When Anthony D’Alfonso graduated from Westbrook High School in 2005, the baseball star was just days away from the big game, the Class A State Championship. The Blazes faced off with Oxford Hills in that bout – and came up short, 9-4 – but D’Alfonso had home runs still to hit and bases still to round before he would hang up his cleats for good.

He also had grades to improve, two colleges to play for, a soulmate to meet, a sweltering RV to squeeze into, a Mexican border to cross and cross (and cross some more), a professional contract to walk away from, a home to return to, friendships to rekindle, and a business to start.

Well, now he’s done all that, and settled into a life he loves. He works 40 hours as a warehouse manager for Agren Appliance in Auburn each week, and logs a couple dozen additional hours at his very own hitting school, Triple Crown Baseball and Softball Academy in Yarmouth.

“He was a little bit tough to tame,” says John Eisenhart, who was in his first year as head coach at Westbrook when D’Alfonso was a sophomore. “But that summer, I didn’t really give him an inch – I saw the potential in him, wanted him to be disciplined – and he responded to it.

“He didn’t like it all the time, but he responded to it.”

In his junior year D’Alfonso began to mature both as a leader and a player. “We put him in our lineup,” says Eisenhart. “I think, our second or third game, he had two hits and he never left our lineup after that.

“My brother Tim and I coached together; Tim was a positive influence in his life as well. Tim was a teacher at the time, so Anthony would call Tim every day in the summertime, and by the time I would get to our Legion games, Tim would be throwing batting practice to him.

“I would drive by the field and see Anthony’s mother throwing batting practice to him,” Eisenhart says, chuckling. “Anybody he could get to throw batting practice to him that summer, he would. He started to have some success, the work ethic kicked in.”

For Eisenhart, D’Alfonso was now the complete package: a 6-foot-4, left-handed swinger with a killer eye and the discipline to develop his talent. “Anthony went from being a total pain in my [butt], his sophomore year, to being a leader on the team and an All-State player.”

For his part, D’Alfonso credits Eisenhart and his other coaches for his, and the Blazes’, success in an exceptionally tough league. “Mainly, great coaches turned us into a great baseball team, because we were talented growing up.”

D’Alfonso’s adolescent recalcitrance returned to bite him after graduation. His grades weren’t strong enough to open many college doors, no matter how far he could blast a ball; he needed to improve them. He spent the next two years at Southern Maine Community College doing so – and playing for the Seawolves, of course (he’s in their Hall of Fame now) – before transferring to the University of Southern Maine.

It’s likely any number of D1 schools would’ve welcomed D’Alfonso onboard after his time at SMCC, with his academics much improved, but he wanted to be close to his family. So instead he joined the Huskies, where he won D3 All-American status for two consecutive years.

In 2009, three classes shy of graduation, however, an opportunity arose to join the pros.

His first stop was Traverse City, Mich., where he played independent ball in the Frontier League for the Beach Bums. Coming off a knee surgery, however, he didn’t light any fireworks. “I got 90 at-bats and didn’t hit so well. When the season ended, they didn’t ask me to come back.” He returned to Westbrook – call it home plate.

He wasn’t off the pro radar, however; not yet. The following year, he received an invite from a man named Francisco Ochoa to try out in Arizona for the Yuma Scorpions, an affiliate of the Golden Baseball League. D’Alfonso snatched up the prospect.

In Yuma, he found himself waiting, and waiting, and waiting. “I was sitting in my hotel room for two or three days, like ‘What is going to happen? Is this going to pan out?’ Here I am, ready to have my mom book me a ticket home, when this guy calls out of nowhere, and he’s like, ‘All right, the general manager is ready to see you hit.’” D’Alfonso nailed the tryout, knocking 13 of 16 pitches out of the park.

Naturally the Scorpions signed him on the spot. He performed well in his stint with them, hitting around .300, but Golden Glove Baseball, the equipment company that owned the squad, soon went belly-up. Ten or 15 games with no pay forced D’Alfonso to reassess his situation.

“I didn’t intend to get rich on it,” he says. “But I didn’t intend to make my parents go broke while I lived out my dream.” Disappointed, and increasingly disenchanted with the pros, he returned to Westbrook once more.

That’s when he met Angela Vanier, now his girlfriend of more than four years. Vanier also graduated from Westbrook, but in 2001, four years earlier than D’Alfonso; the pair hadn’t known one another as Blazes. But they had mutual friends, and became acquainted one night on the town.

At the beginning of 2011, Ochoa – who never seemed to have an official role in the organizations he associated with, but “had connections everywhere,” as D’Alfonso puts it – contacted D’Alfonso again. Again Ochoa invited D’Alfonso to Yuma to try out, this time for a Mexican team, the San Luis Algodoneros; D’Alfonso reluctantly accepted.

D’Alfonso took batting practice for Ochoa’s Mexican contact at a field within eyeshot of the border, until Ochoa asked him to cross into Mexico and do it all again. D’Alfonso consented, but also worried he was out of his depth. “I’m thinking, ‘Oh, man, I’m not cut out for Mexico; I’m really not.’”

