Paris, Missouri, population 1,246 and falling: This is the hometown to which George Hodgman returned for his mother Betty’s 91st birthday. Two weeks stretched into two months. He thinks about leaving but cannot bring himself to get a flight back to New York.

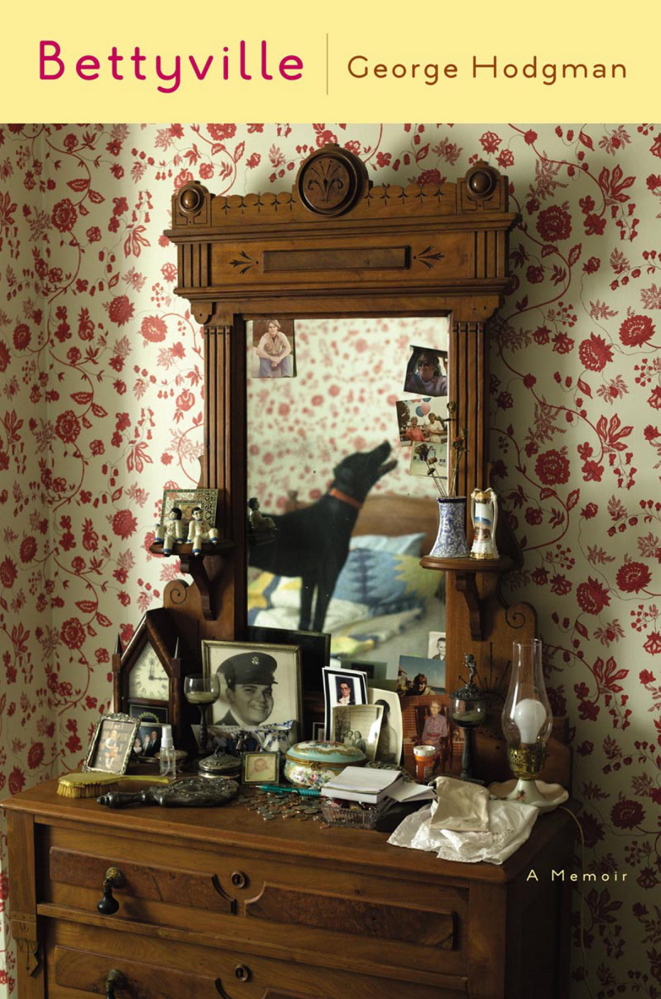

Hodgman does not make himself seem heroic. “I’m not a martyr,” he writes in his new memoir, “Bettyville.” “I’m just available, an unemployed editor relegated to working freelance.” As he puts it, he stays there, in the house with dusty antiques and dying rosebushes, to become his mother’s “care inflictor.”

Be not afraid that “Bettyville” is a story about elder care, because Betty Baker Hodgman would never stand for it. Even with dementia and lymphoma, Betty is very much full of life and never tries to be anyone but herself. “‘At least I’m out and out with my meanness,'” she tells her son. “‘I’m not a sneak. I hate a sneak.'”

Betty isn’t really mean, just direct and quick-witted – even if she struggles for words. A real tenderness runs through this poignant memoir, and its comedic qualities and sharp insights prevent it from becoming sappy. (The man at the IGA told George that his mother “came in here one day and said she could get fresher produce at an antique store.”)

After Betty loses her driver’s license – she drove into a ditch – she likes taking to the road with her son, although outings to places like “Waikiki Coiffures” can be an ordeal. “When dealing with older women,” writes Hodgman, “a trip to a hairdresser and two Bloody Marys goes further than any prescription drug.”

Hodgman has a way of seeing the absurdity of it all. When the lacquered bubble from “Waikiki Coiffures” isn’t entirely successful, a downcast Betty claims this is her worst yet, but he notes that she has not had what she considers “a successful hair appointment since around 1945.”

While Betty once shooed her son off, she now wants him close. He looks in her face and understands her anguish, aware that she is barely holding on and becoming more anxious, sometimes even terrified. The little things bother her – the misplaced address book, the uncooperative TV remote control or can opener, lost words. “Don’t leave me,” she says if he goes to bed before she does. Betty and Hodgman’s father, who died in 1997, never fully and explicitly accepted that their son was gay.

Betty may be afraid, but she will not speak of her fears. “She keeps her secrets,” Hodgman writes. “I keep mine. That is our way. We have always struggled with words.” Hodgman renders Betty fully – and on this journey home, learns that he is strong enough to stay the course with her in Paris.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story