Tom Parks knew, the moment the two police officers knocked on the front door of his Saco home.

“You’re here about Molly,” he told them. It wasn’t a question, but a statement.

Yes, the officers told him. Your daughter has died.

At that time, they either didn’t know the cause or wouldn’t say, but her father knew.

Molly’s younger sister, Kasey, knew as well.

“I paced myself a long time ago for this day,” she said. “I knew it was gonna happen eventually. I prepared as much as I could but you can never prepare yourself fully for something like this.”

At 5:30 p.m. on Thursday, April 16, Molly Parks, who grew up in Old Orchard Beach, was found unconscious in the bathroom of the Manchester, New Hampshire, restaurant where she worked. A needle was still in her arm, a lethal dose of heroin in her blood. She was 24.

When it came time to write her obituary, her family could easily have glossed over how she died, like so many other obituaries of young people that use vague terms like “suddenly” or “unexpectedly,” leaving readers to make their own assumptions.

But Molly Parks’ obituary, published in the Portland Press Herald on April 20, was unusual because it left nothing to the imagination.

“Along Molly’s journey through life, she made a lot of bad decisions including experimenting with drugs,” the obituary read. “She fought her addiction to heroin for at least five years.”

Tom Parks said the family chose the brutally honest route for a reason.

“We didn’t want to hide it, because we thought that if we put her out there maybe, maybe somebody, someplace …” he said, struggling to articulate his point. “If it just made one person pause and say, ‘You know what, maybe I don’t want to do this anymore. I don’t want to be like Molly. I don’t want to die from this.’ ”

Tom Parks and his wife, Pat Noble, at their home in Saco. Parks’ daughter, Molly Parks, died of a heroin overdose on April 16, and the family, hoping to keep others from a similar death, decided to take the unusual step of publishing the cause in her obituary.

The frankness of Parks’ obituary has gotten national attention, mainly through social media, and highlights not only the growing number of deaths from heroin overdoses but the fact that the people who are abusing it – and dying from it – are not just the stereotypical street junkies.

In just three years the number of heroin overdose deaths in Maine has jumped from seven in 2011 to 34 in 2013, the most recent year data was available. That number was almost certainly even higher in 2014, according to anecdotal information from police.

Nationwide, 8,257 people died of heroin-related causes in 2013, up 39 percent from the year before, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Even the effects of heroin addiction can be devastating, with jobs lost, criminal behavior and sometimes irreversible damage to relationships. A study released recently by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration found that the number of people addicted to heroin nationwide grew from 214,000 in 2002 to 517,000 in 2013.

The alarming trend has a simple explanation: Prescription opiates such as OxyContin have gotten more expensive, less prevalent and harder to crush and snort or inject. That has driven addicts to heroin, which is cheap and abundant.

Gov. Paul LePage has said he wants to beef up enforcement efforts and increase arrests to fight Maine’s drug problem. Others say attacking the supply without investing resources into drug treatment simply doesn’t work.

But everyone agrees that too many people are dying.

Too many young people.

Too many like Molly Parks.

‘ONE THING MADE HER HAPPY’

She was born Amelia Alice Parks on March 13, 1991, but she was called Molly from the start.

Her parents divorced when she was 5 years old, and she split time between them.

Tom Parks said his oldest daughter was unique, someone who craved attention and love. She read and re-read all the Harry Potter books and favored classic black-and-white movies that most children born in the 1990s would never have heard of.

But Parks said he always worried about her.

“Addiction is in this family,” he said. “Both sides.”

Molly discovered alcohol in high school – not unusual – and was introduced to pills by a boyfriend, her family said.

“She started hanging out with the wrong crowd, the wrong people to be around for her mentality,” said Kasey Parks, who is three years younger than her sister. “She was never a leader. She was always a follower.”

From there, the jump to heroin was almost inevitable. Opiates produce the same sort of high and leave users with the same craving. Molly was 19 the first time she put a needle in her arm.

“When we’d talk, she would tell me things like she loves needles,” said Kasey. “She loved to watch herself shoot up. She told me it straight up. I cried my eyes out during that conversation but if that’s how she felt about it, I knew she was happy.”

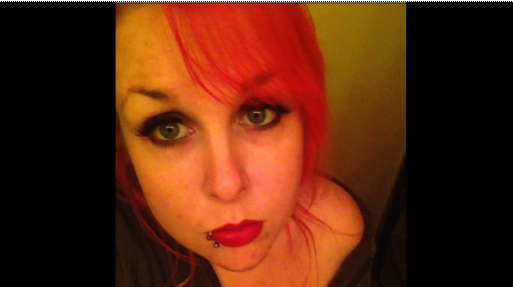

Kasey Parks says she talked to her sister, Molly Parks, about her heroin use. “She would tell me things like she loves needles,” Kasey said.

More people are using heroin now than at any point in the last decade, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration study.

