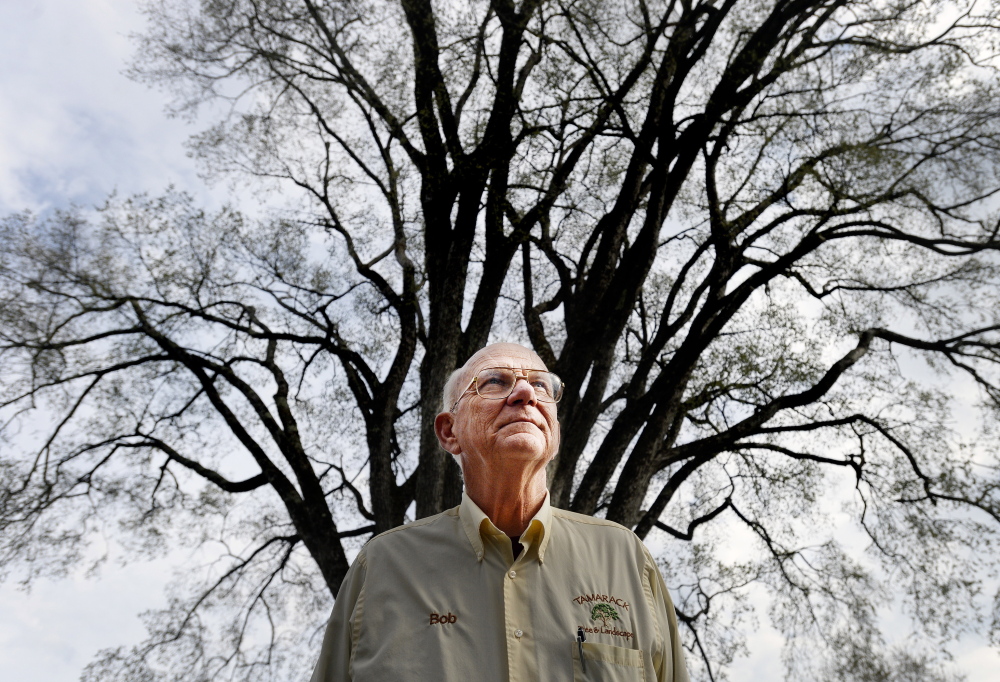

Arborist Bob Palmer of Tamarack Tree & Landscape Co. in Kennebunk will receive the Frank Knight Community Service Award on Monday as part of the state’s 2015 Maine Arbor Week celebration. Knight, you might remember, is the late Yarmouth tree warden known for his care of the famed elm tree Herbie, until it was felled in 2010.

We caught Palmer on the phone just as he was coming back from a tour of a prospective client’s property, where he was pleased to discover some rare American chestnut trees in the woods.

He was less excited to hear from us (“I avoid publicity as much as I can”), but since the celebration – and his award – help to promote Project Canopy, the urban forestry program, he agreed to talk. He’s a big believer in the joint program of the Maine Forest Service and GrowSmart Maine to assist municipalities with funding and support for planting and protection projects.

Our conversation ranged from how trees sucked him into the arborist business to why he thinks trees matter so much (and it’s not about absorbing carbon dioxide and producing oxygen).

ROOTS: Palmer grew up on farms in Falmouth and Cumberland. His parents had apple and pear orchards, grew flowers for the cut market and produce for farmers markets. They grew King apples, which Palmer said went out of fashion in the 1950s. His first summer job, at age 16, was working for a tree company. “A veteran (arborist) told me that it would get in my blood, and I would be a tree man forever,” Palmer said. “And I told him, ‘No, I am going to college and I’m not going to be a tree man.’ ” But the fortune teller was right; as soon as Palmer graduated, he went into the arborist business.

WHAT IS IN A NAME? He and partner Wayne Cutting started Tamarack Tree & Landscape Co. in 1976, working primarily in York County. Why Tamarack? “It is a native tree and we were looking for a name that once people could pronounce it, they would remember it. And it is a very pretty tree.”

NIGHTMARE ON ELM: Palmer started working with Kennebunkport to save its elms from Dutch elm disease in the late 1970s and has never stopped. When he started, the elm losses in town were at about 20 percent per year. Given that Kennebunkport in the 1950s had 2,000 elms, that was a massive lost. By 1983, the losses had dropped to 5 percent per year. “Since then I don’t think we have lost more than 1 to 2 percent a year,” he said. About 100 elms grow in Kennebunkport now, he said, the second most of any community in Maine (Castine has the most).

SALVATION ARMY: It takes a lot of volunteers and community involvement to save elms, not just one doctor making regular house calls. Palmer likens it to fighting cancer. “You treat it by recognizing it when it is a very small infection, you try to surgically remove it and you try to treat it chemically.” Likewise with elms: “If you are either skilled or lucky, you might succeed.”

Many majestic trees were lost to Dutch elm disease, which first rode into America in the 1920s on imported trees from Germany. But there was a plus side: “It led to a lot of money being dedicated to tree research that has benefited the care and understanding of how to work with trees,” Palmer said. “Rather than to just make trees look how we want them to look. Almost everything we do now has been modified in the last 40 years.”

TREE DREAMS: Is there a type of tree he’d like to see that he hasn’t? Like say, the spectacular African baobab? “I am at an age where I am dumping things out of my bucket list,” Palmer said. “I’d love to travel the world, but that is not going to happen.” But domestically, there might be a tree or two on his bucket list; while he’s seen the giant sequoia, he has yet to visit the coastal redwoods. With grandchildren in California, he might just get there soon.

TOP REASON TO CARE ABOUT TREES: “They are wonderful for the soul,” Palmer said. “They speak to our origins as no cellphone could ever do.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story