Gov. Paul LePage’s proposal to eliminate methadone as a MaineCare benefit could kick thousands of patients out of clinics, disrupt their treatment plans and threaten the existence of the clinics, health experts say.

But the proposal – potentially the first of its kind in the nation – would need federal approval to become reality, Medicaid officials told the Portland Press Herald.

LePage administration officials counter that another medication, Suboxone, is a better choice for patients. Suboxone is similar to methadone but is used less widely. Medical professionals say it cannot replace methadone for many patients because the drugs have different effects on the brain.

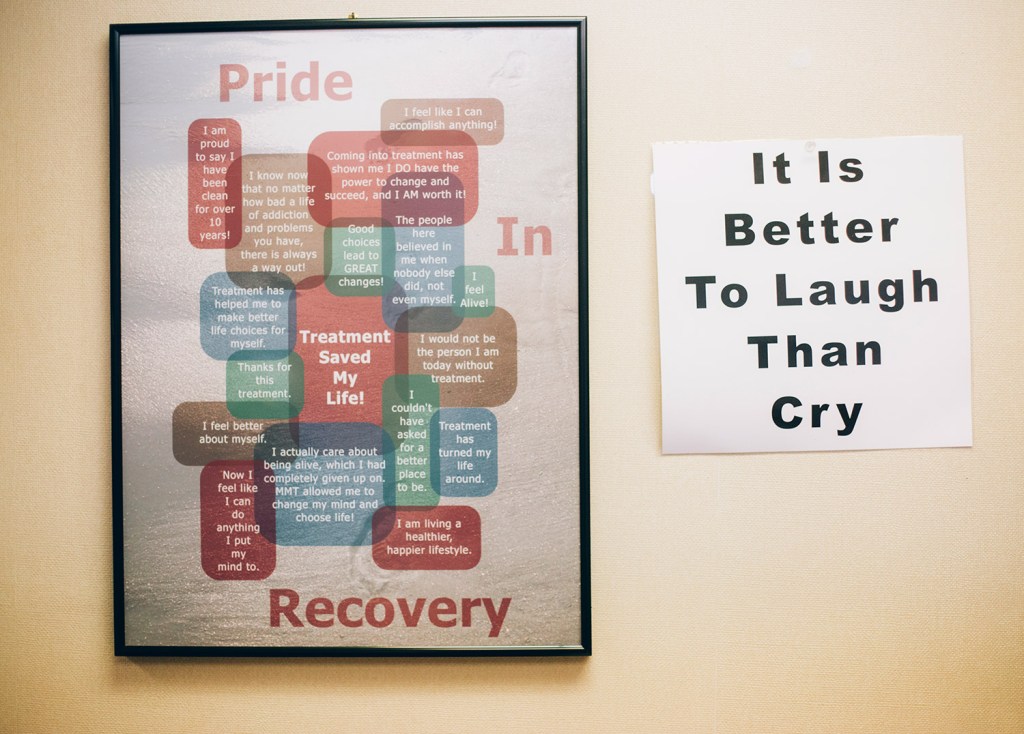

“This is the first place I got the help that I needed. This has been a lifesaver,” Amy Alexander, 50, of Brunswick, said of the Westbrook methadone clinic she attends. “If I stop coming here, I have no doubt I would use again.”

To end methadone reimbursement for people like Alexander, a MaineCare patient who is a former prescription opiate addict, the governor would need federal approval, and the state Legislature would have to pass his budget with the methadone initiative intact.

Whether U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services officials would sign off on such a plan is unknown, but the proposal would be closely scrutinized, Medicaid officials said.

Richard McGreal, associate regional administrator for Medicaid, said Thursday that the plan would be evaluated based on the access that Medicaid patients would have to their treatment and medications. He said the LePage administration has not yet sent its plan to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, so he could not comment on potential details of the federal evaluation.

“If the state submits a plan, one of the things that we would be looking at is whether the medications they would be using would be on the same level as methadone. Is it as effective?” McGreal said.

Dr. Meredith Norris, a Kennebunk doctor who prescribes both methadone and Suboxone, said Suboxone is not effective for some patients for a number of reasons.

“If you have taken large volumes of opioids, your body chemistry changes and Suboxone simply isn’t going to work for you,” Norris said. “People are going to switch to heroin.”

