Bordeaux’s wines, Bordeaux’s geography, Bordeaux’s history, Bordeaux’s costs are all so complicated and intimidating, I go numb, I surrender – and I drink from elsewhere. I think I speak for millions of non-Chinese-oligarch sub-septuagenarians when I say, “Whuh?” Not to mention, “Why?”

In wine, Bordeaux used to be the start, middle and end of the story. Perhaps there were brief tangents to white Burgundy or German riesling, but for the most part, from the dawn of the Industrial Revolution up to Sid Vicious’ day, drinking wine earnestly meant drinking Bordeaux.

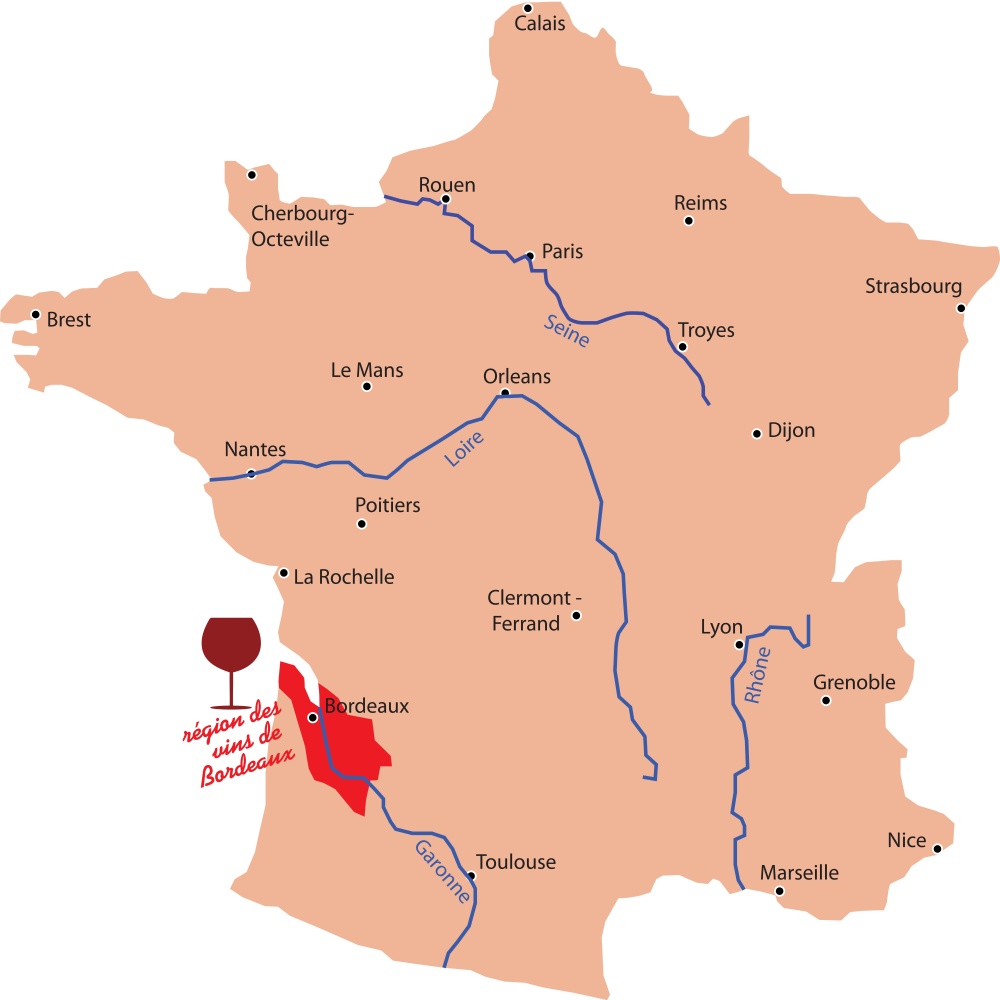

It was relatively affordable to do so, and there were so few available alternatives. The question of what to drink was occasionally “Bordeaux or Rhône?” but more often was “Médoc or Pomerol?” circumscribed entirely within Bordeaux’s boundary lines.

Entertaining that question, whenever I’ve encountered it, has felt more like a test than a conversation. Before one is invited to have experiences with Bordeaux, one is urged to establish a base of knowledge, form opinions about it and then, ultimately, obey it on its terms. Bordeaux often seems to be a performance of wine more than an expression of wine, an arena of combat rather than a place to play.

Minds change, markets change, tastes change. Wine used to be drunk exclusively by the rich, and Bordeaux met their needs. Once wine became a more common beverage, and as people and information grew increasingly mobile, the field expanded exponentially, far beyond Bordeaux’s borders. And for a long time, Bordeaux seemed not to care. On went the protectors of the brand, cultivating the “luxury” image, courting millionaires in emerging post-Communist economies, hiding the security code to the gate.

