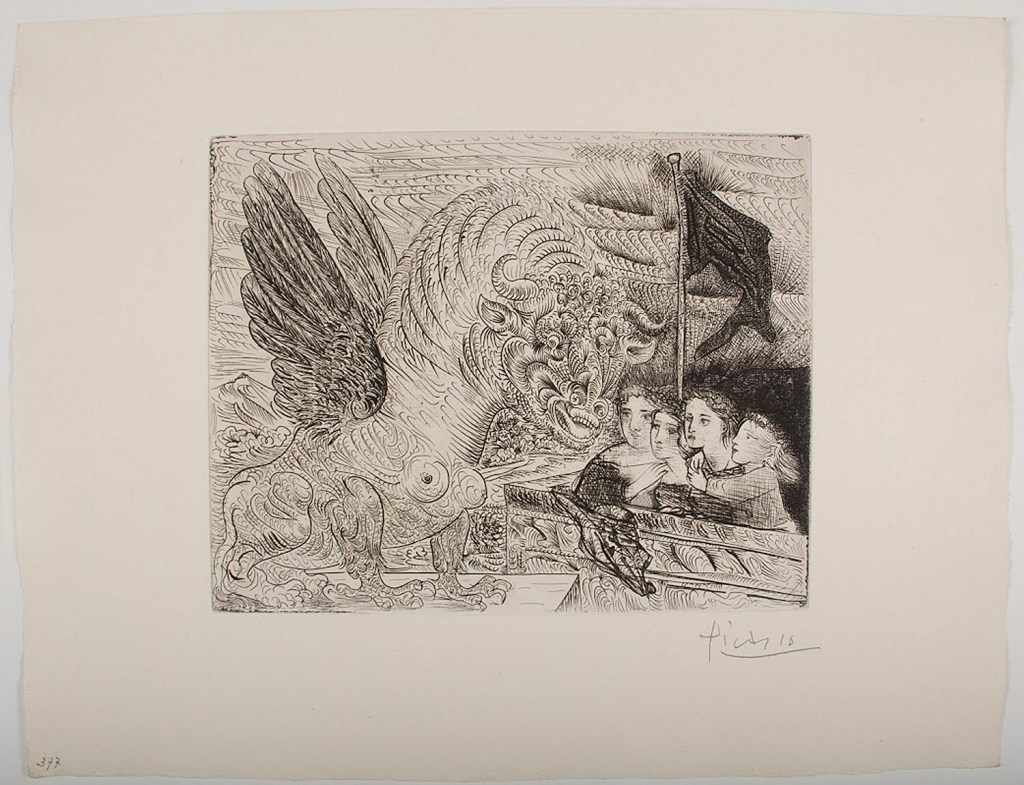

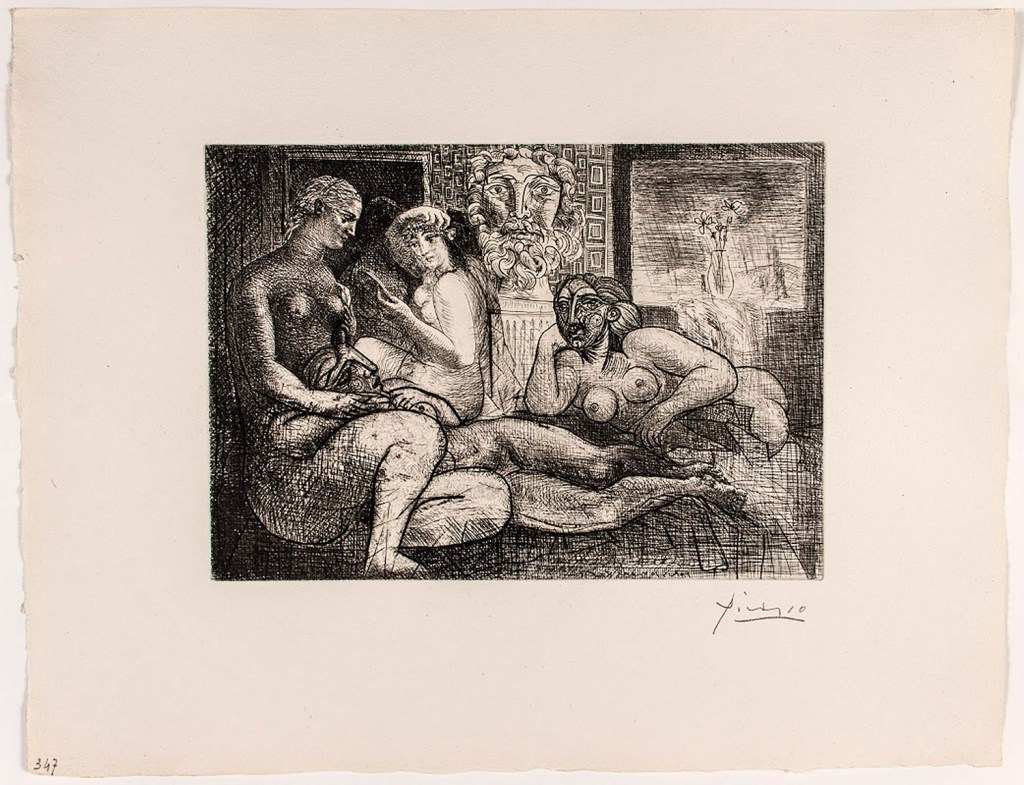

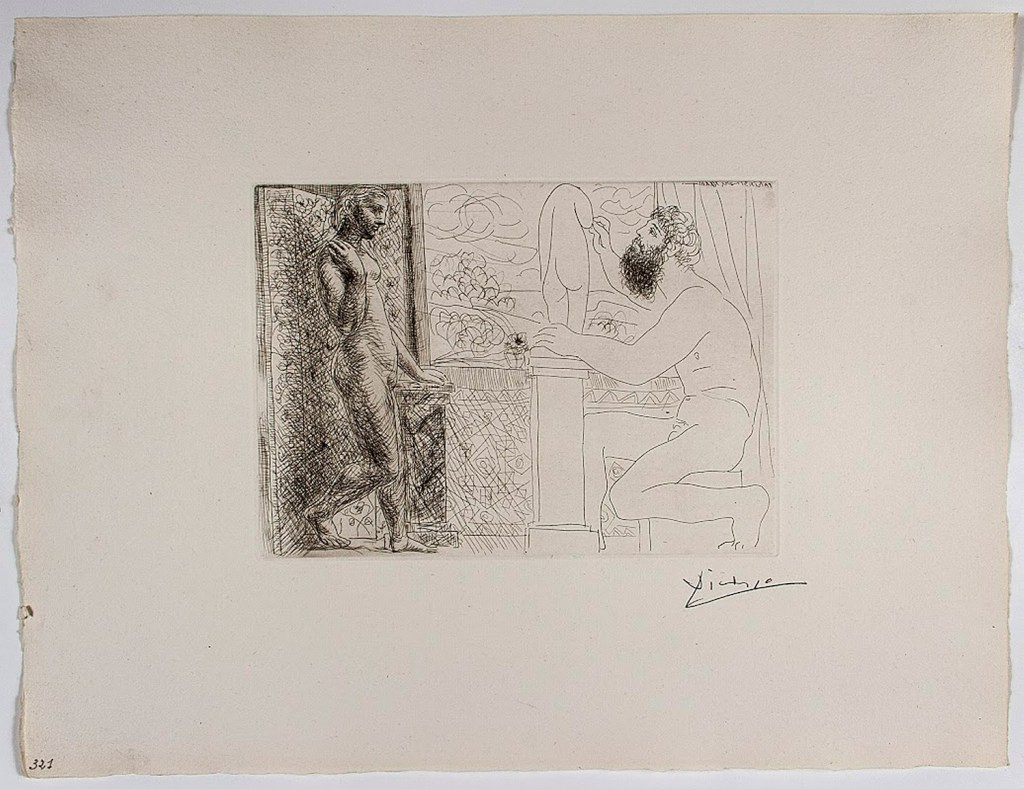

Critics and historians generally agree the suite as a whole represents Picasso’s masterpiece achievement in the print medium. With this work, Picasso explores themes that occupied him for years, including his own identity, creativity and sexuality, etched in a neoclassical style.

