Dr. Robert Ecker dons a white surgical coat for his job at Maine Medical Center in Portland, but when he tells people what he does for a living – or explains to patients’ loved ones what he’s about to do – he goes blue collar.

“I do body plumbing,” Ecker says with a wry smile.

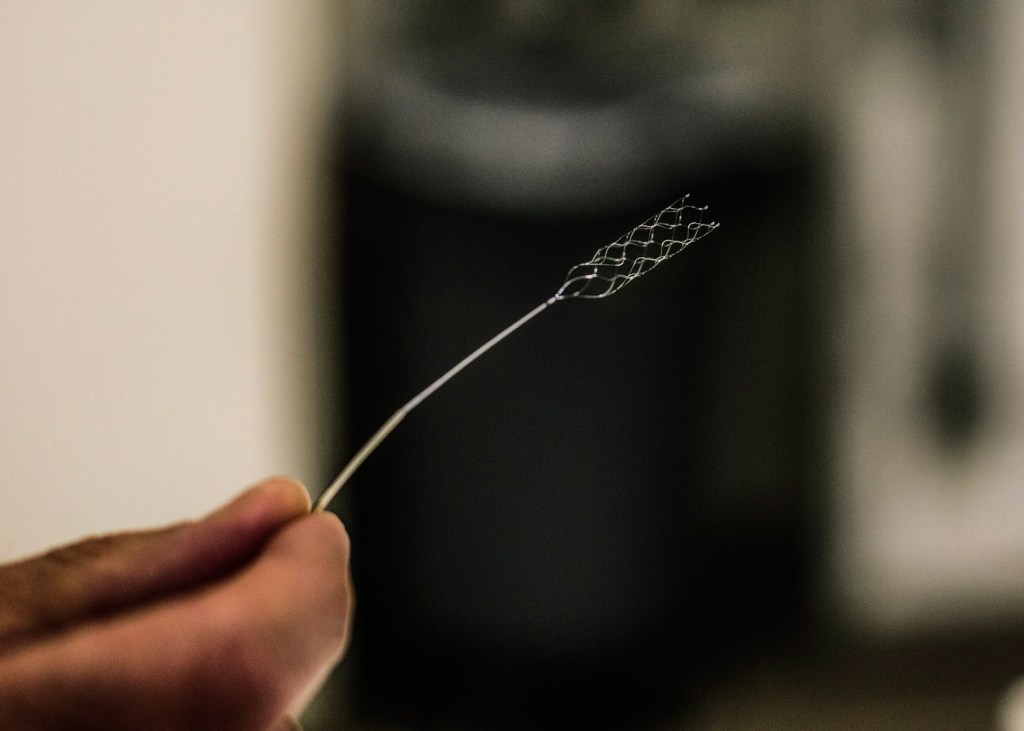

Ecker, a neurosurgeon who participated in groundbreaking national stroke research, holds a thin wire that turns into a tiny mesh at one end. It’s a surgical tool he has used hundreds of times in the past few years to save lives and prevent patients from suffering the debilitating effects of strokes – including paralysis and the loss of speech. Sixty percent can live independently within 90 days after the procedure, as long as the surgery is done within 4 1/2 hours after the onset of a stroke, which occurs when blood flow is cut off to a part of the brain.

The fifth-leading cause of death in the United States, strokes claim 130,000 lives a year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But four recent studies are offering new hope to stroke victims. One study – called Swift-Prime – in which Maine Med participated, was presented at the International Stroke Conference in Nashville, Tennessee, in February.

“This is a watershed moment in the management of acute stroke,” Dr. Lee Schwamm, director of acute stroke services at Massachusetts General Hospital, said in describing the new procedure at the conference.

While the procedure is only possible in about 10 percent of stroke victims, Ecker said the results are dramatic for those patients, and the results at Maine Med mirror the studies’ findings.

“We’ve doubled the number of people who are independent,” he said.

One of those is Bert Ricca, 38, of Windham, who had a stroke on April 15, 2014, after an undetected heart infection.

While he has difficulty talking and experiences right-side weakness, Ricca is living independently at home and continuing to improve.

