Editor’s note: This story has been rewritten to remove references to Bob Bailey, who had falsely described himself as a former Maine state trooper. A story describing that incident can be found here.

Andrew Kiezulas was given an oxycodone prescription when he injured his back slipping on the ice in 2007. The powerful drug eased the pain from his injury, but it also set him on a path to heroin addiction – a path that thousands of others in Maine also have taken.

It is the No. 1 reason heroin has become so prevalent in Maine, health experts say.

Kiezulas, who grew up in an upper-middle class neighborhood in Concord, Massachusetts but now lives in Portland, has a story that mirrors what specialists say is the typical way heroin addiction starts: People are prescribed pills legally for an injury, then later buy them illegally on the street. When prescription pills become too expensive, they turn to heroin.

Four out of five new heroin abusers become addicted through prescription opioids, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

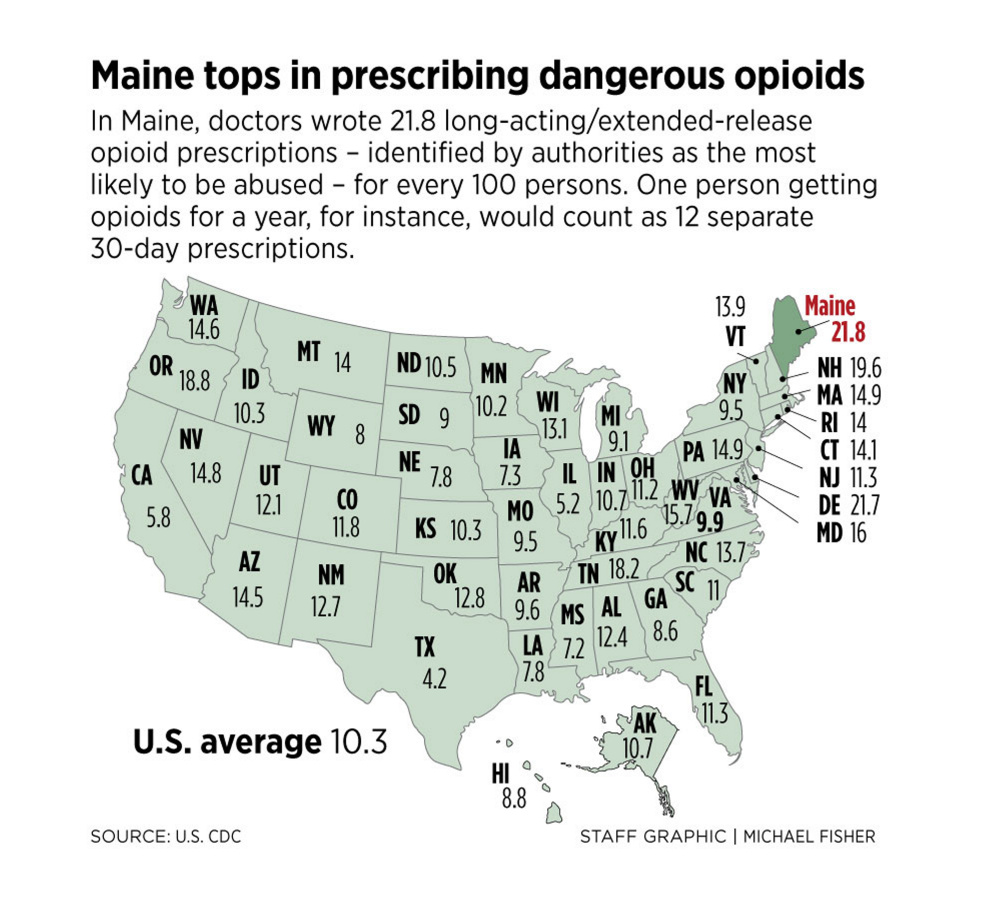

Despite growing awareness of the dangers of opioids, Maine has the highest rate in the nation of doctors prescribing long-term, extended-release opioids, according to a 2014 report by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The long-term opioids, prescribed for chronic pain, are the type of opiates most likely to be abused, according to the CDC.

Maine doctors are dispensing these long-term opioids at more than twice the national average, according to the most recent statistics available. Doctors in Maine wrote 21.8 long-acting/extended-release opioid prescriptions for every 100 persons, compared to the national average of 10.3 prescriptions.

