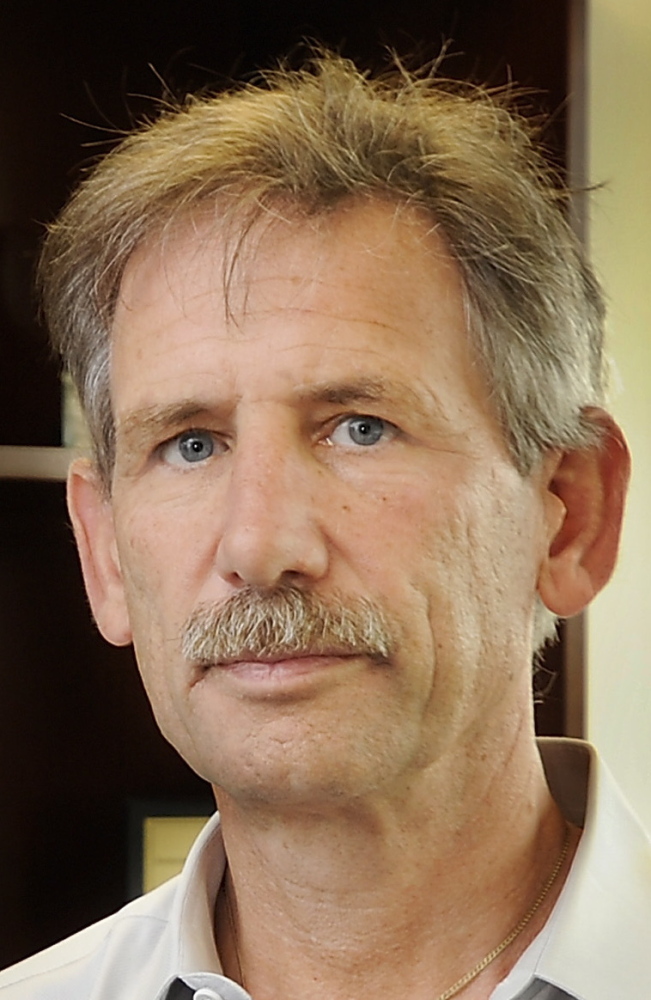

Bobby Monks Jr. smiles at the suggestion he’s a rabble-rouser.

The longtime Portland investor, developer and serial entrepreneur acknowledges he’s out to disrupt the investment world by pushing what some would say is a radical notion: The average American can hold Wall Street accountable, and in the process save a mint in brokers’ fees.

U.S. retirement assets totaled $24.2 trillion as of December 2014. That’s a lot of capital tied up in 401(k) plans, mutual funds and retirement accounts.

“Investors – that’s what you are if you have any of these investments – own the capital, and capital is power. Remember, these guys work for you,” said Monks.

His book, “Uninvested: How Wall Street Hijacks Your Money & How to Fight Back,” (Portfolio/Penguin, $25.95) encourages average Americans to stop sleepwalking through their investments.

“When we outsource our investing, we sacrifice control – but not responsibility,” he writes. “My goal in writing this book is to convince you that the best (and only) way to fix this broken system is to awaken a critical mass of engaged investors and recruit them to participate more fully in the investing process.”

The book doesn’t pull punches, calling out big banks and investment firms for intentionally complicating investments so they can reap more fees and fleece the average Joe. Monks offers a checklist of questions any investor should pose to money managers and a simple template to challenge them. (His website even offers to send questions on your behalf.)

Monks, a former board member of MaineToday Media, was in New York City on Monday, giving interviews to the Financial Times, Wall Street Journal and other media, hoping to drum up attention for the book.

While robust sales would be nice, he has a longer-term goal: generating interest in a new company he’s founding that embraces a different kind of investment model – collective investment partnerships. CIPs, as they’re called, draw heavily from mutual corporations, where customers are co-owners of the business and share in profits and governance (think credit unions, which plow profits into lower interest rates or rebates, and MEMIC, the workers’ compensation insurer that returns millions in savings to its policyholders every year.)

