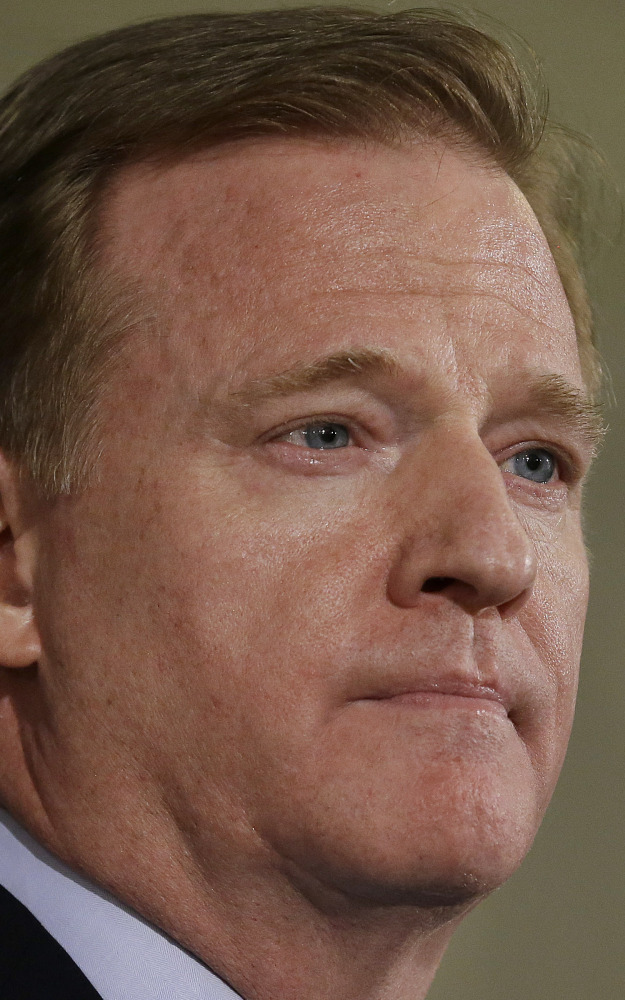

NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell predetermined guilt in Deflategate; that’s clear now. He has smeared Tom Brady and the New England Patriots without proper evidence or a competent investigation, and turned an unimportant misdemeanor into a damaging scandal as part of a personal power play to shore up his flagging authority. In other cases he just looked inept. In this one he looks devious.

This week at the NFL owners’ meetings, Goodell as much as admitted the Wells report is incomplete, despite the fact it took months, cost millions in legal fees and was supposed to be comprehensive. After all, the league used it to levy historically harsh penalties against Brady and the Patriots, claiming they deflated footballs in the AFC final. Nevertheless, Goodell opened the door to walking it back, saying he wants to talk personally to Brady, who appealed a four-game suspension.

“I look forward to hearing directly from Tom if there is new information or there is information that can be helpful to us in getting this right,” Goodell said.

Now this is the height of disingenuousness. Because we already know the Wells report missed crucial information and didn’t consider important facts. Wells either overlooked or ignored crucial text messages, used a firm with a reputation for bending science to fit predetermined conclusions, and cherry-picked the memory of an NFL referee. But that’s not all. The Wells Report left completely unexamined the fact the NFL has never considered the inflation of footballs to be a matter of great integrity or competitive advantage before now.

This is where Brady can blow the commissioner out of a courtroom and perhaps his job.

League history makes it obvious that Goodell is practicing selective enforcement for his own purpose. The NFL rules simply state footballs should be inflated within a range of 12.5 to 13.5 pounds per square inch. For more than a decade it has let each team provide a dozen of its own balls, and let quarterbacks choose them according to preference and feel, and to fiddle with the pressure without penalty. Aaron Rodgers has said he tells his equipment guys to over-inflate the ball.

That the league has never particularly enforced standards is evident in a hilarious section in which the Wells report eats its own tail. According to Wells, in a game between the Patriots and Jets it was discovered the refs inflated the balls to 16 psi. Brady got upset when he found them hard to handle. That’s how uneven ball inflation in the NFL is and how weak the Wells report is. The only firm evidence Brady ever had a conversation with anyone about ball pressure comes in this instance, when the ball was wildly over-inflated to 16 psi – by the league’s own refs.

What’s more, messing with the ball has been treated as a misdemeanor. In a very cold 2014 game between the Carolina Panthers and Minnesota Vikings, sideline cameras showed team attendants warming footballs in front of heaters, presumably at the behest of a quarterback. There was no scandal for “tampering.” There was not even an investigation. You know what kind of edict the NFL issued? A reminder. It sent a memo that softening the ball by warming it is not allowed.

At a minimum the Wells report is poor work and the NFL may well have skewed it. Just consider how the report used referee Walt Anderson’s recollections. It accepts Anderson’s account as accurate when it comes to how pressurized the Patriots’ footballs were in pregame. It also accepts Anderson’s account when he said there were two gauges available, one with a logo on it that gave higher readings by almost 0.4.

But when Anderson says he used the gauge that gave the higher psi measurements, the Wells report suddenly treats Anderson as inaccurate on this point – and no other. For no apparent reason, Wells insists Anderson must have used the other gauge that gave lower readings, and makes the Patriots look guilty.

As opposed to the higher gauge, which would put it in the realm of possibility that the footballs lost pressure by halftime due to the effects of cold weather and the Ideal Gas Law.

Once you’ve read this part of the Wells report, the words it so often employs – “more probable than not” and “likely” – begin to take on a pernicious tone.

The NFL created its own mischief. It wrote a rule that says each team can use a dozen of its own balls, and left it to the teams to inflate them without any regulation or consistent enforcement. Now, what a year ago was the subject of a mere memo has become the subject of a months-long million-dollar game of Gotcha. Why?

Don’t tell me it’s because Brady didn’t turn over his cell phone. Wells had all the phone records and texts between Brady and equipment manager John Jastremski, and there was no communication at all with locker room attendant Jim McNally. The records suggest Brady’s not withholding; he’s just a union man who objects to the precedent of giving his private phone to a commissioner who comes on like J. Edgar.

Here again, Goodell is practicing selective punishment. Brett Favre didn’t turn his cell over in a far more unpalatable case over sexual harassment in the workplace. Know what Goodell gave him? A $50,000 fine. With no suspension.

The commissioner needed a big case to restore his authority and prestige after a series of judicial embarrassments. Federal judge David Doty reversed him on Adrian Peterson’s suspension. Arbitrator Barbara Jones overturned him and found him not credible for suspending Ray Rice twice for the same offense. And former commissioner Paul Tagliabue issued a stunning rebuke in the New Orleans Saints Bounty Gate case, when he not only reversed player suspensions but found “arbitrary” as well as “selective, ad hoc or inconsistent” punishments by Goodell.

The guess here is Goodell’s support and respect among owners was eroded badly after he mishandled each case and turned them into months-long scandals that undermined public trust. Deflategate is nothing more than a bid to reconsolidate his power.

But it’s an overreach as usual, and whatever Goodell gained in the short term may be his undoing in the long term. There was an initial jolt of gratification that Goodell took the much-loathed Patriots and their owner down a peg. But after it will come a more rational examination of his conduct, and the flawed content of the report. And with that, distrust.

Sally Jenkins is a columnist for The Washington Post.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Modify your username

Please sign into your Press Herald account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe.