A year ago, the governors of Vermont and Maine both made public pleas for action against New England’s rising heroin problem.

Peter Shumlin, a Democrat who devoted his entire State of the State address to the subject, called for a response centered on treatment, and, after spending $6.7 million in the last year, Vermont has seen a significant rise in the number of addicts in recovery.

Paul LePage, a Republican, called for increased funding, too, but his $2 million-plus proposal would have added more drug enforcement agents, judges and prosecutors, not more treatment options. His bill was changed by lawmakers to better balance treatment and enforcement, but it ultimately died when funding could not be found.

The Maine governor’s plan, in a slightly different form, returns in his latest budget proposal, which includes more than $8 million for the criminal justice system but is light on support for treatment initiatives necessary to stop the rise of opiate addiction.

The Legislature will need to remedy this imbalance by putting forth a plan that provides law enforcement the tools it needs to keep communities safe, while also giving the thousands of Mainers seeking help a path to sobriety that is proven to work.

As it stands now, Maine’s answer to the challenges poised by heroin addiction falls far short. About 4,800 Mainers sought treatment for opiate addiction in 2013. That represents a 15 percent increase over three years that has been fueled entirely by the rapid rise in popularity of heroin, which has replaced more expensive and scarce painkillers as the opiate of choice.

At the same time, the number of beds available for inpatient treatment – perhaps the most effective way to combat opiate addiction – has stayed level at about 200, while overall funding for treatment has continued to fall.

Maine also has the lowest per-patient payments in the United States for clinics that treat addicts with methadone, a medication administered at standalone clinics that alleviates the symptoms of opiate withdrawal. LePage’s budget proposal further cuts methadone funding by more than $1.5 million, giving up $2.7 million in federal matching funds.

Instead, the budget increases reimbursement rates for primary care physicians, who can prescribe Suboxone, a methadone alternative, and offer patients a more holistic approach to health at the same time.

Suboxone is considered safer than methadone, and it can be reported to the state’s drug monitoring program, another plus. Nationwide, its use now greatly exceeds that of methadone.

But prescribing physicians must be trained by the Drug Enforcement Administration, and there are limits on the number of patients one can serve. That has led to a shortage of doctors who can and will prescribe the drug, in Maine and across the country.

In any case, drug replacement therapy, whether it be methadone or Suboxone, must often be coupled with other treatments, such as those in behavioral and mental health. And without a comprehensive, well-funded approach to treatment, addiction will continue to flourish.

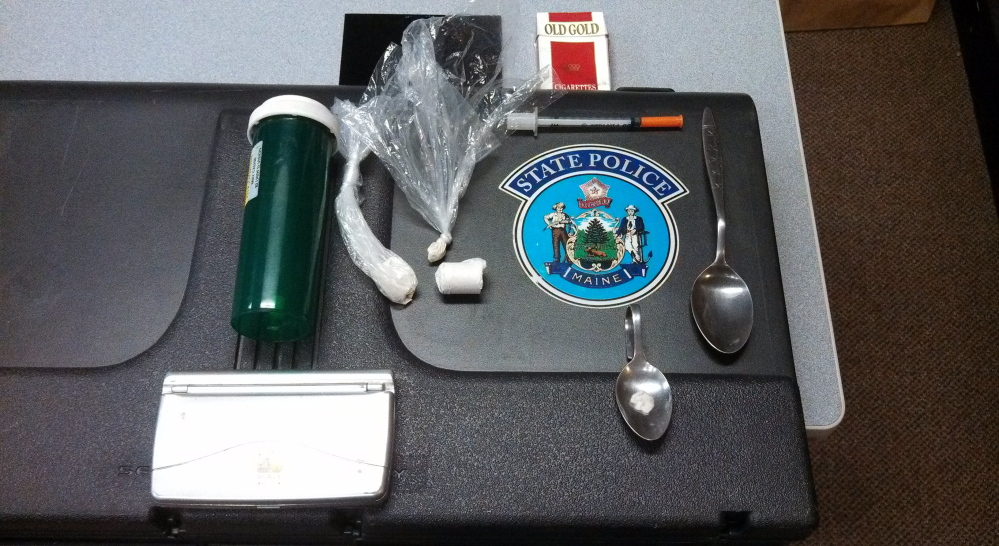

It’s that addiction that is fueling the rise in heroin abuse, just as it fueled the prescription painkiller crisis. Plentiful, powerful OxyContin drove that earlier epidemic, until the pills became more difficult to acquire. Users then turned to cheap heroin, and Maine became a target for out-of-state traffickers.

Police and prosecutors need the resources to address that influx of professional drug dealers. But as long as there is widespread opiate addiction, the demand will be there as well, and no amount of arrests will erase it.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story