SCARBOROUGH — It was 4 a.m. on Oct. 29, 2014, when Andy Cusack awoke to the sound of his cellphone ringing. On the other end was an old friend, Sean Caisse, and he sounded upset, Cusack later told police.

When they first met more than a decade ago, Caisse was a gawky teenager with dreams of NASCAR stardom. Cusack, the owner of Beech Ridge Motor Speedway and a kingmaker in the local racing community, became his mentor.

But by that chilly night in 2014, the two had not seen each other in more than a year, not since a bitter falling out, when Caisse went to the local police and made vague, sexually charged accusations against Cusack. The allegations never resulted in charges, but they drove a wedge between the two friends.

Shortly after the phone call, Cusack opened his front door to Caisse.

Six hours later, when police arrived, they found Cusack covered in his own blood from head to toe. He had a broken nose, cuts on his face, deep lacerations on one leg, several broken ribs and a punctured lung. His pinky finger was broken so badly that bone protruded from the skin. He told police he had been dragged around the house, duct-taped and tied to a chair and beaten all over his body. His silver Corvette was missing from his garage, along with a couple of thousand dollars in cash.

“Given the severity of his bad appearance, I was surprised to see Cusack conscious and alert,” Scarborough police Sgt. Steven Thibodeau wrote later in a report.

Still, Cusack gave a detailed statement and identified his attacker as Sean Caisse.

Less than 48 hours later, Caisse was arrested in Mooresville, North Carolina, and later extradited to Maine on charges of robbery, theft by unauthorized taking, and two counts each of aggravated assault and elevated aggravated assault. He faces 30 years in prison if convicted.

Despite the shocking nature of the crime and the swift work by detectives, the case was never disclosed to the media by Scarborough police, some of whom are close friends with Cusack and work security details at his track.

Neither Caisse nor Cusack would speak to a reporter about the incident or their relationship, and Scarborough police declined to discuss the case, saying it’s still under investigation. But a review of court documents, interviews with relatives and friends, and an examination of police investigative reports obtained by the Maine Sunday Telegram show how a talented, ambitious race driver came to lash out at a man who was one of his closest confidants and remains today among the community’s most prominent business owners.

“Andy and Sean were friends,” said Felicia Knight, a public relations professional hired by Cusack to handle questions about the attack. “Sean betrayed that trust in myriad ways, not the least of which was this criminal beating.”

Now, prosecutors and Caisse’s attorney appear to be girding for a trial, potentially dragging a convoluted, bizarre story into the public light.

“We intend to vigorously defend him against these charges and are confident that when the entire story is revealed he will be exonerated,” said Caisse’s attorney, Richard Berne.

* * *

Sean Caisse was 16 when he boarded a flight that would change his life.

It was 2002, and Caisse, his sister and parents were returning to New Hampshire from a vacation in Daytona, Florida, said Gisele Caisse, Sean’s mother. Caisse was seated next to a lean, clean-cut man with short hair. It was Andy Cusack.

The conversation shifted to racing, and Gisele Caisse listened as her son told about his career racing go-karts and hobby stock cars.

“It was really interesting, because for the first time I heard Sean tell (somebody) his life story,” Gisele said.

The arc of his career is a familiar one in the world of competitive motor sports. Caisse started at age 10 racing go-karts, first in Massachusetts and then in Pelham, New Hampshire, where he grew up. It was a father-son activity that took on a larger dimension.

Far from rinky-dink boardwalk amusements, the simple, low-slung karts reveal every glimmer of natural ability, and Caisse was a standout.

“It was pretty evident right from the start,” Gisele Caisse said. “It was something he had a real knack at. He began winning races.”

From 1996 to 1999, Caisse won seven karting track championships in four divisions, according to a driver biography published online.

Cusack was polite and friendly during the airplane conversation, but he did not let on that he, too, grew up around race cars, or that he was the owner of Maine’s most successful speedway, Gisele Caisse said.

Within a week, a card arrived in the mail from Cusack, thanking Caisse for the conversation and for sharing his snacks. Cusack revealed in the letter that he was the owner of Beech Ridge, and said he’d be watching out for Caisse. Later, he would even go to see him race in Lee, New Hampshire.

The Caisse family welcomed Cusack into their son’s life and knew that the friendship could help make the difference in their son’s racing career.

