EXETER — Adam Wintle sees too much of a good thing when he reads the electronic panel attached to the side of his $6 million anaerobic digestion system. An engine generates electricity by consuming 340 cubic feet of methane-rich biogas gas per minute. But another 200 cubic feet of gas is shooting up a pipe and burning off in a flare.

“We’ve got a lot of excess gas,” Wintle says. “That gas could be running another engine.”

The digester is essentially two enormous crockpots that cook a stew of cow manure and food waste at 100 degrees. Built just over three years ago, it is the largest anaerobic digester in Maine and among the largest in the United States. It produces enough electricity to power all the homes in a town the size of Boothbay Harbor.

The 1,000 milking cows at the adjacent Stonyvale Farm supply the manure. Hospitals, restaurants and grocery stores provide the discarded food.

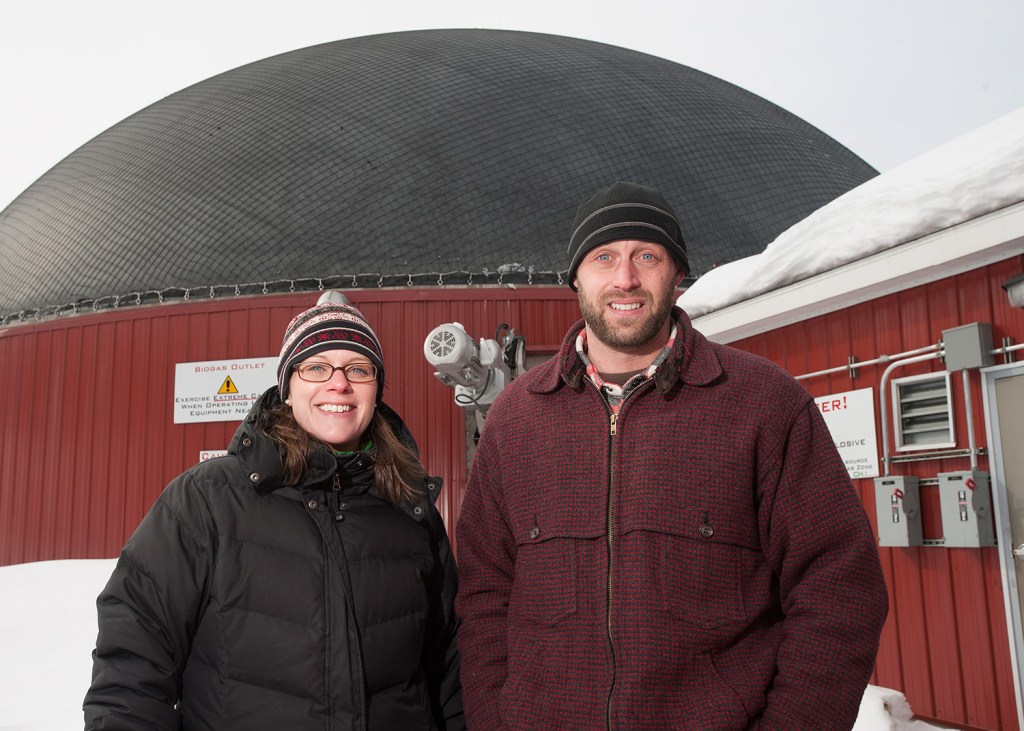

Wintle, 34, his brother, John, 37, and sister, Sarah, 35, are ambitious, and they enjoy the support of their major investor, Stonyvale Farm, the second-largest dairy farm in the state.

The Wintles plans to add two more engines and build two more 25-foot-tall, 400,000-gallon digester vessels – the concrete containers in which the slurry of manure and food waste is cooked. If construction of the $10 million project goes ahead, the expanded facility would operate more efficiently and generate 3 megawatts of electricity – three times as much as it produces today.

When completed, it will produce the same amount of electricity as produced by the 17 digesters in Vermont. Because the Vermont digesters use only manure, they can’t produce as much electricity as the Exeter facility. Manure keeps the digesters running smoothly, Wintle says, but it’s the food waste that makes them a powerful producer of biogas.

The major obstacle to the siblings’ expansion plans is getting enough food to mix with the manure.

About 20,000 tons of food waste get dumped into the digester annually, but a stream of 50,000 tons is needed to make the expansion project work.

“The choke hold on expansion is food waste,” Adam Wintle says.

To meet that need, the Wintles have launched an organics collection company called Agri-Cycle Energy. The company has agreements with Hannaford, Whole Foods and Wal-Mart stores in the region and also Massachusetts General Hospital and the World Trade Center in Boston to collect their food waste.

The company is competing with conventional trash haulers, which bury food waste in landfills or burn it in incinerators, and composting companies that collect food waste in food scrap collection trucks.

Adam Wintle says Agri-Cycle Energy charges about the same as the trash and compost companies, but it’s hard breaking into the business because those companies are doing everything they can to keep their customers.

