Testimony Tuesday in the federal trial of Gregory Owens ended with a scientist telling the jury that a hair found within the frame of a shattered door window in the house where Owens’ wife was shot couldn’t be tied to Owens.

Prosecutors, who are set to rest their case after four more witnesses Wednesday, have yet to present any conclusive physical evidence that Owens was at the house at 25 Hillview Ave. in Saco when a masked gunman broke in, shot Rachel Owens in bed in a guest room and then shot one of the homeowners, Steve Chabot, in the doorway of another bedroom.

The detail about the hair came out publicly for the first time while Michele Fleury, a forensic chemist from the Maine State Police Crime Lab in Augusta, testified during the seventh day of Owens’ trial in U.S. District Court in Portland.

Fleury also testified that two red stains found in the Chabots’ home tested positive for human blood, leaving jurors wondering about that crucial evidence until a DNA analyst testifies Wednesday about whether the blood could be matched to a certain person.

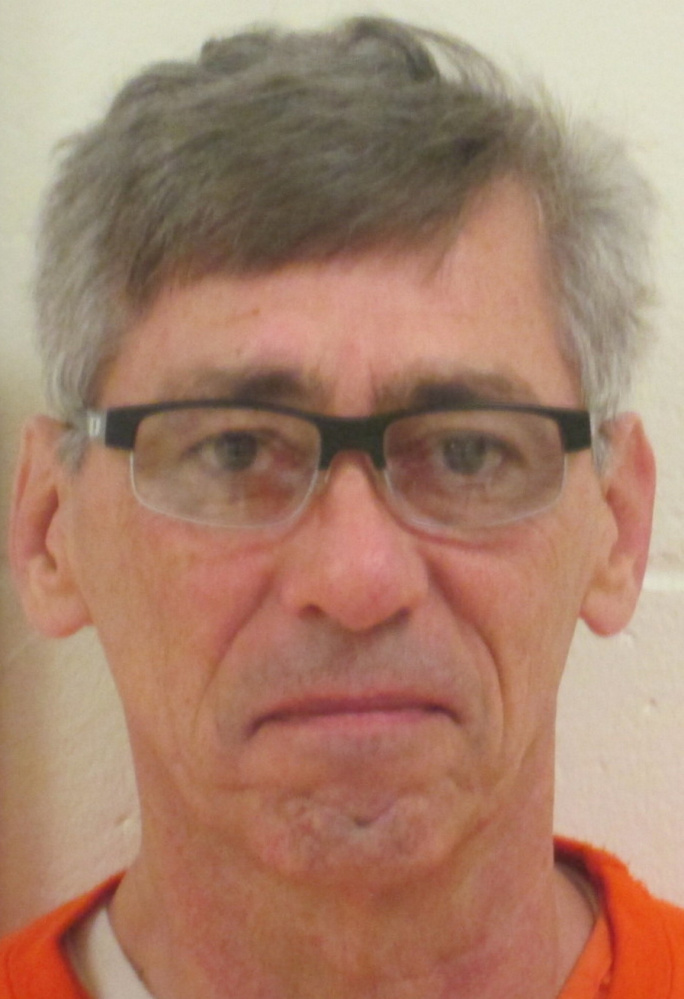

Owens, 59, is accused of driving from his home in Londonderry, New Hampshire, to Maine early on Dec. 18, 2014, and breaking into the Saco home of Steve and Carol Chabot, where his wife was visiting. Police say he wore a black ski mask over his face as he shot his wife and Chabot, while Chabot’s wife, Carol, hid in a third room.

Investigators say Owens shot his wife as his double life made up of lies began to crumble. His mistress from Wisconsin, Betsy Wandtke, testified Monday that she had discovered Owens had not left his wife years before, as he had told her, and had come to doubt his claims about being a military operative who went on frequent covert missions overseas.

Rachel Owens survived the shooting, though she still has a bullet lodged in her head and struggles to use her right arm. Steve Chabot also survived, and called 911 to report the shooting shortly after it happened.

Owens has pleaded not guilty to two federal counts: interstate domestic violence, punishable by up to 20 years in prison, and using a firearm during and in relation to a crime of violence, punishable by up to life in prison. After the federal trial, he will face state criminal charges, including aggravated attempted murder.

Prosecutors also called an Army officer from Fort Bragg in North Carolina to testify about Owens’ military record and refute Owens’ claims that he had special forces training.

“He was never assigned to work with any special forces units in the United States Army,” said Capt. Trina Thompson, who is in charge of sending reactivation orders to retired Army special forces veterans.

Thompson also said that Owens had never earned the Purple Heart medal, Bronze Star with Valor medal or Special Forces tab he wore in pictures.

Fleury’s testimony Tuesday set the stage for DNA evidence that will be presented Wednesday.

Fleury said she did scientific tests of blood evidence found in Owens’ vehicle when police pulled him over in Hudson, New Hampshire, about three hours after the shooting. Those tests confirmed that the reddish marks on Owens’ steering wheel and armrest were human blood. Owens told police that the blood was from him cutting his hand on a glass in his kitchen sink in New Hampshire, but investigators have implied that he cut his hand while breaking into the Chabots’ home.

Fleury also testified that two red marks in the Chabots’ home tested positive as human blood, one mark from downstairs by the basement door and another from a blood drop at the bedroom doorway upstairs, where Rachel Owens was shot.

Steve Chabot has already testified that the blood mark by the basement door was his from an unrelated carpentry accident that he didn’t fully clean.

The only mystery for the jury is who left the blood drop in the bedroom. That detail has not come out publicly, and court filings by lawyers leading up to the trial don’t say.

Fleury said the hair found in the broken window of the door into the Chabots’ garage had no root, which is the living cellular material used in most DNA tests.

“Without a root present, we can’t do nuclear DNA analysis,” Fluery said.

She said other scientists could have done mitochondrial DNA testing on the hair, but that was never done.

Mitochondrial DNA analysis is generally considered less accurate and more prone to mistakes.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story