Colby’s set is rare because it’s never been shown publicly. About 300 sets were printed, but only 50 sets were printed on extra-large Montval laid paper. Of those 50, Picasso signed eight full sets.

Colby has one of them, the most recent gift of longtime Colby benefactors Peter and Paula Lunder, a wealthy Maine couple with deep ties to Waterville and Dexter Shoe Co. The prints are believed to be valued at about $4 million, although neither the Lunders nor Colby officials would discuss terms of the gift.

Before hanging the prints on the gallery wall, curator Justin McCann arranged a selection in a softly lit room on the museum’s lower level. A few were framed and hung on a wire wall rack. The others were laid flat, without glass or frames, the mats resting loosely on top of the prints. Picasso’s signature, lazy though it is at times, is clearly visible in each.

Colby’s set of prints has never been shown publicly, and their condition and provenance suggest relatively few people have seen them, let alone touched them.

The prints are pristine, without blemishes, tears or yellowing, and full of ferocity and feeling in quick, bold strokes. They suggest the rhythm of the artist’s life in France while he explored sculpture and carried on a long-term affair with his artistic muse, Marie-Therese Walter. Walter modeled for Picasso and was the subject of his sculpture and other forms of artistic expression.

Her presence is felt throughout the suite, expressed passionately by Picasso with his flowing, graceful and fluid lines. Many of the prints show the artist at work on a sculpture of the model, as she poses for him.

Themes that were present in the sculpture Picasso was making in the 30s, particularly mythology and sexuality, are present throughout the suite. McCann views the collection of prints as a record of Picasso’s thoughts, artistically and otherwise. The artist dated each etching, so it provides a visual diary of his life during an important moment of artistic development, McCann said.

These were turbulent times in the artist’s life, and the series reflects his turmoil. Some images, especially those from early in the series, are soft and reflective. Others are harsh and reactionary, perhaps reflecting Picasso’s anguish over the onset of the Spanish Civil War in 1936. Scholars believe the final prints in the series, populated by images of Minotaurs, reflect the violence of his country at the time.

Picasso made them at his home near Gisors, France, northwest of Paris, where he had studios for both sculpting and printmaking. He did most of the work in 1933 and 1934, and finished the suite in 1937, when he turned them over to his master printer, Richard Lacourière.

Vollard, who commissioned the series with the intent of selling them, died in 1939 before Lacouriere finished the job. A decade later, the dealer Henri Petiet bought the etchings, and museums began acquiring them beginning in the 1950s. The Colby museum’s set comes directly from the Petiet estate, said Director Sharon Corwin. That means the suite passed from Picasso to LaCouriere to Vollard to Petiet and then to Colby, via the Lunders. Colby’s set is the only completely signed deluxe set held by a college art museum and one of a handful currently held by a U.S. museum, she said.

McCann picked out the mat color and frames for the exhibition in the museum’s Davis Gallery. It is the job of Colby art preparator Stew Henderson to make the prints look good. He’s accustomed to working with valuable art and treats anything he touches as irreplaceable. “A Picasso, a Winslow Homer, a Whistler – everything is the same in my eyes,” he said.

But Henderson is also an artist, and the process of matting and framing delicate paper prints by one of the most famous artists in the world has been enlightening. Few people get to work with this art so directly and intimately. Henderson is less in awe than in admiration, he said.

“I look at these, and I see the different marks he is making and experimenting with different techniques. But the one thing I really admire, he just truly understands the figure. Even when he got cubist and tore the figure up, I look up some of these line drawings, and I see somebody who knows the body and knows the figure well,” Henderson said. “You are drawn to them immediately. There is something going on and you want to figure them out. They are astounding to see.”

After this show closes in August, Colby will rehang a selection of about 20 Vollard Suite prints in another gallery, for the benefit of students. That show will open Sept. 15. In 2018, the museum plans a major exhibition of the entire suite, with other work by Picasso and his contemporaries.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story