While there are encouraging signs the tide is turning, especially in the MaineCare system, heroin deaths continue to increase.

These prescription pills have fueled Maine’s heroin crisis.

Experts say those taking prescription opioids are 40 times more likely to try heroin. By comparison, marijuana users are only three times more likely to try heroin than nonusers, the CDC says.

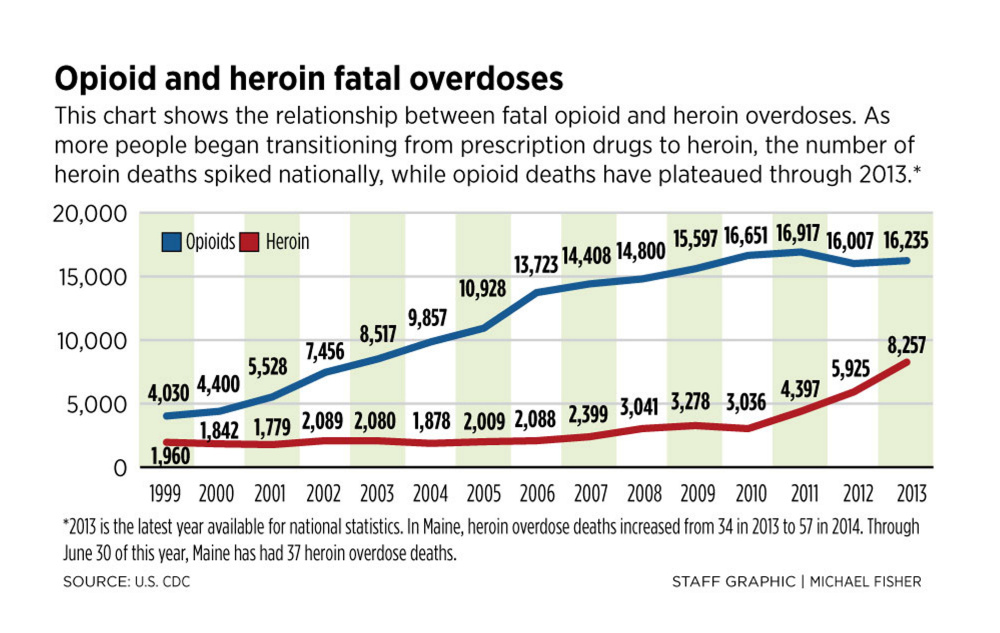

In Maine, a surge in new heroin users is overwhelming the public health system. The number of Mainers seeking drug treatment ballooned from 1,111 in 2012 to 3,455 in 2014, according to the Maine Office of Substance Abuse. Meanwhile, treatment centers have been closing. Heroin overdose deaths also have surged, going from 34 in 2013 to 57 in 2014, with 2015 on track to surpass last year.

Heroin abuse is entrapping people of all income levels and demographic groups, experts say, including upper-middle class and wealthy Mainers.

Public health advocates, addiction specialists, the medical community, the LePage administration and legislators say they are taking steps to stem the state’s heroin epidemic, although there’s some disagreement on how to do so. Gov. Paul LePage is emphasizing more law enforcement, while public health advocates call for more money to be spent on treatment.

One area where all parties seem to agree is the need to restrict opioid prescriptions, especially for long-term, chronic pain. MaineCare has tightened the rules for its doctors who prescribe opioids, and there are now far fewer such drugs prescribed for MaineCare patients compared to 2012.

But many problems persist. Doctors, especially those whose patients have private insurance, are still prescribing opioids at high rates, according to a leading pain expert in Maine. And with a reduced supply of opioids, the price of the illegal pills on the streets has gone up. People who were already addicted to prescription drugs find they can’t afford them and are now turning to heroin.

‘THEY MAKE THE PAIN WORSE’

After more than a decade of skyrocketing opioid prescriptions for pain relief – starting in the late 1990s – research in the past five years has indicated that in many cases, the drugs do more harm than good, said Dr. Stephen Hull of Mercy Hospital in Portland.

About 15 years ago, the medical consensus was that these new opioids flooding the market were safe and effective at treating pain, Hull said. Pain was considered the “Fifth Vital Sign” and these new pills would eradicate pain.

