Winky Lewis and Susan Conley didn’t stop time, but they came close.

Their new book, “Stop Here, This is the Place,” is a collaboration between friends and neighbors, between a photographer and a writer and between mothers whose children are best friends. At the beginning of each week for one year, starting in the spring, Lewis, the photographer, sent a photo to Conley, the writer, who responded by sending a small story back.

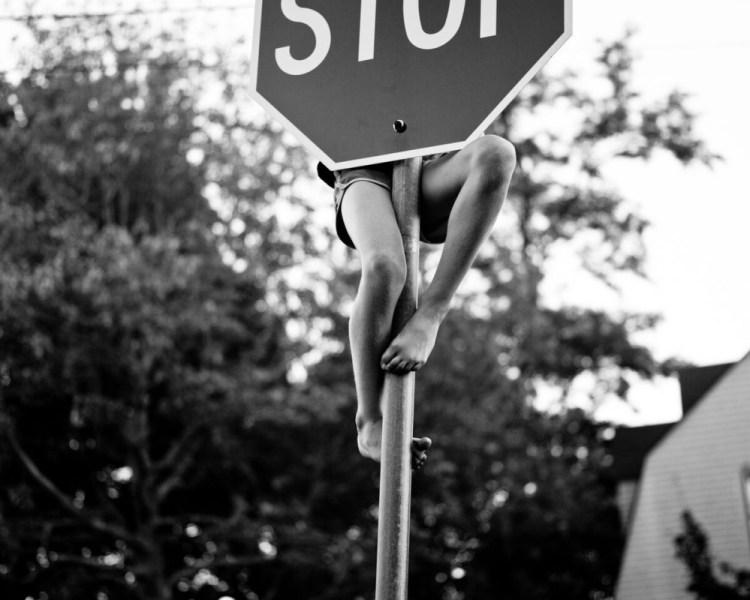

Most of the photos involved their kids and the wide West End street that serves as their playground. One house separates them. Their five kids – Lewis has three, Conley has two – are interchangeable parts. “We’ve raised our kids together,” said Lewis, who spoke about the book with Conley in a Portland coffee shop. Both families moved into the neighborhood on Bowdoin Street in Portland in 2001, at roughly the same time.

The photos and text tell a very small story about a very small place in a very big world. Motherhood doesn’t allow actual slowdowns, but the project enabled them to pause long enough to appreciate the small moments that often go unnoticed.

The photos and text tell a very small story about a very small place in a very big world. Motherhood doesn’t allow actual slowdowns, but the project enabled them to pause long enough to appreciate the small moments that often go unnoticed.

They’ll discuss their book Thursday night at the Portland Museum of Art. Portland illustrator Scott Nash will guide a discussion about their collaborative process, as artists and friends.

Their book, published by Down East, celebrates, as they say, “a year in motherland.” These are photos of children at play that capture moments of exploration and growth and friendship. They began the project in spring 2013, when the youngest of the child tribe was 9.

The book includes 52 photos and stories, one for each week.

From a writer’s perspective, the process was liberating and a bit terrifying, Conley said. On one hand, it was wildly fun, because she never knew week to week what the topic would be. The creative dialogue always began with the photo, which Conley treated as a blueprint or outline.

The challenge, she said, was finding her voice. Looking at the photos reminded her of growing up in rural Maine and allowed her to say things she’s always wanted to say about that. On one page, she writes with the authority of a mother:

“Right before the boy fell asleep, he asked his mother what he should dream about.

He was on his stomach with his little face towards the wall, leaving her already.

His dreams called to him, and the pale flowers rang like chimes.

Oceans, the mother said. And rivers. And trees.

That is how much I love you, she said.

More than these three things.”

On another page, Conley writes with the precocious imagination of a little girl:

“Flying. Yeah. It’s something I do whenever I can.

I fly in the morning when the sun rises.

I fly at night when there’s no moon.

I fly with my eyes opened or closed.

It’s the very greatest thing.

Sometimes I wear my new back-to-school outfit when I’m flying.

Sometimes I just put on my wings and practice lift off.”

The process allowed what she calls “the indulgence to go back in time.” She described her small stories as poetry, which was an early creative output for her writing. Writing poetry again – and writing about being a young child – felt like a gift “with a bow,” she said.

For Lewis, the photos allowed her to drop in on the lives of the children as an objective observer. Looking at the photos from the perspective of three years, she’s sometimes surprised at the range of emotions that are part of the year-long narrative. There are sprinkler fights and children dancing in the street, and there are pouty faces that underlie the trauma of being 12. “There are issues that are really real,” Lewis said.

The friends began their project in spring 2013. They barely talked about it, and neither edited the other’s work. They just reacted, as artists and mothers.

Lewis sent Conley a photo each week, and Conley wrote quickly. She often looked only briefly at the photo at first in search of her initial emotional reaction, and tried to write from that spot.

After a few months, they wondered if they were writing a book without realizing it. Lewis sent photos and text to her brother, a designer. Monty Lewis laid out of a draft of what a book might look like.

When Down East said yes, they realized their little world had suddenly become much bigger.

Initially, they wondered if it was a good idea to share the photos and stories of their children with strangers. Whatever fears they had were allayed by the reaction to the book.

Their kids like it, too – even the older boys who thought it was kind of dorky at first.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story