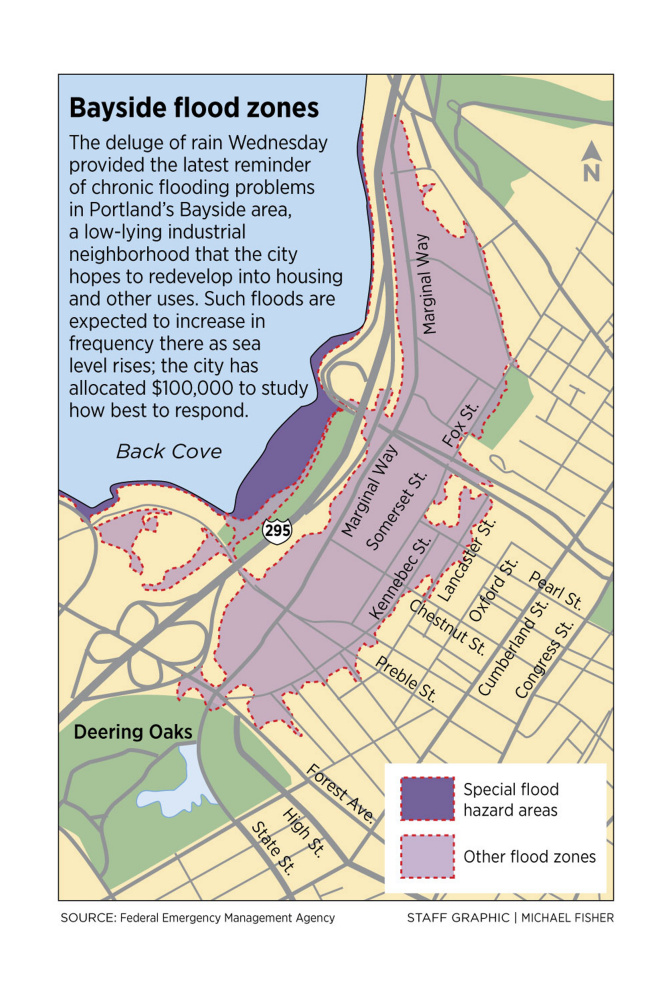

Portland’s Bayside neighborhood has been struck by significant floodwaters twice in 14 months, renewing debate about addressing the problem in an area prime for development that also is vulnerable to storms and sea level rise.

Numerous cars were stranded in several feet of floodwater Wednesday in the low-lying areas near the intersection of Franklin and Somerset streets after a storm dropped 5.6 inches of rain on Portland in a matter of hours. In terms of magnitude, the storm fell just shy of the deluge – the fifth-worst in Portland history – that dumped 6.4 inches on the city on Aug. 13, 2014, and also caused major flooding in Bayside and other city neighborhoods.

Flooding has been a problem for decades in Bayside and other areas of Portland, including near the Commercial Street piers.

But despite growing commercial development in Bayside in the area adjacent to Back Cove, the city has yet to take aggressive steps to address the flooding or adapt to the reality that water levels are rising in the Gulf of Maine. A major apartment complex planned for Bayside, known as the “midtown” project, would have raised the elevation of Somerset Street farther above sea level, but that project is in limbo amid disagreements between the developer and city officials.

City Councilor David Marshall said he has been frustrated by the “very slow pace” of work to address the flooding.

“We need a plan for how we are going to be able to handle this type of storm event because they seem to be happening more often, with some pretty severe consequences,” said Marshall, chairman of the City Council’s Transportation, Sustainability and Energy Committee. “I think that is going to be a challenge for (city manager) Jon Jennings to take on. It is going to take leadership.”

CITY TO PREPARE PLAN FOR ADAPTING

The potential effects of sea level rise have been on the agenda in Portland for years, as it has been in coastal communities elsewhere in Maine and in states on both coasts. Although Maine’s rocky shoreline means it may see fewer impacts than coastal states to the south, communities such as Saco, Damariscotta and York already have begun changing building requirements in flood zones or incorporating sea level rise into their comprehensive plans.