“He was a very highly respected NASCAR-affiliated track owner, and at that point we knew Sean had some strong talent,” Gisele Caisse said. “When you make a connection with anyone who is NASCAR-affiliated, you want to keep that connection because you never know who can help you move up to the next level.”

* * *

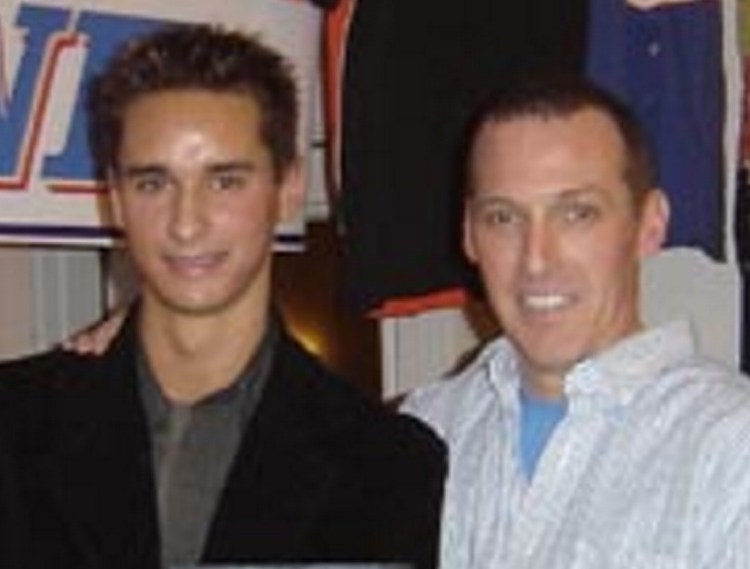

Sean Caisse celebrates his victory in the NASCAR Busch East auto race at Dover International Speedway in Dover, Del., in September 2007. Photogenic and well-spoken, Caisse was a natural in the racing world, his mother said.

Racing’s minor leagues are littered with drivers who have more talent than money, a product of the astronomical cost of fielding a successful race team. While some teams are self-funded, most rely on money from companies that use the cars as high-speed billboards for their brands, hoping a driver’s success at the track will transfer to positive exposure and sales.

With Cusack’s guidance, Caisse learned about the professional courtships, away from the thunderous spectacle on track, that make the sport possible.

Caisse, photogenic and well-spoken, was a natural, his mother said. He and his father made inroads with Casella Waste Systems, a sponsorship deal that allowed Caisse to compete professionally.

Cusack and Caisse traveled extensively together as Caisse’s career took off. Away from racing during the wintertime, Cusack, Caisse and others would take weekend trips to Cusack’s camp in Portage to snowmobile.

By 2005, Caisse landed a seat racing in the NASCAR K&N Pro Series East tour.

Andy Santerre, a respected Maine racer and fellow competitor that year, remembered Caisse as a fast and clean driver.

At a race at Dover International Speedway that year, Caisse was leading the field when Santerre worked his way forward, trailing the teenager.

“He knew I was going to pass him, and he put his hand out the window to wave me by,” Santerre said in an interview. “He was very respectful to us veterans.”

A year later, when Santerre started his own team based out of Mooresville, North Carolina, he hired Caisse to drive for him. Santerre and Caisse were successful, placing second in the series championship in 2006 and 2007, earning the team about $162,000 and about $80,700 in prize money, respectively.

All the while, Caisse and Cusack remained close friends. Santerre said that he paid Caisse a modest commission on his winnings, but Cusack also helped support the driver, buying him nice clothes, a car, a four-wheeler and a motorcycle, Santerre said.

At one point, because of the amount of money Cusack had lent Caisse over the years and the risk involved in the sport, Cusack took out an insurance policy on Caisse, according to investigatory records.

Caisse appeared to trust his mentor completely, granting Cusack power of attorney.

Around 2008, Caisse moved to Mooresville, North Carolina, one of NASCAR’s hotbeds of development. The career he dreamed of appeared to be within reach. He met a woman, Whitney Kay, and together they looked the part – he a handsome and talented race driver, she an aspiring model with blond hair, tan skin and a radiant smile.

But his timing was unfortunate.

Just as Caisse was looking to move up to a bigger, more competitive racing series, the world economy faltered. Sponsorship dollars, including his deal with Casella, evaporated.