“We have learned we have to go out and battle them,” he says of the competition.

FARMING ROOTS

The Wintles grew up in Augusta but spent their summers and weekends at Stonyvale Farm, where their grandfather, John Fogler, started a commercial dairy operation in the 1950s with 17 cows. They feel a connection with the farm, not just as a commercial enterprise, but because it’s part of their family history. Helping the farm become more efficient was part of the reason Adam Wintle first began exploring the biodigester idea in 2009.

The digester helps the farm become more efficient in two ways: It converts manure into a low-odor, liquid fertilizer that is easy to spread. And income earned from selling excess electricity to the power grid gives the farm a steady cash stream, mitigating the volatile nature of the dairy business.

“The digester is integrated into the daily rhythms of the farm,” Sarah Wintle says. “It’s really a community of people working for the good of both facilities.”

To pay for the upfront cost of the digester, the siblings secured about $3 million in grant funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the U.S. Treasury Department and Efficiency Maine. The Farm Credit of Maine provided $3 million in loans. The Wintles also won a 20-year contract to supply the power grid with electricity at 10 cents per kilowatt hour. The contract was awarded as part of a state renewable energy program administered by the Maine Public Utilities Commission.

Adam Wintle, a former commercial real estate developer, is the managing director of Biogas Energy Partners, the development company at the center of the enterprise. John Wintle, who holds a degree in bio-resource engineering technology from the University of Maine, oversees plant operations. Sarah Wintle is the “details person” who overseas business operations, particularly for the organics collection effort.

In addition to creating a larger digester, the Wintles want to build a commercial greenhouse next to the digester to take advantage of the excess heat and nutrients generated. The idea is to add yet another revenue stream to the farm.

The Wintles also want to capture some of the excess biogas and convert it to compressed natural gas to power their fleet of six trucks. The trucks travel around New England picking up food waste and bringing it back to Exeter.

Adam Wintle says he hopes to partner with Maine’s largest dairy farm, the Flood Brothers Farm in Clinton, to build an even larger digester system there.

But none of this can happen without more food waste.

Several customers are in Massachusetts, which has a new law that bans large commercial food waste generators, such as restaurants and hospitals, from burying their garbage in a landfill.

One new customer is Massachusetts General Hospital. An Agri-Cycle Energy truck visits the hospital six days a week to pick up discarded food from the hospital’s cafeteria and kitchen. “I never would have dreamed that my food would end up going to a farm in Maine and mixing with manure,” says Guillermo Banchiere, the hospital’s director of environmental services.

When manure decomposes, it releases methane – one the most potent greenhouse gases. So does food buried in landfills, says George Parmenter, manager of sustainability for Hannaford Supermarkets. The chain has 40 stores in Maine that send food waste to Exeter.

Parmenter says that the grocery chain tries to make sure its discarded food is put to good use. It donates still edible food for human and also farm-animal consumption. In the case of spoiled and expired food, the digester in Exeter is a welcome option, he says, because it transforms that food into electricity with little cost to the environment.

“Even if it’s bad food, it can have a life beyond us,” he says.

Packaging complicates the disposal of food waste. Each Hannaford store sends about 3,000 pounds of food waste a week to landfills because the food is packaged, and it’s too labor-intensive to remove, Parmenter says.

The Wintles say they can solve that problem. In May, they’re installing a $1 million machine that will extract packaging and other contaminants from food waste. They say the machine is critical for the company’s efforts to boost volumes of food waste needed for the expansion.

The machine means Hannaford can double the amount of food it sends to the digester, Parmenter says, and will be especially useful after power outages when large amounts of frozen and refrigerated products have to be thrown out.

AN APPETITE FOR WASTE

The nation is awash in wasted food, which costs a lot of energy and water to produce, Parmenter says. In the United States, 72 million tons of food are discarded each year, according to the Waste and Resources Action Program, a British group that advocates for reducing waste in the food supply chain worldwide.

Digester systems are not always the solution, though. They have huge startup costs and are prohibitively expensive in most states unless some grant funding is available, says Curt Gooch, who works as the environmental systems and sustainability engineer at the dairy program at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

Vermont subsidizes the construction of its digesters by using a utility-funded grant program that was created as a result of an insurance settlement after Vermont Yankee nuclear power plant was sold.

In Europe, where farm digester systems are common, various regulations provide subsidies, Gooch says. The systems benefit the farms, but society also benefits, he says, so the subsidy makes sense.

“The people who understand this know it’s a really good thing,” he says. “The economics are challenging. The key is to have that food waste.”

Besides producing electricity, the digester in Exeter produces two other byproducts – a liquid fertilizer that is sprayed on the fields where crops are grown to feed the cows, and an organic solid that is used as bedding for the cows.

“This is a completely closed system,” Adam Wintle says. “There is nothing wasted.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story