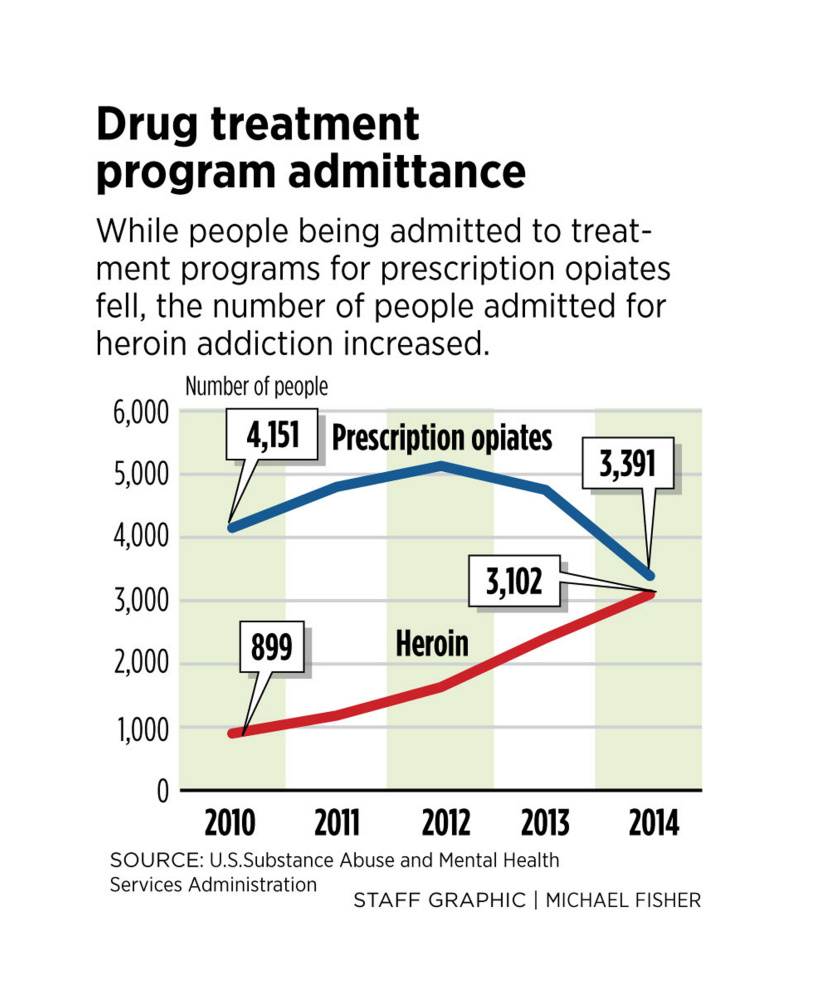

As the supply of opioid painkillers tightened and cheap heroin flooded into the state, the number of Mainers admitted to heroin addiction treatment programs nearly tripled over the last three years.

Prescription opioid treatment admissions in Maine had climbed steadily for more than 10 years before they declined in 2013, according to a review of federal data by the Maine Sunday Telegram.

The data suggest a correlation between increased heroin use and reduced access to prescription painkillers. In 2012, the state’s MaineCare system tightened its rules for patients receiving prescription opioids, reducing the number of prescriptions written for MaineCare patients. The Maine Department of Health and Human Services estimates that opioid prescriptions in the MaineCare system fell by 45 percent from 2012 to 2014.

The Legislature is now considering a bill that would further reduce the supply of prescription opioids.

Opioid prescriptions are a gateway to heroin, national studies show, as four out of five new heroin users were first addicted to prescription opioids, according to the American Society for Addiction Medicine.

While there’s no evidence that the 2012 MaineCare rules and the subsequent heroin crisis are directly related, many speculate that the MaineCare standards contributed to the heroin crisis by helping to reduce the supply of pills at the same time cheap heroin began flowing into Maine.

The number of patients in Maine-Care and other state-sponsored programs admitted to treatment for prescription opioid addiction declined from a peak of 5,132 in 2012 to 3,391 in 2014. Meanwhile, those admitted for heroin treatment, which had been relatively steady from 2001 through 2011 – about 1,000 to 1,200 per year – started spiking up, reaching 1,634 in 2012. By 2014, those being treated for heroin addiction in state programs nearly matched people being treated for prescription opioids, with 3,102 admitted to heroin treatment, according to the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, or SAMHSA. The numbers for 2015 are not yet available. About one-fifth of all Mainers are currently enrolled in MaineCare, which is what Maine calls its Medicaid program.

RESTRICTING OPIOIDS: ‘WE CAN’T NOT DO IT’

Sanford Police Chief Thomas Connolly, who has studied the heroin epidemic in Maine, said restricting opioid prescriptions is the right thing to do.

“We can’t not do it because we’re afraid of what might happen,” he said. “We can’t continue to have these drugs be overprescribed.”

But Connolly said there is a risk that if not done carefully, the new law could result in more people switching to heroin, which would be a strain on society, including the criminal justice system. Drug overdose deaths in Maine reached 272 in 2015, an all-time high, with most of the deaths attributed to heroin or prescription opioids.

Dr. Mark Publicker, a substance abuse physician and one of the leading addiction specialists in the state, said there’s not enough evidence to blame the MaineCare system for the heroin crisis.

Publicker said broadly speaking, the tighter supply of prescription opioids on the streets has a number of causes. These include doctors being less willing to prescribe opioids, pharmacies instituting better security measures, and drug manufacturers making pills with abuse-deterrent formulations. These factors, coupled with cheaper heroin flooding into Maine, have contributed to the epidemic.