Monks knows high finance. In 2007, he co-founded Atlantic Bank and Trust and until recently was chairman and founder of Spinnaker Trust, which has $1 billion under management.

Monks recently spoke with the Portland Press Herald about the book and the plans for his new company, as yet unnamed. The following is an edited transcript.

Q: You’ve been involved in the investment world for a long time. What compelled you to write this book now?

A: I’ve circled the investment process for many years in a variety of businesses. From those experiences, I learned that the power of shareholders can make itself felt – that management has to pay attention. I also learned that the rules for money management need to change. They are not necessarily good for the average investor. And because I’ve been a serial entrepreneur who’s had many, many private equity firms invest in me, I’ve come to understand the importance of having the owner in the shop – having the investor right there. It forces everybody to confront problems quickly.

We want to wake up the latent power of investors, to make the investment process accessible to everybody, to show that the system isn’t so overwhelming. That complexity intimidates investors and therefore they’re willing to default to whatever fees they are subject to. What we’re saying is the average investor doesn’t necessarily have to do that. They need to engage with the person managing their money and ask the questions we’ve outlined in this book.

Q: Questions like, “Do you have any of your own money in these funds?”

A: Exactly. And “How do you get compensated? Do you get paid whether you make money for me or not? Do you have any conflicts over putting my interests first? How much are your fees?” Depending on how many layers you have, those fees can be huge.

Q: Such as?

A: 401(k)s are not all made the same. But in many, you pay an administrator’s fee. They hire a manager and there’s a fee attached to that. The manager puts it in a mutual fund and there’s a fee there. There’s a 60 percent turnover rate in the average mutual fund so there are a lot of trading costs. Those fees can add up. That can seriously affect your return in a bull market and cannibalize your return in a bear market.

For instance, a 1 percent management fee on a $25,000 investment with a 7 percent return over 35 years will cost you $65,000 in fees. Those numbers add up, especially for retirees.

Q: Who is the average investor? Is that your target for this book?

A: Middle-class investors. Anyone with a 401(k), or investments in a mutual fund or a retirement account.

Q: Your criticism of Wall Street and its players, as well as the regulators, is pretty harsh. Has there been reaction to advance copies of the book?

A: It’s important to note that not every money manager is a boogeyman. There are a lot of managers who do a very good job for their clients. But people have read it and have mixed opinions, as you can imagine. I assume there will be blowback from the industry – I’m quite critical of it.

I would add, though, that everybody recognizes there need to be changes.

Q: One of the more startling observations you make in the book is that the average mutual fund return was 40 percent lower than the stock market performance over the same period of time.

A: So you wonder, why doesn’t everybody just invest in index stock funds, or individual stocks? Of course, we’re seeing huge migration from the mutual fund market to index funds for just that reason.

Q: Tell me more about the collective investment partnership company you are trying to create.

A: The genesis for the CIP came from MEMIC, where I was on the board, and also a lot of the good things that came from Spinnaker. We borrowed the best organizational qualities and financial practices from an array of entities and mitigated the flaws that are so prevalent across the investment landscape. Making it a mutual corporation is key because I would rather see the average investor get that money than Goldman Sachs.

Also, I am an entrepreneur. The idea is to form this company and move forward with it. I might do it in conjunction with other companies. I might do it as an investment process with existing companies.

Q: Companies here in Maine or elsewhere?

A: It could be both. I love doing business in Maine.

Q: And the ultimate goal of the CIP?

A: Well, first this will take time. It’s a huge system. Regulators are completely overwhelmed and it’s a system subject to huge lobbying from the financial sector.

But one of the major factors of a CIP is to be able to get investors to say, “Here’s a company willing to share profits with me?” So you can ask existing money mangers, “Are you willing to share profits with me? Can I get a piece of the rock?”

I’m hoping for a contagion effect, so people will look at this and it will start blossoming out. People will start to think this is normal – that the average investor – the non-high-net-worth individual – will have access to a fair deal.

Business Editor Carol Coultas can be contacted at 791-6460 or at:

ccoultas@pressherald.com

Twitter: carolacoultas

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story