The consensus was wrong, Hull said, and research now convincingly proves it.

Hull, Mercy Hospital’s pain management director, said he’s “troubled” to see that Maine doctors treating privately insured patients are still prescribing opioids for long-term pain, even though the MaineCare system has successfully cut down the supply of opioids for its patients.

“They don’t work for long-term, chronic pain,” Hull said, flatly. “If they don’t work, why are we prescribing them? Not only do they not work, there’s compelling evidence that they make the pain worse.”

Hull referred to studies that showed that patients on long-term opioids reported worse pain than patients with similar diseases or conditions who were not taking opioids.

While MaineCare patients are now much less likely to be prescribed opioids – the number of opioid pills prescribed in the MaineCare system nosedived 45 percent in 2014 when compared to 2012 – the same is not true of patients with private insurance.

In the same time period, Maine patients with private insurers saw a 5 percent increase in opioid pills prescribed. The trend continues in 2015 for patients with private insurance. For the first six months of 2015, the latest figures available, private insurers had prescribed 24 million opioids, on track for 48 million opioids prescribed, compared to 44 million in 2014. By contrast, MaineCare prescribing rates for the first half of this year are flat compared to 2014, when 12 million opioids were prescribed to MaineCare patients.

“There’s a lag time in awareness,” said Hull, who helped develop the new MaineCare rules. “There are still doctors prescribing them.”

The lack of awareness is causing continued overdose deaths. Nationally, as prescription opioid abuse plateaued in the last few years, heroin deaths spiked while opioid deaths stayed about the same, according to the U.S. CDC.

Hull said the message has to get out to doctors who don’t see MaineCare patients that prescribing opioids for chronic pain is “not acceptable.”

Meanwhile, in the MaineCare system, doctors now have to jump through extra hoops to prescribe more than a 14-day opioid supply for their patients.

“If you want to prescribe more than 14 days, you have to justify it,” Hull said. “Anytime you can make the physician stop and think about what they are doing, that’s going to change behavior.”

Hull said once private insurance companies become more aware of the MaineCare rules, that should help insurers change their guidelines to match MaineCare’s 14-day rule.

John Martins, spokesman for the Maine CDC, said the state is working to increase awareness of the prescribing rules.

“We’ve begun reaching out to some of the top insurers and educating them about our achievements in the Medicaid program,” Martins said in a statement. “We’re also focused on ensuring participation in the Prescription Monitoring Program and encouraging all providers to submit and use the data.”

Maine does not force its doctors to use the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program, a tool that allows doctors to see what their colleagues are prescribing, and whether one of their own patients has a history of “doctor shopping.”

States that compel doctors to use the monitoring program, such as New York, Kentucky and Tennessee, have lower rates of opioid abuse, according to a 2015 article in Annual Reviews, a scholarly journal.

Each state runs its own program, and the rules vary.

In Maine, the MaineCare prescription program may be the key to further reducing opioid dependence, Hull said. It may not become apparent for years, as national statistics and state-by-state comparisons typically lag behind state-released numbers. For instance, the U.S. CDC study that shows Maine leads the nation in per-capita prescriptions for long-term, extended-release opioids was based on 2012 data, the first year the MaineCare prescribing reforms went into effect, but before they were in wide use.

Hull said he’s not sure a doctor mandate to use the monitoring program is necessary, but he believes as awareness grows, prescribing standards for opioids will change. The U.S. CDC is drafting new guidelines that will warn doctors to restrict opioid prescriptions.

“We should be getting people off of opioids as quickly as possible,” Hull said.

Hull said the research also shows that “chronic use of opioids has an adverse effect on our immune system.”

He said opioids activate the immune system cells in the central nervous system, which makes the nerves in the brain and spinal cord more sensitive – making pain worse.

That’s a problem because the immune system is one way the body naturally alleviates pain. It also explains why people on long-term opioids report more pain than those who aren’t, Hull said.

The opioids also cause brain functioning to be inhibited, causing a “foggy” or “hazy” effect, Hull said. People are more likely to suffer falls or get into accidents because their motor skills are inhibited by the opioids. And overall, they have worse-functioning brains.