Sea levels rose 7.5 inches in Portland from 1912 to 2011, according to tide gauges in the city. The rate of increase over the past two decades is roughly double that of the previous period. And scientists believe oceans worldwide will continue to rise as glaciers melt because of climate change, although estimates vary on the extent of that rise and how rapidly it will occur.

Peter Slovinsky, a Maine Geological Survey marine geologist who has worked with Portland and other communities on how to prepare for rising sea levels, said the likelihood of major flooding incidents in Portland increase tenfold when sea levels rise by a foot.

Slovinsky said the first step in planning how to adapt to rising sea levels is understanding a city’s vulnerabilities. Over the past several years, Portland officials have worked with Slovinsky, as well as local university researchers and organizations such as the federal Department of Homeland Security and the Portland Society for Architecture, to begin to identify those vulnerabilities. The bigger challenge – financially and politically – is to identify the next steps in what will inevitably be a costly and years-long process involving changes to zoning and building codes, as well as extensive infrastructure upgrades.

“We are toward the beginning of that process,” said Bill Needelman, the city’s waterfront coordinator and the man leading the city’s efforts to adapt to rising sea levels.

The city’s current budget includes up to $100,000 – paid out of Tax Increment Financing revenues from new Bayside development, not citywide property taxes – to begin working on climate change adaptation in the neighborhood. Needelman expects work on an adaptation plan for Bayside to begin some time in the next year.

He said city staff will likely use Wednesday’s storm to hone decisions about whether to close streets before major weather events and continue to inform decisions about upgrading infrastructure.

“It is going to be an ongoing process of learning to live with water, but also adapting our infrastructure to better deal with the water,” he said.

WORKING AROUND BAYSIDE FLOODING

Much of the area in Bayside was actually part of Back Cove or tidal marshes that were filled with gravel or debris after the Great Fire of 1866. As a result, parts of Bayside frequently flood during astronomical high tides. Wednesday’s storm presented a challenge because the deluge of rain coincided with a high tide, meaning that rainwater pouring into the stormwater system had nowhere to go.

Brandon Lerman, whose family has operated E. Perry Iron and Metal on the corner of Pearl and Somerset streets for four generations, is accustomed to flooding during heavy rain events and astronomical high tides. But Wednesday’s flooding ranked among the worst he has seen, perhaps topped only by the Patriots Day storm of 2007. E. Perry Iron and Metal did not sustain damage, but Lerman said he saw many cars stranded in the floodwaters around his family’s business and the Whole Foods Market across the street.

“Yesterday was unique,” Lerman said. “We actually shut down early. We rarely close early because of weather.”

Lerman’s business is located just down the road from the site of the proposed midtown development that has been at the center of the debate over flooding adaptations for years.

The city owns 3.5 acres of former industrial land along Somerset Street, an especially low-lying road known locally as “Somerset Lagoon” because of its propensity to fill with water during heavy rain or extraordinarily high tides. Cattails grow on the city-owned land, which has been under contract for years to be developed into hundreds of residential apartments.

Because of the recurring floods and predictions of sea level rise, the developer’s plan calls for building the ground floor of new buildings about 2 feet above the current street level. The city and developer, Federated Cos., agreed to share the $4 million cost of raising a section of Somerset Street by about 2 feet.

However, the fate of the midtown project is now unclear. It has been long delayed by community opposition focusing on the scale of the project, and the developer and the city are now mired in a dispute over the terms of the land sale contract.

SURMOUNTING PROBLEM EXPENSIVE

On Thursday, neither city officials nor the developers would provide an update on the negotiations or status of the project.

Marshall, the Portland councilor, said the city “sort of backed into this policy discussion of raising Somerset Street” because insurance companies made clear that buildings had to be constructed farther above flood stage.

City Councilor Jon Hinck said Portland has only taken “baby steps” in addressing the challenges presented by rising sea levels. While Hinck can envision a day when Portland’s waterfront is dramatically reconfigured – with more elevated or floating structures – he said the city has an obvious interest in preserving the historic attributes of Commercial Street. Any major changes in Bayside or throughout the city will likely be expensive.

“The city of Portland has to do a hell of a lot more, and it is a struggle for me,” Hinck said. “To the extent that it requires city financial resources, I find that to be a challenge because I am trying to keep (taxes) from rising.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story