BIDDEFORD — As heroin abuse surges nationwide, a team of University of New England researchers is delving into the biology behind why opiates are so addictive in hopes of developing safer prescription painkillers.

Communities across Maine and the country are struggling to keep pace with a resurgence in heroin abuse that is at least partly attributable to the rise in patient prescriptions for high-powered opiates such as Oxycontin, some of which ended up on the illegal drug market. After tighter restrictions were put in place to stem the abuses, prescription opiates became harder to obtain and costlier to buy for those who were hooked on them, and heroin dealers moved in to offer a cheaper but more dangerous alternative.

The result has been a significant increase in heroin overdoses – including 14 during a recent 24-hour period in Portland – and growing pressure on an already overburdened drug treatment network in Maine.

The National Institutes of Health recently awarded a $4.5 million grant to researchers at UNE in Biddeford and the Southern Research Institute in Alabama to begin early development of potential drugs that have the same painkilling capacity as prescription opiates but not the addiction risks. UNE professor of pharmacology Edward Bilsky, a veteran researcher of opiates and chronic pain management, said the work is also a valuable teaching tool for his graduate and undergraduate students.

“I try to use current events to say, ‘The work you are doing has relevance,’ ” said Bilsky, UNE’s vice president for research and scholarship, and co-director of the university’s Center of Biomedical Research Excellence for the Study of Pain and Sensory Function.

The number of Mainers seeking treatment for heroin addiction more than tripled – rising from 1,115 to 3,463 individuals – between 2010 and 2014, and the number of heroin overdose deaths in the state climbed from seven in 2011 to 57 in 2014, according to the state.

Nationally, the number of people addicted to heroin has more than doubled in a decade, from 214,000 in 2002 to 517,000 in 2013, according to a study released this year by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Bilsky has spent years trying to better understand the basic biology of the body’s “receptors” for opioids and how it plays out in the body. Prescription opiates became popular with doctors and patients because they are so effective at reducing acute and chronic pain throughout the body while allowing the recipient to function in most situations. But Bilsky said that over-prescription of opiates, combined with patients’ misperception that the drugs were safe because they came from a doctor, contributed to the current opiate addiction problem.

A July 2014 paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association, or JAMA, found that “the face of heroin in the United States is changing dramatically” as more older, white Americans living in suburban or rural areas turn from prescription opiates to the street drug. Although Portland has received the most attention in Maine, heroin abuse appears to be on the rise throughout the state.

The research is part of UNE’s focus on understanding the biological basis for acute and chronic pain while examining the human face of pain. In his office and all along the hallway in his division’s suite of offices, Bilsky has hung paintings of neurons – the cells in the nervous system that conduct signals, from pain to pleasure, throughout the human body – as well as one work, called “Fire,” by artist Jennifer Shifflet that depicts her chronic pain as a spinal cord surrounded by flames.

“Every morning when I walk through this hallway and building, I remember that we are doing this for people,” Bilsky said.

To help explain the biology of addiction, Bilsky turns to a topic likely to resonate with almost everyone: food.

Humans can likely blame our ancient ancestors for the fact that a bag of potato chips or a caramel-filled chocolate bar is so irresistible when the stomach starts growling. Researchers believe that humans evolved to crave salt, fat and sugar because they are necessities of life that were often in shorter supply in food until more modern times.

Eating fatty, salty and sweet foods triggers the “reward” centers of the brain. As it turns out, the naturally occurring components in opium as well as other street drugs also hit those pleasure/reward targets in the brain, but at much higher levels.

And those sensations are difficult to forget, which is part of the reason for their addictiveness, Bilsky said.

Drawing another comparison likely to resonate with the average person, Bilsky said he can remember every detail of the first time he was stung by a bee even though the intense pain was relatively short-lived. Those feelings are seared into his memory, he said.

Unfortunately, the same thing can happen with heroin or other drugs that overload the sensory system.

“It is very difficult to forget that, even if you are in recovery,” Bilsky said.

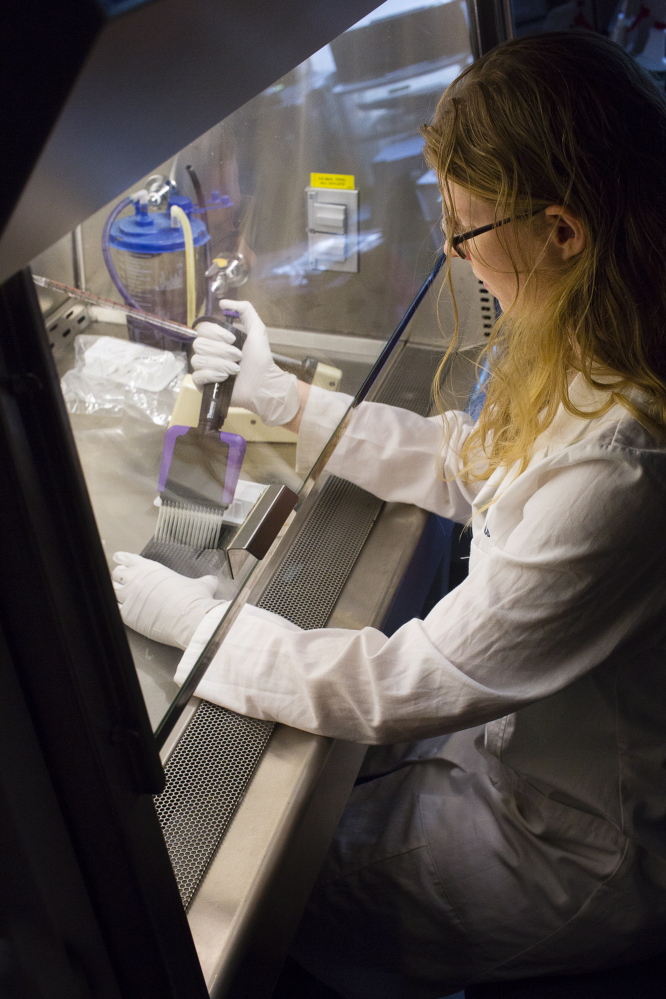

The NIH grant is supporting a group of three UNE researchers, two chemists at the Southern Research Institute and numerous laboratory technicians and students.

The research begins by testing potential chemical compounds in cell lines. Compounds that show promise are then tested in mice and rats, the latter of which have a similar taste for alcohol and drugs as humans. Only the most promising drugs could be developed for human clinical trials.

The goal, Bilsky said, is to develop a drug that can be taken orally, is stable in the body and can get to the brain to reduce pain but doesn’t have addictive qualities. UNE researchers also are hoping to develop compounds that could reduce the cravings of opiate addicts or lower the chance of a relapse.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story