BATH — Walking through Bath Iron Works’ sprawling shipyard, it’s difficult to reconcile the sight of thousands of workers building five massive Navy destroyers with the talk about potentially huge job losses in the not-too-distant future.

Three destroyers – one nearly complete and in the water, one assembled, and one still in segments – dominate the outdoor yard. Inside a cavernous hall, welding and grinding sparks fly against a backdrop of clanging metal and the whir of heavy machinery as workers assemble sections of two more multibillion-dollar warships.

Hundreds of new hires have pushed BIW’s employment rolls to their highest levels in years. Yet leaner times may be just over the horizon at BIW, a manufacturing powerhouse on Maine’s tourism-dependent coastline.

Managers at the General Dynamics-owned shipyard are warning that less Navy work in the years ahead could eliminate as many as 1,200 jobs. The prospect has BIW feverishly looking for ways to cut costs, giving the yard a better chance of landing a “must win” contract to build Coast Guard cutters.

This fall, BIW President Fred Harris alarmed the leadership of the largest union by beginning the formal process to outsource fabrication of some ship components – electrical panels, lockers and tables, to name a few – that are now made by unionized BIW employees. Finding efficiencies, Harris insists, is critical to not only beating two leaner, nonunionized shipyards vying for the Coast Guard work but also to better position BIW for future Navy work.

“We are a shipbuilder. We know how to build a superstructure,” Harris said while seated in his office filled with depictions of the 500- to 600-foot destroyers built in Bath. “But there are many things that we build here in this shipyard that we probably would be better off having someone else build for us.”

To Harris, the very future of Bath Iron Works hinges on whether it can remain competitive in an era of tight federal budgets, a shrinking military force and perennial political discord in Washington. But while Harris has been praised for his willingness to listen to workers’ suggestions on work-flow efficiencies, his outsourcing proposal is causing friction with the largest union.

“We know we have to be cost-efficient. The union is 100 percent behind trying to reduce costs,” said Jay Wadleigh, president of the Local S6 chapter of the Industrial Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers of America. But as union officials review 1,250 pages of outsourcing documents and nearly 2,500 time studies provided by the company, Wadleigh sees a flaw in the proposal: “There is nowhere near the savings that the company thinks is there.”

According to Harris, the stakes go far beyond the 1,000 to 1,200 jobs that could be shed unless BIW’s cutter design bid – to be submitted in early 2016 – is accepted by the Coast Guard.

“There has probably not been a time in Bath’s past where it’s more critical for us to be more efficient than ever before,” Harris said. “I worry about the nation’s resolve to continue to build ships long after I’m gone (from BIW). So we have to set the foundation here that we’re the guys left to build those ships and not other shipyards in the U.S.”

Union leaders insist they are on the same page when it comes to lowering costs but say that giving laborers accurate designs and ensuring materials are on hand when needed, not outsourcing, are the solutions.

While union officials are still analyzing the proposals under the formal outsourcing process spelled out in the labor contract, Wadleigh said one reason the cost-savings are negligible is that BIW workers must often “rework” outsourced components in order to meet the shipyard’s higher standards, thereby eliminating any savings.

“We understand that the key to winning contracts, and the key to having a vibrant and healthy union, is to get the costs down,” Wadleigh said. “We just don’t agree with the way he is going about it.”

HIGH STAKES, UNPREDICTABLE TIMES

With just under 6,000 employees and a payroll of $360 million, BIW is one of Maine’s largest private employers with an economic impact that extends far beyond its location on the banks of the Kennebec River.

BIW spent $64 million with 345 companies located in 12 of Maine’s 16 counties in 2014. The bulk of that money – $40 million – flows to small businesses, according to figures provided by the company.