In 2013, the most recent year available, 681,000 people used heroin, up from about 400,000 in 2007. Of that number, three out of every four said they were addicted – a sign of heroin’s powerful grip.

Experts agree that the sharp rise in heroin use is a consequence of the explosion in prescription drugs that peaked during the last decade.

Many addicts tell stories similar to that of Molly Parks. They started on prescription opiates – sometimes obtained legally – and got hooked. When pills became harder to get or more expensive, heroin was there to fill the void.

The federal study also found that although more people are seeking treatment for heroin addiction, many treatment centers already are at capacity.

In Maine, the number of people seeking treatment for heroin more than tripled from 1,115 in 2010 to 3,463 in 2014, according to the Maine Office of Substance Abuse’s treatment data system.

But that doesn’t mean they all kicked the habit.

Parks’ family tried to get her into treatment many times and said the process was not easy.

Last August, not long after Parks moved to Manchester to live with her aunt, she overdosed. She was unconscious when emergency workers arrived, but they used Narcan, a drug carried by emergency responders and some police that can reverse the effects of a heroin overdose, to save her.

She went to the hospital but was released within hours.

On another occasion, a treatment facility wouldn’t admit her because she was not displaying withdrawal symptoms.

Her family said she even once tried to quit cold turkey, a tactic that is difficult for heroin users because it often triggers violent, sustained sickness.

“We tried everything. That’s the whole thing. We tried to cajole. We tried being mad,” Tom Parks said. “You try everything. You try whatever you can to make them come away from the dark side.”

Kasey said she was close to her sister and since Molly’s death has been reading her journals to get a better sense of what led her to try to escape her life.

“She was honest with herself,” Kasey said, without revealing more. “She didn’t want this. But she couldn’t stop.”

Heroin, she said, was “the one thing that could make that girl happy.”

STARTING TO SPEAK OUT

Tom Parks grew up in Old Orchard Beach.

He knows times have changed since he was a young man, but he didn’t even realize heroin was available in the town that is best known as a summer tourist spot.

Old Orchard Beach could substitute for any community in Maine – the drugs are everywhere.

Roy McKinney, director of the Maine Drug Enforcement Agency, said his agents are arresting more traffickers than ever before, especially out-of-state traffickers, but they can’t eliminate the supply.

He commended families like the Parkses for being open about their loved ones’ addiction.

“I think families used to just move forward and sort of keep quiet about that person’s addiction,” he said. “Now they are starting to speak out and we’re starting to get a better sense of the impact, not just on families but on entire communities.”

On Wednesday, during visiting hours for Molly Parks at the Old Orchard Beach Funeral Home, hundreds of people came to pay their respects. Many were young. Many talked about the Parks family’s courage in stating the cause of death in her obituary.

Molly Parks isn’t the only young woman from Old Orchard Beach to die of a heroin overdose this year.

Sarah Beth Berlin, 25, was found dead on March 19 in her Old Orchard Beach apartment.

Old Orchard Beach Police Chief Dana Kelley said heroin has hit his town hard. Last year, emergency workers responded to 99 overdoses and administered Narcan 23 times.

“This is something we have tried to address with special enforcement details and we’ll continue to do so,” Kelley said. “We encourage people to speak out about what they might be seeing, but they need to be patient, too. We can’t knock on every door and arrest everyone on suspicion of dealing drugs.”

Complicating matters is the fact that addicts don’t have a typical profile.

Kasey Parks holds a memorabilia box full of photos of her sister, Molly Parks. “I paced myself a long time ago” for her death, Kasey said.

Both Parks and Berlin came from middle-class families that supported their children and tried to help them at every step.

“It’s not what people think,” said Pat Noble, Molly Parks’ stepmother. “People have a picture of what an addict looks like and what they don’t. It’s not. It could be anybody.”

“Not only could it be, it is your neighbor,” added Tom Parks. “You know what? You look out your back window and scan your neighborhood and you’re seeing one house for sure that somebody’s in there that has an addict in their family.”

Molly Parks’ family said they tried not to lose hope that she might free herself from the clutches of heroin.

“We saw her the Monday before she passed. And she looked so good,” her father said. “She was talking to us and she was happy. She didn’t give us any impression that anything was bothering her.”

Tom Parks said he feels the guilt that only a parent experiences.

“You know maybe there was one more thing, maybe something that I did when she was younger that I should have changed,” he said. “But all the coulda, woulda, shouldas in the world aren’t going to bring her back.

“She’s the one that had the needle. You had to convince her to stop. And that was impossible.”

The only thing the family can do now is share Molly’s story. They don’t want the problem swept under the rug. They don’t want it reduced to statistics. They don’t want her death to be in vain.

Since the obituary was published, the Parks family has been inundated with support, on Facebook and in letters.

It’s not enough to bring Molly back, but if even one person puts down the needle and goes into treatment, they say, it’s a start.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story