So many lovers of the wild have a theory about the right way to interact with it. With or without other people, with or without flashlights, at what speed, on or off the path. Thankfully, Jeffrey Thomson avoids this, choosing instead to dissect the relationship between humanity and the environment and leave it out before us, raw and gooey and difficult to look at. Instead of an answer, he creates a catalog of questions and never simplifies our layered relationship with place.

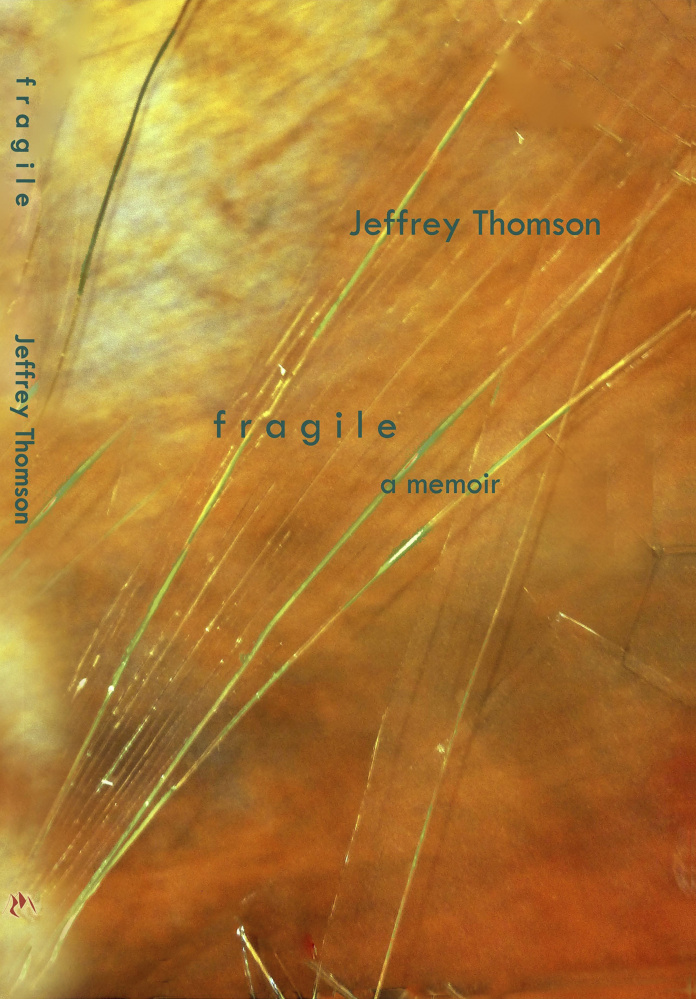

In his memoir, “fragile,” Thomson exposes his process to the reader, refusing to offer up a clean, considered, neat story. Perhaps this is his instinct as a teacher, to reveal the steps so that a student might learn from them. He includes excerpts of his journals and names the lineage of his thoughts (Plato, Edward Abbey, Charles Darwin, John Keats). He describes his struggle to lecture to his students during trips to Costa Rica, questioning both his ability to hold their attention and his ability to connect his thoughts in a way that satisfies him, let alone them. And he even offers a confession, choosing to come clean about the alchemy practiced by every creative non-fiction writer. “I put scenes separated by years and by thousands of miles – similar landscapes, sure, but similar is not same – I put them together because it suited the purpose of my story better.”

The story takes place over the course of years, across a series of landscapes, covering Costa Rica, Peru, Alaska, the American West, Italy and more. In the first section Thomson is a young man, mountain biking in Costa Rica, and in the last he is a husband and father, seeking the gravestones of his heroes in Rome. Currently, Thomson lives in Farmington, where he teaches creative writing at the University of Maine at Farmington. He continues to teach environmental writing courses using Costa Rica and its landscape as classroom and inspiration.

There’s a density to Thomson’s sentences, and his paragraphs could be explored like poems. It’s a style that fits the tropical landscape explored through most of the book, where we find some of the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet. And it builds the feeling of travel, where every detail becomes sharp, because everything is new and unknown.

Through writing, Thomson struggles to name what he sees and experiences and then to convey these things to his reader – who was not there. He describes the vulnerability of this process, how words themselves are imprecise instruments and how, as he writes, “The richness of the biological world overwhelms the limited human self.” But Thomson continues to try, marveling at the ability to use story and metaphor to reproduce something so limitless and complex. His goal is clear, “I am trying to gather two inseparable and divided kingdoms: the world and the word.”

Heidi Sistare is a writer and social worker who lives in Portland. She attended the Salt Institute for Documentary Studies and has work published in The Rumpus, Slice Magazine, and other publications. Contact her at:

heidi.sistare@gmail.com

Twitter: @heidisistare

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story