“We thought he would be in long-term care the rest of his life. We were preparing for that,” said his wife, Danielle. Ricca ended up at Maine Med after he blacked out while driving in South Portland – he had enough wherewithal before becoming unconscious to pull off to the side of the road.

ADVANCEMENTS IN TOOLS

Police noticed Ricca’s disabled vehicle and he was rushed to Maine Med quickly after the stroke – a key factor in his favor. In surgery, Ecker worked the long skinny wire into Ricca’s brain and removed the clot – likely saving his life or preventing severe disability.

Ricca was one of four patients at Maine Med whose cases were part of the Swift-Prime study, which was conducted at 40 sites in the United States and other countries. The results were published this spring in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Ecker said the belief that the clot-busting tools would work has been around for over a decade, but research didn’t show promising results until the surgical tools improved to the point that practice could match the theory.

“It took a while for the tools to get good enough so that the results could show up in the research,” Ecker said.

Enter the retrievable stent, which Ecker and a team of Maine Med neurosurgeons have been using for about three years.

“We affectionately refer to this as a ‘stent on a stick,'” Ecker said. The tool – also called a “stentriever” – removes clots from the brain by traveling through the arteries to where the clot is located in the brain. Surgeons can introduce the stentriever through an arm or the groin area and guide it all the way to the brain.

The procedure is so new that most hospitals don’t do it yet – or don’t have the 24/7 capability that Maine Med does – and it’s not yet reimbursed by Medicare, Medicaid or most private insurance. Maine Med is the only hospital in Maine that does the procedure, Ecker said.

But the four international studies showed that the procedure dramatically improves outcomes in cases where it is applicable. Ecker believes the procedure soon will become more commonplace as awareness grows and insurance starts paying for it. It’s been a standard procedure at Maine Med for three years because of its strong results, he said.

The stent works by breaking up the clot and then removing it. Unlike a cardiac stent, nothing is left behind.

RAISING AWARENESS IS CRITICAL

The sooner a stroke patient can make it to the hospital, the better chance doctors have to limit the damage caused by a clot, Ecker said. If patients arrive at the hospital within three hours after having the stroke, and begin surgery within 4 1/2, their chances of recovery are greatly improved. Even if it’s several hours later, the surgery can sometimes be helpful, depending on how much damage has been done to a patient’s brain.

Ecker said awareness is key – both for potential patients and doctors in far-flung areas.

He said for the 10 percent or so of stroke patients who can be helped by the procedure, the difference between having the clot removed by the retrievable stent versus using only clot-busting drugs can be dramatic.

Ecker said a lack of awareness in Maine is reducing the number of people who could be helped by the procedure. While Ecker and his surgical team perform upward of 100 of the retrievable stent surgeries each year, he estimates 200 to 300 patients in the state could benefit from the technique. The research shows 60 percent can live independently after the surgery, but even the other 40 percent have improved outcomes.

Ecker said he has seen some dramatic recoveries – people who were debilitated by a stroke walking and talking because of the surgery.

“The personal satisfaction from seeing this is amazing,” said Ecker, 43, a native of Brookline, Massachusetts. “I could work the rest of my career and never come across anything as meaningful as this.”

For the Riccas, Ecker saved Bert from death or a lifetime of paralysis.

“When it happened, Dr. Ecker told me that he didn’t have time to fully explain what they were going to do, but that if it was his brother on the table, he would do the surgery,” said Danielle Ricca, a nurse. “I said, ‘OK, let’s go.'”

Bert Ricca did not have a quick recovery. He suffered a second stroke, was on 90 days of antibiotics to treat the heart infection and had numerous other complications. But he’s at home, able to take care of himself and the couple’s two children, ages 3 and 1, and goes to speech therapy while he continues to recuperate.

He often speaks in one-word sentences, but shakes his head vigorously “yes” when asked if he’s grateful for the surgery.

Their 3-year-old boy, Auger, helps dad with his words.

“It gets frustrating at times, but we’re very grateful that he’s here,” Danielle Ricca said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story