Misgivings in tow, he left Vanier and his mother, both visiting, on the American side of the border, then accompanied Ochoa a mile into foreign territory. The two could barely communicate, as D’Alfonso spoke no Spanish and Ochoa little English.

When they arrived at the field, D’Alfonso – whose hands were already raw from earlier hitting three buckets of balls – found the entire team lined up to spectate. League rules restricted the number of foreigners on a team to five, so he needed to win widespread approval.

He did exactly that, and suited up for the team’s evening matchup – as well as their next 42, roughly half a season. He hit over .400 in that time, but couldn’t win the batting title, allegedly because he hadn’t played enough games. He was a diamond in the rough; the team as a whole hardly excelled.

“You don’t even sign a contract,” he says of the fly-by-night experience. “It’s so crooked. If you don’t [play well] for two weeks, you might be out of a team.”

Nevertheless, he says, “I had an absolute blast. People took me in like one of their own.”

For the first year of his Mexican career, D’Alfonso lived in Yuma, in his mother’s RV. Vanier quit her high-paying gig at Morgan Stanley in Portland, packed up her BMW and moved to Arizona to join him. “We parked it in an RV park, we drove across the border almost every game,” he says.

But of course, an RV in the desert in high summer was no Eden. The walls closed in and the air sizzled. “Living in an RV set in really quickly,” Vanier says. “We sat there and boiled in that RV for two months. It was 110 degrees every day. We just about killed each other.”

Vanier was outside her comfort zone in more ways than one. She’d grown up accustomed to structure and stability, and the D’Alfonsos’ willingness to take huge risks unnerved and irked her. She started a blog, The Bitching Mound, to chronicle her boyfriend’s trials, and her own.

“I was raised to know what’s happening on a day-to-day basis,” she says. “Him and his mom were both fly-by-the-seat-of-their-pants. I was like, ‘You guys are crazy!’”

Neither D’Alfonso nor Vanier could find a job between the 2011 and 2012 seasons; so they left the RV behind, packed up her bimmer and trekked back to Westbrook.

Then, for the 2012 season, the Yuma team rose from the dead. They offered D’Alfonso another contract – only to again yank the rug from beneath him. “They called me two weeks before the season and said ‘Everyone’s a free agent. We can’t get the money to fund the team.’”

So he dialed up Ochoa. The Algodoneros were happy to see D’Alfonso return. “I’d hit so well there, they removed a foreigner and gave me a spot right away. They booted a guy who later became one of my close friends in Yuma – but that’s another story.”

D’Alfonso played another half-season in Mexico, batting around .390. The team made the playoffs, but bounced in the early going. Management asked D’Alfonso at the end of the year to return for a full season in 2013, and he committed. He played all 80 games with them that year, and the team won their league championship.

It was during this time that Vanier found it in herself to relax her need for stability, perhaps because the couple found a small measure of it – just enough to clear her emotions and help her find a fresh balance. She took a new job in Tucson, and they rented a house.

“I just said, ‘I’m going to stop fighting it; he’s getting paid to do what he loves,’” Vanier says. “It took me a little time to accept that I’d probably take the same path. And he’s good, he’s so good.”

Whatever its cause, the shift in her mind also relieved a certain degree of D’Alfonso’s concerns; he wanted her to be happy. His sharpened focus paid dividends on the field. In 2014, he again played a full season with the Algodoneros, and the team won their second straight championship.

To top it all off, D’Alfonso led the league in batting average, homeruns and RBIs – the so-called Triple Crown, the most prestigious offensive award in baseball. Actually, he led the league in every single statistic except triples.

For reference, the league the Algodoneros play in is roughly the equivalent of an American AA league. In the U.S., the Algodoneros would match up on the field against the Sea Dogs. The Mexican big leagues, where D’Alfonso obviously appeared headed, is on par with the American AAA leagues.

“I had multiple calls to go play in the Mexican big leagues this year,” D’Alfonso says. And in fact, he joined a team, practiced and played several preseason games with them. But they were located deeper into Mexico, in Guadalajara, and the prospect of parting from Vanier for extended stretches caused D’Alfonso to review his circumstances again.

“It was kind of like a light bulb went on,” he says. “She was tired of her job in Tucson, I was working a job – not a career. It was a lot less worth it. Here’s someone who stuck it out by my side for the whole thing. And I missed my family, and she missed her family.”

And the Mexican big leagues don’t pay the absurd sums the American big leagues do. “I would’ve had to play 10 years in Mexico and be really frugal with my money for her and I to save up and be set for life. That’s 10 years with no kids, 10 years with no career.

“The pros and cons weren’t even close for me when I sat down and thought about it. And there’s no contract, so one injury, one bad month, and you’re gone. Every time I stepped into the batter’s box, I looked at it like that guy was trying to take food off my table.”