“Our goal should not be to try to give people a pill that would make people pain-free, but to improve their functioning, their quality of life,” Hull said.

Hull said doctors should work on other solutions besides pills, such as physical therapy and exercise.

For instance, exercise is a natural way for the body to control pain because when we work out, the body’s immune system helps reduce inflammation.

THE ROAD TO ADDICTION

Kiezulas suffered his injury after finishing a sales call hawking fitness equipment in Reading, Massachusetts. He didn’t know it at the time, but the oxycodone he was prescribed to reduce pain would begin his five-year descent into heroin addiction.

Kiezulas nearly died from heroin by way of prescription drugs, in a suicide attempt.

Kiezulas had to fight his addiction with all of his family’s resources, and still had a difficult time quitting the habit. He might never have become addicted had it not been for his oxycodone prescription, although he previously had substance abuse problems with other drugs.

Kiezulas said he liked the feeling he got from oxycodone so much that he used up his 30-day prescription in less than a week, in 2007.

By 2008, Kiezulas had graduated to heroin because buying the prescription pills illegally cost too much. He attempted suicide in the fall of 2011, overdosing by injecting at least triple the amount of heroin into his bloodstream than he normally took.

“I didn’t see another way out,” said Kiezulas, 34, now a senior chemistry major at the University of Southern Maine. “I was so sick of taking the drugs, and yet I couldn’t imagine getting off of the drugs I was on.”

When he woke up, his skin was blue, but he was alive.

“I was upset that I was alive, and I was like, ‘What the hell do I do now?’ ”

Kiezulas, who grew up playing football and lacrosse and experimented with alcohol, marijuana and other drugs in high school, said he was not a hard-core user, but more of a “party drug” user.

That changed when he injured his back and ended up with two herniated and four bulged discs.

The addiction to opiates took hold almost immediately.

“Imagine something that calms you down, relieves your anxiety and gives you energy to do things. It kills your physical and emotional pain. It gives you a feeling of invincibility,” Kiezulas said.

The problem with heroin is that you have to keep using, Kiezulas said, or you experience severe withdrawal symptoms, including vomiting and migraine headaches.

Trying to get a heroin user to stop without help is a recipe for failure, he said.

“It was very, very difficult and I had an incredible amount of support and help,” he said.

After his suicide attempt, he sought help from his mother, who agreed to pay $6,000 out of pocket for a 30-day private treatment program in New Hampshire. Kiezulas was uninsured at the time.

Then his mother paid his $900-per-month rent to live in a communal “sober house” setting in Portland, where he lived for two years, starting in 2012. The rent paid for his shared room and a 12-step treatment program. His mother also paid his tuition to study chemistry at USM, a luxury many others recovering from heroin abuse won’t have.

“Putting my name and date at the top of the page and turning in homework has been a source of huge pride for me – just having that feeling of accomplishing something worthwhile,” he said.

Kiezulas said he’s giving back by joining the Maine chapter of Young People in Recovery and volunteering many hours a week to get the word out about the dangers of heroin use, and trying to help people who feel trapped in addiction.

Derek Willerson has the one bed of 14 reserved for uninsured patients at Milestone Foundation’s long-term treatment program in Old Orchard Beach. “I am pretty sure I would be dead or in prison if I didn’t get into this program,” the recovering heroin addict said.

FINDING RESOURCES

Kiezulas’ story shows that even for people with the financial means, quitting is difficult.

“We have an epidemic,” said Dr. Mark Publicker, an addiction specialist formerly with Mercy Recovery Center. “There is not a part of the state that hasn’t gotten hit by this.”

Kiezulas realizes he had far more resources than most heroin abusers, who often can’t get treatment and are stuck in a system that doesn’t help addicts quit.

Local fire departments say they are picking up overdose addicts, giving them the life-saving antidote Narcan and transporting them to the local hospital. Because treatment programs are scarce, in most cases addicts are released from the hospital within hours and are back at home or on the streets abusing heroin again.

Derek Willerson, uninsured and nearly homeless, was on the “hamster wheel” cycle of heroin abuse until he got lucky and secured a bed at Milestone Foundation’s long-term treatment program in Old Orchard Beach.

The program can last nine months or longer, and out of 14 beds, only one is reserved for uninsured patients like Willerson. The uninsured slot is funded by a grant, and the other beds are for MaineCare patients.