One reason that heroin is so cheap is that fentanyl has been added to the mix in recent years, either on its own or combined with heroin. Fentanyl is an inexpensive opioid and has many of the same effects on the brain as heroin – and is much more potent.

When the supply of prescription pills was cut back, their street value skyrocketed, Publicker said.

“If you look at it from a capitalist standpoint, that’s what happened. It was a perfect storm,” Publicker said. “And heroin is a much better delivery system of the opioids to the brain. Once you switch from pills to needles, you don’t go back.”

Heroin met the demand for opiates, and it was far less expensive than pills bought on the street, he said.

“The truth is we just don’t know,” Gordon Smith, executive vice president of the Maine Medical Association, an advocacy group for physicians, said about the MaineCare rules and their relationship to the heroin epidemic. “It’s all anecdotal. But we do know it does have that potential.”

SAFEGUARDS FOR ‘LEGACY PATIENTS’

That’s why, Smith said, lawmakers, the LePage administration and the Maine Medical Association worked to revise a pending prescribing bill to safeguard patients currently taking opioids while at the same time further reducing the supply of prescription opioids.

The standards for prescribing opioids would apply to most doctors and patients in Maine and would be among the most restrictive in the nation, if approved. The Legislature’s Health and Human Services Committee voted 11-1 in favor of the bill last week.

Smith said the association is paying close attention to the so-called “legacy patients,” the 16,000 people who are on higher doses of prescription opioids, meaning they take more than 100 morphine milligram equivalents per day. Many of the higher-dose patients will soon be required to taper to lower doses if the bill passes.

Smith said the goal is to prevent unintended consequences – more people becoming addicted to heroin.

“We don’t want them running off and trying heroin,” Smith said. “The most vulnerable piece of this legislation is the legacy patients.”

Smith said by effectively targeting those patients, it could help alleviate the state’s heroin problem by successfully transitioning people to lower doses while at the same time preventing new people from becoming addicted to prescription opioids in the first place.

Health and Human Services Commissioner Mary Mayhew said there’s “no data” on how the MaineCare prescribing rules affected the demand for illegal drugs. But she said what is known is that the status quo is dangerous for patients who are on high dosages of painkilling drugs.

“The risk of overdose death is significantly higher when you’re on a higher dose of opioids,” Mayhew said.

Accidental overdoses are 11 times more likely for patients who are taking more than 100 morphine milligram equivalents, according to Dr. Noah Nesin, vice president at Penobscot Community Health Care in Bangor.

Dr. Christopher Pezzullo, Maine’s chief health officer, said the dosage maximum is important because the science does not support such high doses. The dosage cap of 100 morphine milligram equivalents proposed in the bill closely coincides with U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines on prescribing opioids that were released last week.

“Chronic pain is a complex diagnosis,” Pezzullo said. “But when you have doses higher than 100 morphine milligram equivalents, you’re not helping with pain. All you’re doing is increasing the side effects.”

Pezzullo pointed to recent research that shows over-the-counter pain medications are more effective than opioids at controlling pain.

Dr. Stephen Hull, director of Mercy Hospital’s Pain Center, is adamant that most people on prescription opioids, even on higher doses, can be tapered off and try new therapies to help them control pain. Those therapies can include physical therapy, massage, chiropractic and exercise.

Hull said research has shown that among certain patient populations taking opioids for pain, nearly 90 percent can be transitioned off the painkillers.

“We should make every effort to get them off of opioids,” Hull said. “This message is not getting out to some doctors.”

‘A PRISONER IN MY OWN HOUSE’

Audrey Foley, 66, of Westbrook said she was on oxycodone for nearly 20 years after hurting her back when she decided to give the Mercy Pain Center a try. At first she said she was reluctant to believe that she could quit the painkillers and not be in excruciating pain.

“Dr. Hull said, ‘Give me a chance,’ and after 11 weeks, I was off the painkillers,” said Foley, who at her peak was taking 240 morphine milligram equivalents per day. “I feel a lot better now.”

Foley said she has been completely off painkillers for three years, and her therapy consisted of physical therapy and exercise. She said she was often forgetful and in a daze while taking the opioids, but now is able to think much more clearly.

“I was mostly a prisoner in my own house, but now I can go out and do things,” said Foley, a retiree.

The prescribing standards in the pending bill – in addition to the dosage cap – would require that doctors use the Prescription Monitoring Program when prescribing opioids, mandate training before being permitted to prescribe opioids, and cap prescription length at 30 days for chronic pain and seven days for acute pain.

The new standards would allow for exceptions for end-of-life care, palliative care, cancer pain and potentially other diagnoses. Also, those currently on higher doses – the 16,000 taking more than 100 morphine milligram equivalents per days – would be given until July 2017 to taper to lower doses.

Publicker said the tighter prescribing standards are welcome, but he’s concerned that the state still lacks adequate treatment capacity, which means the opioid crisis will persist.

“Readily available treatment is simply not available in Maine,” Publicker said.

Those seeking treatment for illicit drugs but unable to access it in Maine number about 25,000 to 30,000, according to estimates from SAMHSA, the federal substance abuse treatment agency.

Mayhew said the state is expanding treatment options and studying the system to see if it could be operated more efficiently.

Correction: This story was amended at 10:40 a.m., March 30, 2016, to reflect a corrected version of a statement by Dr. Stephen Hull, director of Mercy Hospital’s Pain Center. He said research has shown that among certain patient populations taking opioids for pain, nearly 90 percent can be transitioned off the painkillers.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story