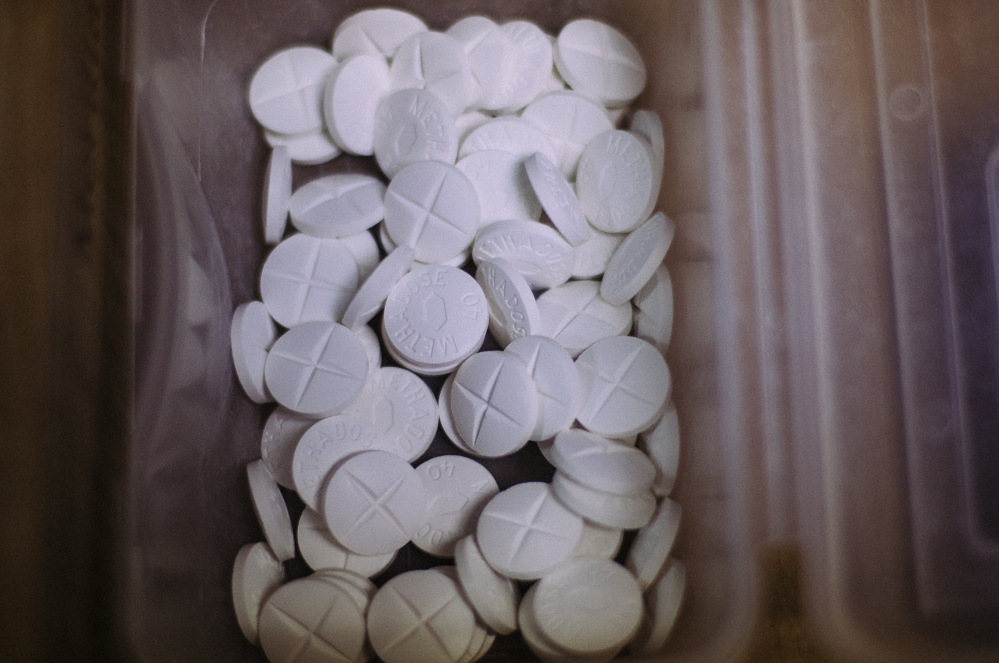

Suboxone is a take-home drug, while methadone is usually taken in liquid form at a clinic, Norris said. Many addicts are not responsible enough to successfully take medication at home, she said, and taking methadone under the eye of a medical professional is a way to ensure they receive proper treatment. Norris works one day a week at the CAP Quality Care methadone clinic in Westbrook where Alexander receives treatment.

DHHS: SAVINGS PLUS BETTER TREATMENT

If the state eliminated methadone coverage, MaineCare patients who need to continue taking it would have to pay about $100 per week out-of-pocket, which would be nearly impossible for those on limited incomes, industry officials say. Many of the state’s nine methadone clinics – where more than 60 percent of about 4,500 total patients are typically on MaineCare – would be in danger of closing, said Portland attorney Jim Cohen, who represents the methadone clinics.

Mary Mayhew, commissioner of Maine’s Department of Health and Human Services, said in a written statement that Suboxone is superior to methadone for patients. The state would save about $750,000 per year by eliminating methadone coverage for MaineCare patients.

“Transitioning recovering addicts from methadone to Suboxone is just one of several initiatives within the governor’s budget proposal designed to strengthen and encourage the use of primary care among Medicaid recipients. Taking this treatment approach means lower costs and better health outcomes. For addicts, it also means a safer and more holistic alternative to methadone treatment as they travel the road to recovery,” Mayhew said in the statement.

Mark Parrino, president of the New York-based American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence, said states can deny Medicaid reimbursement for all outpatient opioid treatment, but he questioned whether it would be legal for states to pick and choose what medicines can be reimbursed. Seventeen states do not reimburse for any opioid treatments under Medicaid.

“What the state of Maine is considering doing is getting involved in the practice of medicine,” Parrino said. “It doesn’t make any common sense.”

Methadone has been studied for 50 years and found to be effective and safe, and that for many patients it’s the best treatment option, he said.

STATE MAKING MEDICAL DECISIONS?

DHHS spokesman David Sorensen wrote in an email response to questions that “methadone treatment for addiction cannot be reported to the state’s prescription monitoring program.” He said that means primary care doctors may not know if their patients are attending methadone clinics.

“National research has long underscored the importance of an integrated approach to physical and behavioral health. The free-standing methadone clinics are counter to this effort and exacerbate the fragmented delivery system,” Sorensen wrote.

But Norris said that substituting Suboxone for methadone is not a medically sound practice for many patients because the drugs have different effects on the brain.

“Are we going to be making these decisions based on opinion or on scientific evidence?” Norris said. “I am deeply uncomfortable in a situation where the state government is in the position of making medical decisions for patients. Would the state tell patients what medication they could take for their heart conditions?”

Most doctors won’t prescribe Suboxone for methadone patients who take more than 30 milligrams of methadone per dose, and the clinic average is about 110 milligrams, said Kathy Alarie, a nurse and program director at CAP Quality Care.

“Methadone gives people their lives back, and allows them to raise their children, go to work and be a contributing member of society,” Alarie said.

In 2012, the state Legislature approved a two-year maximum for methadone treatments, but the treatments can continue beyond that if a doctor determines it’s medically necessary. Alarie said in many cases, the treatment is deemed necessary and is continued beyond the two years, although there are some cases in which a patient can taper off methadone.

SHERIFF BACKS METHADONE TREATMENT

Kennebec County Sheriff Randall Liberty is opposed to eliminating methadone treatment as a MaineCare benefit because he has “no doubt” that it would result in people returning to using street drugs, and people committing crimes, such as robberies and prostitution, to buy drugs. He said 40 percent of the Kennebec County jail population is incarcerated because of opiate addictions, and the jail becomes a revolving door for addicts, he said.

“We have to stop judging and punishing, if it’s a medical condition, and get these people the treatment they need,” Liberty said.

For Alexander, the clinic has allowed her to make friends, volunteer and live a normal life, although she can’t work because of another medical condition.

“I can take care of myself now. I have control of my life, and I’m not making bad choices,” she said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story