“It came as a huge surprise,” Vanier says of D’Alfonso’s revelation that he wanted to call it quits. “I was discontent up until the last year.”

To top it all off, the team retracted their offer with no real explanation – D’Alfonso and Vanier still don’t know what happened. “They went out of their way to make sure he signed this contract, flew him there, fed him, kept him up in a hotel for the preseason,” Vanier says, “and just took him down one night and said, ‘It’s not going to work out.’”

The two had made major adjustments for one another, and in the end, those adjustments brought them back to Westbrook. They arrived in mid-December, 2014.

In the nine and a half years since his high school graduation, D’Alfonso never lost touch with Eisenhart, so when D’Alfonso and Vanier returned to Maine – when D’Alfonso wanted to take on a new challenge and establish Triple Crown – he found an eager supporter in his former coach. Eisenhart believed so strongly in D’Alfonso, in fact, that he bankrolled the venture.

“The thing that was beyond the money for me, though, was how much he’s always believed in me,” D’Alfonso says of Eisenhart. “I love him like a brother, but I look up to him like a father,” D’Alfonso says. “Everything any man should aspire to be, I see in John Eisenhart.”

Triple Crown opened only a few months ago – Eisenhart and D’Alfonso rent space in an old middle school, North Yarmouth Memorial. The business has been so successful, however, that D’Alfonso has nearly repaid Eisenhart’s investment already.

“The first month I had 20 or so clients sign up, and every one has been a repeat customer,” D’Alfonso says. He looks to nurture the Academy, of course, but doesn’t expect to leave his day job in the immediate future. “My girlfriend and family have dealt with enough inconsistency.”

D’Alfonso runs hitting clinics and gives private lessons as well; his youngest prote?ge? at the moment is a seven-year old girl, and his oldest, a 25-year old college guy. “If somebody can swing – anything – I can teach it,” D’Alfonso says. “That’s how I feel. You can pick up a branch and I can teach you how to swing it.”

He also teaches fielding and throwing on request. “I primarily do hitting, but I absolutely won’t turn down an opportunity to help a kid grow in baseball, no matter what it is. If they ask me how to lead off first base, or they just want to know the proper way to catch a fly ball, I won’t turn it down.”

Triple Crown is online at http://www.triplecrownbaseballandsoftballacademy.com. The Bitching Mound can be found at https://thebitchingmound.wordpress.com.

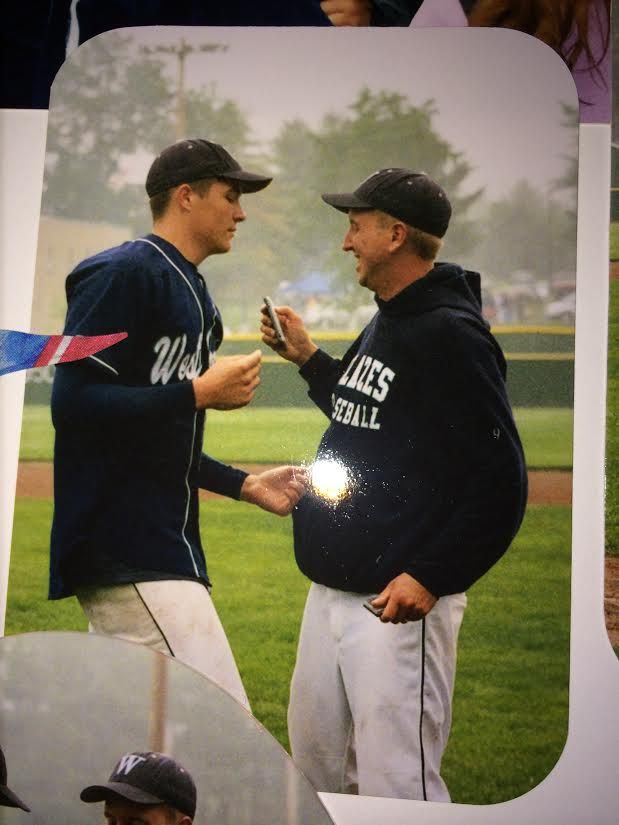

Anthony D’Alfonso (left), circa 2005, receives an individual award from – and trades hugs with – John Eisenhart, WHS baseball coach.

Anthony D’Alfonso (left), circa 2005, receives an individual award from – and trades hugs with – John Eisenhart, WHS baseball coach. Anthony D’Alfonso (left) crosses home in a Mexican-league game.

Anthony D’Alfonso (left) crosses home in a Mexican-league game. Angela Vanier (left) and Anthony D’Alfonso (right) gave up much for each other – and are happier for having done so.

Angela Vanier (left) and Anthony D’Alfonso (right) gave up much for each other – and are happier for having done so. Anthony D’Alfonso poses with his 2014 Homerun Derby trophy.

Anthony D’Alfonso poses with his 2014 Homerun Derby trophy.

Comments are no longer available on this story