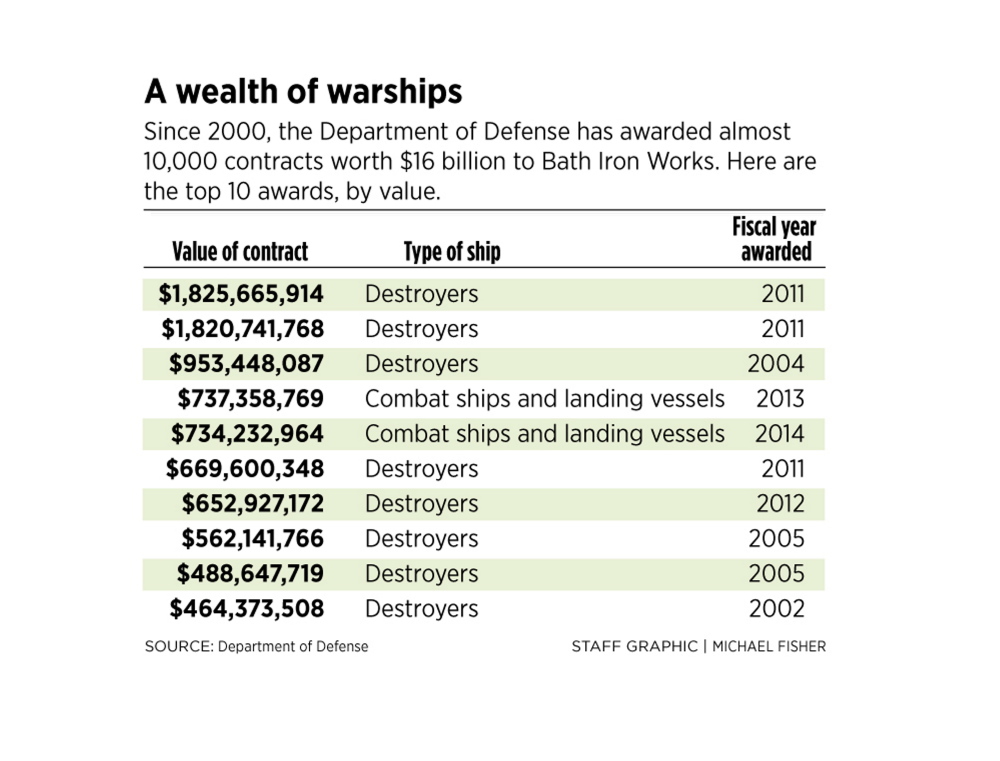

Yet this multibillion-dollar Maine company currently has only one buyer: the U.S. Navy. That’s a worrisome dynamic when the only thing predictable about federal budget levels is their unpredictability.

From 2013 to 2014, the Navy reduced the number of destroyers it anticipates purchasing over the next 30 years from 70 to 65. Of more immediate consequence, the Navy warns that it may be forced to cut another three destroyers by 2019 unless Congress lifts the spending caps established under the budget deal that gave rise to the recent “sequestration” budget cuts.

“It is tough for anybody to find money in Washington, and it is going to get tougher yet,” Harris said.

Navy destroyers take years to build and are contracted out to BIW and its competitor, the Huntington Ingalls shipyard in Pascagoula, Mississippi, years in advance.

That’s why BIW knows that after the third and final DDG-1000 Zumwalt-class “stealth” destroyer floats down the river sometime in 2018 or 2019, the shipyard is likely to receive one new destroyer contract per year for the foreseeable future, based on the Navy’s own plan.

And that’s where the Coast Guard contract comes in.

BIW is one of three shipyards competing to land a contract potentially worth $10 billion to build up to 11 offshore patrol cutters, or OPCs, for the Coast Guard. While BIW hasn’t built Coast Guard boats in generations, the cutters would be similar in size to the Navy guided missile frigates the shipyard churned out alongside destroyers for years.

The two Gulf Coast shipyards competing against Bath for the Coast Guard contract – Bollinger Shipyards in Lockport, Louisiana, and Eastern Shipbuilding in Panama City, Florida – are smaller, more diversified, nonunion yards located in a lower-cost area of the country. In addition, Bollinger already builds fast-response cutters for the Coast Guard as part of a 34-ship contract.