“I really didn’t have anything going,” Caisse said in a June 2009 profile published in the Lowell Sun newspaper in Massachusetts. That year Caisse drove in only six races. At one point, he was down to his last $86, he said.

Steady seat-time was hard to come by. Between 2008 and 2010, Caisse drove in only 16 races, far from a full schedule. Prospects were slim.

His girlfriend got pregnant, and on March 8, 2010, the couple wed. Seven months later, Caisse’s daughter, Brielle, was born.

Over the next few years, it is not clear how he supported himself. At one point, Caisse briefly took a sales job selling racing equipment, a far cry from the podium finishes he was known for.

Life for the aspiring racer was about to become infinitely more complicated.

Sean Caisse spins out during a qualifying heat for the NASCAR Nationwide Ford 300 auto race in November 2010 in Homestead, Fla. Piece by piece, between 2010 and 2012, Caisse’s personal and professional life disintegrated. The Associated Press

* * *

Piece by piece, between 2010 and 2012, Caisse’s personal and professional life disintegrated.

The first to give way was his marriage. After 17 months and two days, the couple separated, and Kay filed for divorce a month later in October 2011.

Before the divorce was finalized, Caisse’s father, James A. Caisse, died unexpectedly in February 2012.

Caisse was shattered.

“His dad passed away at a very critical time in Sean’s life,” Gisele Caisse said. “He was going through a divorce. His racing career had pretty much come to an end.”

In divorce documents filed in North Carolina, Kay alleged that Caisse had been abusing painkillers, which he denied. Caisse ultimately relinquished custody of his daughter, and Kay went on to remarry another, more successful NASCAR driver, Brian Scott.

According to court records, Caisse returned to Maine in September 2013 for an unusual errand.

Caisse and another man went to the Scarborough Police Department intending to each file a criminal complaint against Cusack, a fact that is referenced in police reports about Cusack’s assault that were filed in court.

Scarborough police have declined to release the paperwork generated by Caisse’s complaint and would not discuss it, and a judge in Cusack’s assault case ordered the documents kept private.

But a lawyer involved in the assault case, Robert Andrews, agreed to describe the contents of the complaint.

Caisse initially told police that he was sexually assaulted by Cusack, but in an interview with an officer he did not describe any sexual contact, only strange habits by Cusack that seemed to have sexual undertones, Andrews said.

Caisse told police that Cusack sometimes walked around his house naked when Caisse was there, Andrews said. Caisse also reported that they spent time together in a hot tub, and when they traveled they sometimes slept in the same bed.

The report says the officer who took the complaint concluded at the end of the meeting that no crime had been committed, Andrews said.

Caisse was sent on his way, returning to North Carolina with his friend, who later fled back to New England because he claimed Caisse was “all messed up on prescription drugs,” according to a police report.

The accusations quickly made their way back to Cusack, who is close friends with multiple officers, and employs police at his track for security.

It’s not clear from public documents to what extent police interviewed Cusack or looked into Caisse’s complaint.

Police later learned that Caisse had approached a third man, asking if he would also make accusations against Cusack, but the man refused, according to police documents.

* * *

A faded sticker clings to the roll cage of a stock car before a race on NASCAR Nite at Beech Ridge Motor Speedway in Scarborough last summer. The speedway’s owner was the victim of a brutal attack at his home in 2014.

In the 13 months between Caisse’s complaint to Scarborough police and the alleged attack in October 2014, Caisse and Cusack exchanged several text messages. At first, Caisse threatened to go back to police with more accusations of sex abuse if Cusack did not pay him off, according to a summary of a police interview with Cusack obtained by the Maine Sunday Telegram.

Caisse intimated that he was suicidal and continued asking for money, offering to sell Cusack his dog for $2,500, Cusack told police.

As the spring turned to summer, Cusack’s distrust of Caisse began to soften, he later told police. They talked about meeting, to discuss the police report and their relationship, Cusack told police. He wired Caisse about $300, and on Oct. 28, 2014, for the first time in more than a year, Caisse and Cusack met in person, first at a train station in Wells and then at a restaurant. Cusack presented Caisse with a written contract for Caisse to sign, swearing that his 2013 complaint of sexual assault was false, according to a copy of the document obtained by the Maine Sunday Telegram.