Willerson, 35, said he injured his hand on a rope swing after getting out of prison a few years ago for other drug crimes. He had never been addicted to heroin, though, but abused his opiate prescription immediately and then started using heroin.

“I am pretty sure I would be dead or in prison if I didn’t get into this program,” Willerson said. “There’s a reason I’m still on this planet. This is my opportunity to help fix these problems. I shouldn’t have had this many chances to live.”

Bob Fowler, Milestone’s executive director, said most uninsured people can’t get into 30-day programs. What’s worse, even those month-long stays aren’t enough time to help people fully kick their heroin addictions, and relapses are frequent.

Fowler said the system is failing, and he’s not seeing any proposed solutions that address the heart of the problem: the need for much better prevention and treatment.

SOLUTIONS CONTINUE TO ELUDE

The heroin crisis has become so acute that nearly every political and law enforcement leader is talking about what to do.

“There’s no simple solution, but there’s no doubt that these opiates are too prevalent,” U.S. Sen. Angus King told the Maine Sunday Telegram. “Jails across Maine have become de facto detox centers.”

Publicker, the addiction specialist, said Maine is in an especially precarious position because while more and more people are turning to heroin from prescription opiates, treatment is increasingly unavailable.

The Mercy Recovery Center, where he previously worked, served hundreds of patients and was one of the largest such programs in the state. The center closed this summer for financial reasons, as did Spectrum in Sanford. Maine Medical Center has started up a modest program, but it does not fill the gaps.

Publicker said the underlying reason is that fewer people have Maine-Care, and MaineCare reimbursements for substance abuse have plummeted, which means doctors are reluctant to take in more Maine-Care patients. For the uninsured – which many heroin users are – obtaining treatment is almost impossible.

“The entire addiction treatment infrastructure in the state is really in jeopardy,” Publicker said. “You could have a really enlightened attitude about addiction, but that doesn’t change the fact that treatment is unavailable.”

Even if fewer people become addicted to heroin through the prescription pipeline, those who are already addicted in most cases cannot kick their habits without treatment. So the number of addicts will keep growing unless treatment is expanded, Publicker said, even with reforms to limit prescriptions.

Publicker said he would like to be optimistic, but he thinks the future will be difficult.

Vern Malloch, Portland’s deputy police chief, said the police force now views users as victims, not criminals.

“In the past we would look at her as a perpetrator. Now we are more likely to look at her as a victim. She’s a victim of her addiction,” Malloch said.

Some police departments, such as those in Gloucester, Massachusetts, and Scarborough, are implementing programs to encourage heroin users to come to the police station on the promise of referrals to treatment programs.

The only drawback to such a program in Maine, Malloch said, is that there aren’t enough treatment programs in place to take them.

“We don’t feel like there’s resources to refer people to,” Malloch said.

Steve Coutreau, manager of the Portland Recovery Community Center, a support group for users, said he’s working with the Scarborough police to operate its program, which has had to refer people mainly to out-of-state programs.

STRETCHED TO THE BREAKING POINT

While LePage has emphasized an approach heavy on law enforcement, even threatening to call in the National Guard if the Legislature doesn’t fund more efforts to stem the supply of heroin coming into Maine, some are calling for a comprehensive approach that embraces treatment.

King said his staff is working on a Medicaid waiver that would allow uninsured people to obtain Medicaid-based recovery services. LePage, however, has refused to expand Medicaid in Maine and has tightened Medicaid eligibility requirements, kicking more childless adults out of the system. Addiction experts say it’s these young, uninsured, childless adults who are most vulnerable to heroin addiction.

“I would like to see if there’s a way to take a Medicaid-based approach,” King said. “Maybe there’s a way we can deal with this without a full-blown expansion of Medicaid.”

King said alleviating the heroin problem is one of his highest priorities.

Meanwhile, people are showing up at the Portland community center looking for treatment, which the center doesn’t offer. Coutreau said they may try to detox by themselves, which almost never works, and attend free support group sessions, which can be helpful but are designed as post-treatment support. Coutreau said the center is overwhelmed with people, up from 2,500 per month in the summer to about 3,300 in October.

“We are stretched to the breaking point,” Coutreau said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story