“I think the Navy would tell you that BIW is the best builder of surface warships in the Western Hemisphere but it is not in an advantageous position for cost,” said Loren Thompson, a naval policy and acquisition expert with the Lexington Institute in Virginia. “It is up a river, in a cold climate and in a part of the country with a strong regulatory environment.”

The Coast Guard builds fewer ships and has a tighter budget than the Navy. Meanwhile, Gulf Coast shipyards have proven highly capable of producing cutters for the Coast Guard.

If either Bollinger or Eastern Shipbuilding can prove it can build the requisite quality ship at a lower price, Thompson added, “then the fact that Bath builds a better ship is probably not enough for BIW to win the competition.”

“It’s going to be tough,” said Guy Stitt, president of the naval analysis firm AMI International, when asked about the cutter deal.

“But Bath has been dealing with competition from the Gulf Coast for quite a while and I think what Bath has been able to do is demonstrate good quality” at a reasonable cost, Stitt said. “Bath is very good at the complex vessels. The challenge is: That scope of complexity is not required in the OPC.”

Robert Socha, executive vice president for marketing and sales at Bollinger Shipyards, declined to comment on the OPC competition but noted that his yard has been building Coast Guard cutters since the 1980s. Also, about one-half of Bollinger’s work is building tugs, barges and other vessels for the private commercial sector, which is more price-conscious than the military.

“One of our biggest attributes is our versatility with both government and commercial work,” Socha said.

Asked how Bath can compete against the other yards, Wadleigh, the Local S6 presdient, had a blunt response

“We’re better than them,” Wadleigh said. “You just have to be more efficient than them and you have to be more productive than them. There isn’t a shipyard out there that has the years of experience that we have.”

BATH’S HIGHER STANDARDS, COSTS

Shipbuilding began at BIW in the late 1880s as workers churned out wooden vessels both for the Navy and the private sector. During World War II, BIW produced more than 80 destroyers – a rate of one every two weeks.

The shipyard last built commercial vessels in the 1980s when the federal government helped subsidize commercial work at American yards. Some major Navy shipbuilders – including Huntington Ingalls and General Dynamics at its NASSCO yard in San Diego – also build commercial vessels. But the quality standards and complexity of Navy warships is so much higher that it is a challenge to meld the two.

Stitt gave the example of welders who may have to make three “passes” over a joint for a military ship but only two passes for a commercial vessel. Over the course of building a huge ship, that adds up to a lot of passes and man-hours, he said.

“They actually have to cut the yard in half and segregate the work,” Stitt said. “One side of the yard becomes very cost-conscious and one half is very quality-conscious.”

Harris, who helped bring more commercial work to NASSCO as that yard’s president, said BIW “would have to get much, much more efficient.”

For the time being, Harris is focused on reducing costs to become a Coast Guard yard as well as a Navy yard. Having the cutter contract, Harris said, means BIW would be able to reduce its overhead for the next round of DDG-51 destroyer contracts.

During the last round of DDG-51 bidding, BIW’s per-ship price was more than $50 million higher than Huntington Ingalls’ price, according to shipyard officials. The Navy awarded five destroyers outright to the Mississippi yard and four to BIW with the option for a fifth ship pending funding, which has since been authorized.

But according to BIW officials, the shipyard was a few percentage points away from losing that fifth ship to Huntington Ingalls altogether.

“On the last DDG-51 bid, we lost and we lost heavily or badly,” Harris said, referring to the price difference per ship between the Bath and Pascagoula shipyards. “And we have to be in a position to overcome that. We have to be in a position to offer the government a price that is competitive.”

A SMALLER, MORE COMPLICATED FLEET

Today’s Navy fleet is roughly half the size of a few decades ago, but each new ship is vastly more technologically advanced – and expensive.

In 1987 at the tail end of the Cold War, the Navy had 568 “battle force” ships patrolling the oceans to counter the perceived global threat posed by the Soviet Union. As of August 2014, the U.S. fleet was down to 290 battle force ships, a reflection of both geopolitical changes and more advanced, precision weaponry. The Navy’s current 30-year plan envisions a fleet of 306 ships.