So, y’know, sour grapes. Many of us who grew up during a time of Bordeaux’s diminishing stature said, effectively, We don’t need no stinkin’ Bordeaux. Influential sommeliers called it fusty. Boomers found that they preferred the fruitier American expressions of cabernet sauvignon and merlot anyway. After years of wars and cultural macho nonsense and Robert Parker’s hegemony, sensitive poet types gathered the guts to drink Burgundy and Muscadet out in the open. Graphic designers created wine labels that said “Malbec!” or “Look at this Kangaroo!” or “Sexy Bitch!” instead of relying on a pencil drawing of a château. And young’uns didn’t have the scratch for Bordeaux, so they invented craft beer and Barolo. There you have it: the history of Bordelaise ignominy in one sketchily truthy paragraph.

Yet for all the reasons one is forced to remain a Bordeaux outsider, for all the alternatives one is offered, for all the reasons to roam, something calls. If the lines of Bordeaux’s maps are so bewildering, they must refer to something real on the ground. If the hierarchical classification of “growths” that dates back to Napoleon is so rigid, perhaps the soils and aspects of various châteaux deserve it. If the wines cost so damn much, maybe the wines give so damn much.

The wines themselves beckon as well. Not all of them do – not nearly all of them. But it is possible to find approachable, enjoyable, reasonably priced wines of character and distinction from Bordeaux. I’m sure that if I knew a lot more than I do about the region, this wouldn’t be so much of a shock. Bordeaux’s epistemology is so arcane that it almost requires specialized focus. I don’t have that; I have a generalist’s roving spirit.

I’m pleased to report, though, that by bringing a personal, emotional perspective to bear on a category of wines that would seem to reward collective approval and the intellect, I have succeeded in finding wines that elicit actual emotion. It turns out that in responding to Bordeaux I wasn’t caught between fight or flight; I could choose the middle path of feeling.

For this to work, I was lucky to have the deck stacked in my favor, in the form of the 2010 vintage, widely appreciated for its beguiling mix of direct likability and long-term potential. Bordeaux’s 2009s were initially praised for their power and fruit-crazy drink-now forwardness, but that estimation faded somewhat as tasters acknowledged that such traits were unlikely to last as the wines aged.

Most of the 2009s I’ve tasted have just been too blowsy and blinged. In the 2010 wines, there’s a rich vein of black fruit, but it’s tempered by more mineral tones and better structure, the straight lines in harmony with the curves.

I usually favor the Right Bank, that warmer region in Bordeaux’s eastern section, north of the Dordogne River, whose clay-based soils are best suited to merlot. In the gravel-based vineyards of the Left Bank, west and south of the Gironde River, cabernet sauvignon is king. That famously toughened varietal is often simultaneously too fruity and too tannic before time marries its poles. In the 2010s, both sides of the rivers fascinate me.

Merlot is deceptively fascinating. Its fruit flavors are softer, and overall its wines sing more quietly. This was taken to an extreme in pre-“Sideways” California, where merlot was used to make wines so inoffensive and inconsequential that a backlash ensued. But when merlot is pushed to excel, its songs turn incantatory. Good merlot wines deliver me to Middle Earth, a pleasantly dim and disorienting alternative to the raw above-ground power of good cabernet.

In Bordeaux, though, the blend is all. Merlot and cabernet sauvignon are blended with cabernet franc, and sometimes small amounts of malbec and petit verdot (and at this point rarely, carménère). Bordeaux’s reputation as a wine to age comes in part from this heady grouping of grapes, which need time in small barrels, and then in bottles, before they can play nice together.

In 2010, the blend is already happening, and the Left Bank wines as well as the Right are ready. The wines listed will all happily reward patience as they lie on their sides in your basement, but they are already exuberant and often deep, their richness kept in check by strong non-fruit characteristics. They are dense but refreshing, woodsy and subtly spicy, as Bordeaux should be, yet unafraid to draw your attention with plump, dark fruit.

These Bordeaux don’t strike fear into my heart, they don’t spur class-war fantasies, they don’t make me wish I had gotten my Ph.D. They are satisfying, they are balanced, they are real. They invite the pouring of a second glass. And most important, they feel relevant.

Château d’Arcins 2010, $22. A potent, medium-full-bodied cabernet-heavy blend from the Haut-Médoc. This is a textbook intro to some of Left Bank Bordeaux’s primary traits: cedar, a raw sort of woodsiness that will mellow over time (even over the course of a meal), and black fruit, both fresh and dried.

Château Meric Graves 2010, $18. More black fruit, including the classic currants, here counterposed by a feeling of the ocean rather than the d’Arcins’ forest. There’s a seaside, kelpy salinity, and a vinous, sappy quality. At its best, Bordeaux’s ability to be both profound and refreshing is unparalleled. See why with this.

Château Beausejour Pentimento 2010, $23. Classic old-school St.-Emilion, from the Right Bank, with the spice and red fruit of merlot and the peppery zip of cabernet franc. It’s bold and zippy, but juicy enough to swallow up sausages or a rich meat sauce.

Château des Landes Lussac St-Emilion 2010, $20. Another big, spicy Right Bank wine, 80 percent merlot, though with some of the purple-black fruit and hardwood traits of the Left. Already lush and dense, this coiled wine will be fascinating to watch over years of aging.

Joe Appel works at Rosemont Market. He can be reached at:

soulofwine.appel@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story