Why read a book about Johann Sebastian Bach? Isn’t the time better spent listening to his music instead?

Those are good questions to consider, especially before embarking on a book like John Eliott Gardiner’s 628-page “Bach: Music in the Castle of Heaven,” a deep and erudite dive into the music of someone who many consider the greatest composer of all time. And with the inaugural Portland Bach Festival coming in June, the questions are timely, too.

A book can provide context leading to a deeper understanding of a composer’s meaning and importance. For example, it’s one thing to listen to the Beatles and say they revolutionized music in the 1960s. A much richer perspective of their role in a post-war world becomes apparent when one learns that they developed their music chops by playing in Hamburg, Germany a mere 15 years after the end of World War II.

Gardiner, an acclaimed conductor, became a first-time author at age 69 when this book was published. He brings a conductor’s perspective to writing about Bach’s music, observing with practiced insight that, as a composer, “Bach appears to have stretched every imaginative muscle in his body to engage with his listeners.” For Gardiner, Bach was “like a chess grand master able to predict all the next conceivable moves” in a musical score.

Bach had a difficult childhood. Both of his parents had died by the time he was age 10, his family home was dismantled and he had to move in with a distant relative. As a young adult, he was disdained by those who held themselves out as the local intelligentsia because he lacked a university education.

Bach came from a family with six generations of musicians, and while that certainly provided momentum for his musical career, Gardiner writes that a commitment to hard work and craftsmanship, combined with a singleness of purpose, were keys to Bach’s success.

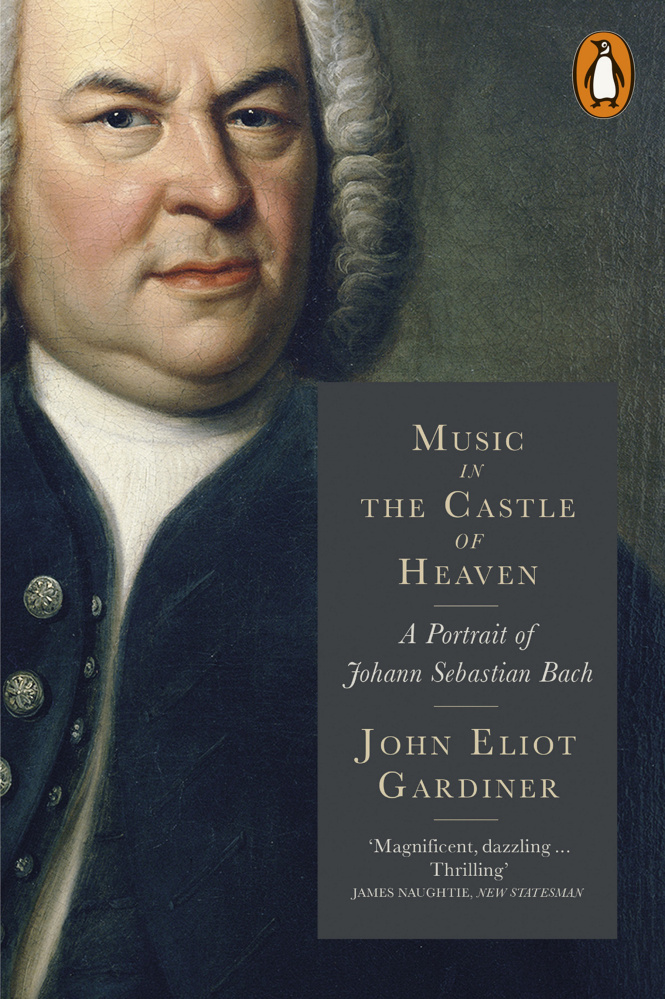

Gardiner methodically explains how Bach disrupted the musical establishment of his time and became “an unlikely rebel” who could be thought of as “genuinely radical or subversive” in the music world. Bach simply refused to be tied down by convention in any musical genre, a perspective that comes in stark contrast to the notion many people have of Bach from stodgy images of a “bewigged, jowly” old man, and of classical music as an art form that is resistant to change.

“Music in the Castle of Heaven” explores many dimensions of Bach’s life and music, but Gardiner says he does not mean it to be a comprehensive book about Bach. He writes that he focused only on the music he knows best, which Gardiner describes as music “linked with words”: Bach’s cantatas, masses, the St. John Passion and the St. Matthew Passion.

Gardiner’s discussion of Bach’s music is scholarly, energetic and at times passionate, but it feels incomplete. It lacks coverage of Bach’s monumental body of music that is not linked to words, including his sublime works for organ, cello and clavier and his chamber or orchestral music. (Fortunately, all types of Bach’s music will be performed during the Portland Bach Festival.)

Even today, Bach’s music “continues to affect people of all ages, religions and backgrounds.” Gardiner writes that it is a “beautiful and profound manifestation” of what humans are capable of and helps us access what is at the “emotional core of human existence.”

Dave Canarie is a Portland attorney and adjunct faculty member at the University of Southern Maine and Saint Joseph’s College.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story