At the same time, today’s high-tech ships carry much higher price tags. The DDG-51 Arleigh Burke-class destroyers that have been the workhorse of the Navy for decades cost more than $1.5 billion apiece. The three Zumwalt-class “stealth” destroyers – the largest and most technologically advanced destroyers in history – are expected to set the Navy back roughly $4 billion each.

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office paints a bleak picture for shipbuilders in a report that raises doubts about the Navy’s ability to achieve its long-term goal.

In a report to lawmakers this month, the CBO predicted the Navy would have to spend billions of dollars more per year than the Navy estimates to build all of the new ships and submarines it expects to need over the next three decades. Construction of a dozen Ohio-class submarines – a major component of the country’s nuclear strategy – is projected to cost between $79 billion and $92 billion alone.

An alternative build-out scenario compiled by the CBO forecasts the Navy could afford just 45 new destroyers rather than the 65 proposed in the 30-year plan.

“CBO’s estimate of $20.7 billion per year for the full cost of the Navy’s 2015 shipbuilding plan is 32 percent higher than the $15.7 billion the Navy has spent on average per year for all items in its shipbuilding accounts over the past 30 years,” the CBO report reads. “If the Navy’s future funding for shipbuilding is in line with its past funding, the Navy will need to reduce substantially its new-ship purchases relative to the number called for in its 2015 plan.”

Those prospects concern BIW’s Harris.

“So that worries me – that we might be in a position where there are fewer ships and the government decides that it is going to buy not 10 (destroyers) going forward but only five, or one a year, and then it is probably a winner-take-all competition,” Harris said. “We don’t want that to happen, but we better be in a position to win it.”

Of course, this is not the first time BIW has faced potentially massive job losses.

Exactly 10 years ago, the secretary of the Navy began exploring using only a single shipyard to build destroyers. Members of the Maine and Mississippi congressional delegations led the fight to defeat the proposal because of potential job losses in their home states. A year later, Hurricane Katrina severely damaged the Pascagoula shipyard, bolstering arguments for two facilities.

In fact, the threat of significant layoffs arises so often, said the Local S6 union president, that it can become a “boy who cries wolf” situation for longtime shipyard workers.

“We always have to pick up the pace and work a little harder because there is always some crisis just around the corner,” Wadleigh said. “Many of them have been real (crises) but never materialized. … But that sits in the back of your mind. ‘Oh, I’ve heard this before’ and people become numb to a degree. Not everybody, but some.”

Wadleigh said the current crisis could be the most real yet, however.

“They are saying it is a must-win,” Wadleigh said of the Coast Guard contract. “We have to take them at their word at this point. It would certainly be nice to win.”

LOOKING FOR A CONSENSUS

In the meantime, BIW management and union leaders are about halfway through the process of analyzing the company’s outsourcing proposals. The process, as laid out by the National Labor Relations Board, states that if the two sides reach an impasse, the issue will go to an “accelerated arbitration process” to decide whether the company’s cost-savings estimates justify outsourcing.

For months, rumors circulated that BIW planned to outsource some work to firms in Mexico. Harris insisted that won’t happen – an assurance he also made to U.S. Sen. Susan Collins of Maine, who became involved at the behest of the unions.

“But we will try, in accordance with the agreement, to work with the union to outsource those things to other American companies that we can find that can do the work and do it affordably, much more affordably than we do,” Harris said.

Wadleigh credits Harris and other managers for encouraging more shipyard workers to offer their own efficiency proposals. Under a pilot project, the union has already identified some potential cost-saving measures by working with a manager who is well-respected by workers in the yard.

Part of the challenge, Wadleigh said, is that many veteran workers have suggested efficiency and cost-cutting improvements to management in the past only to see them ignored.

“I’m cautiously optimistic that the company will back off a lot of these (outsourcing) proposals when they see the cost savings are not there and that we can find another way to try to save money that would sit better with our membership and still get us where we need to be,” Wadleigh said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story