“At the time of the complaints, I was experiencing emotional issues relating to the death of my father, loss of my daughter through divorce and loss of career,” according to the contract. “I made the statements regarding Andrew Cusack while I was in an unstable condition and experiencing financial hardships. … I confirm that my relationship with Andrew Cusack has been consensual in all respects. Our relationship has been one of mutual trust, respect and support. I attest that there has never been any unsolicited or inappropriate behavior or conduct between us.”

Cusack told police investigators that Caisse put his initials on the document but didn’t sign it, saying he needed time to think. They would continue talking in the morning.

But late that night, Cusack’s cellphone rang.

It was Sean Caisse, and he sounded upset.

* * *

What Cusack did not know was that Caisse wasn’t alone during his trip to Maine. Along for the confrontation was Caisse’s new girlfriend, Chelsey Delabruere, 24, of Mooresville.

Andrews, Delabruere’s attorney, said Delabruere was led to believe that Cusack owed Caisse money, and was holding a car for him. Caisse also told Delabruere that Cusack had sexually abused him – a story she believed.

Delabruere knew that Caisse had not come to Maine for a peaceful reconciliation with his old friend, Andrews said.

“She knew there was going to be trouble,” Andrews said. “She had no idea how significant Mr. Caisse’s actions were going to be.”

Following their initial meeting in Wells, Delabruere watched as Caisse became increasingly enraged, Andrews said.

Caisse hatched a plan.

Around 10 p.m. he texted Cusack to tell him that he was thrown out of his hotel room and that he planned to sleep in his truck at a rest stop, Cusack later told an investigator. Police would learn afterward that Caisse never checked into the room that Cusack had rented for him.

Several hours later, around 4 a.m., he called Cusack, telling him that a group of men had roughed him up and robbed him. Caisse was already parked outside Cusack’s home on Holmes Road in Scarborough. Could Cusack help him?

The track owner put on a robe and went to the front door. Soon after he stepped outside, the beating began, according to a police report obtained by the Maine Sunday Telegram.

“Sean, it’s me,” Cusack pleaded, according to the report. “It’s me, Andy, stop.”

Caisse did not stop, the report says. He sicced his German shepherd, Reece, on Cusack, opening up a wound on his calf. Caisse then grabbed Cusack by the genitals and dragged him into his house, blood spattering the wall of his entryway.

As Caisse initiated the beating, Delabruere stood off to the side, according to police reports. After Caisse dragged Cusack inside, she helped duct-tape his hands and feet to a chair, and she guarded him with a fire poker while Caisse rummaged through Cusack’s home.

They berated and cajoled him, trying to get him to confess to something. (In an interview with police later, Cusack said he felt as if he was being secretly recorded.)

All the while, the beatings continued intermittently, as Caisse’s mood fluctuated between calm and enraged.

Caisse forced Cusack to sign a check for $7,500, stole cash from Cusack’s safe, forced Cusack to sign a bill of sale for his silver Corvette, and made Cusack agree to send Caisse $7,500 each month for a year, the report says. If Cusack went to the police, Caisse threatened to have him killed, Cusack later told police.

Eventually, they agreed to untie Cusack, who was too injured to fight back.

At some point, Delabruere began to realize that Caisse was out of control, Andrews said. Cusack told police that once, when Caisse was out of the room, Delabruere apologized, saying she had heard so many good things about Cusack. She splinted his broken finger, cleaned up the scene and later made coffee, according to Andrews and police reports.

Before they left, Caisse even asked Cusack for a hug, or a handshake.

The couple sped out of town by about 11 a.m., returning to North Carolina with Cusack’s money and car, police allege. Their romantic relationship soured soon after, Andrews said. Caisse had isolated her from her family and friends, and his violence frightened her.

Delabrueure is charged with robbery, criminal restraint and theft by unauthorized taking. Andrews said Delabrueure is cooperating with authorities and plans to plead guilty.

Caisse was extradited to Maine in February, four months after the attack. He is living with relatives in Massachusetts while he awaits trial. After months of pretrial conferences, it is still unclear whether the matter will go to trial.

Caisse is due back in court Wednesday, when attorneys will again discuss with a judge behind closed doors whether Caisse will accept a plea agreement.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story