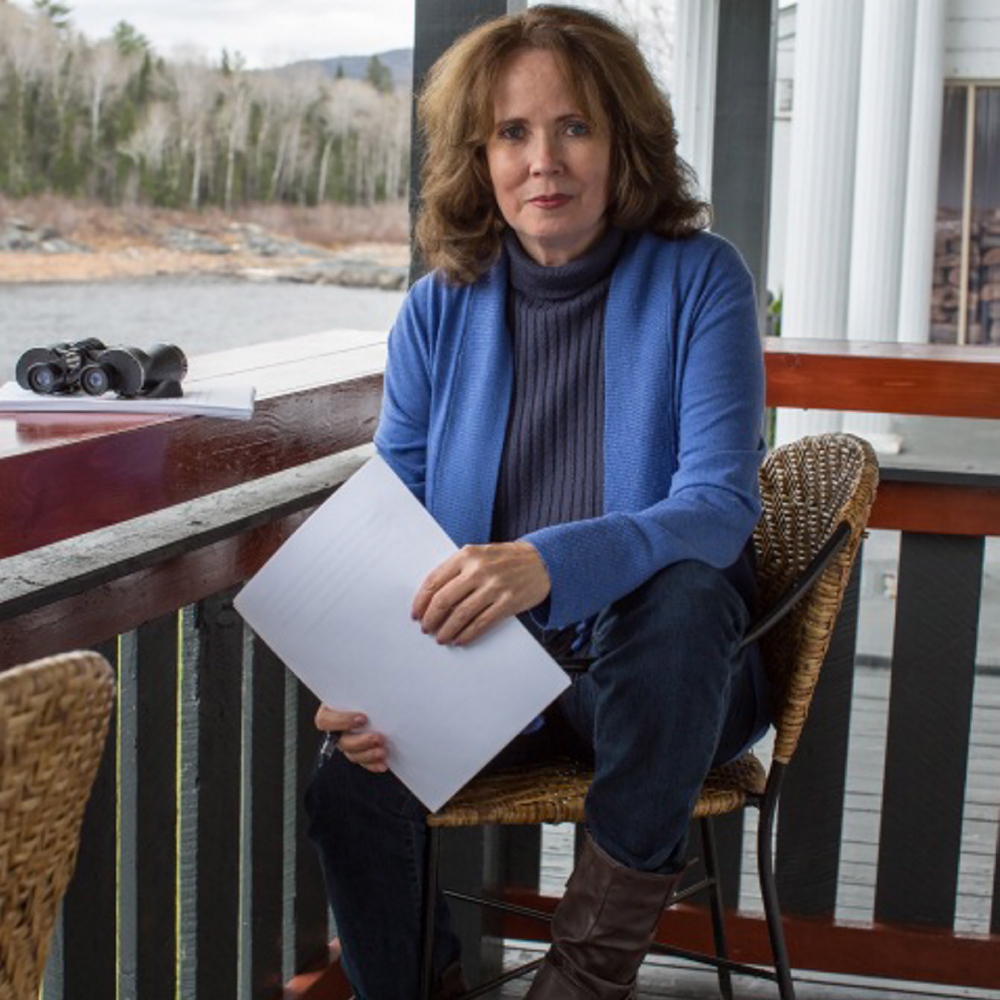

It has been a busy year for Maine novelist Cathie Pelletier. Her entire backlist of novels was printed by a new publisher, Sourcebooks Landmark. Her novel “A Year After Henry” came out in August. She has just released “The Secret World of Mr. and Mrs. Santa Claus” under her pseudonym, K.C. McKinnon, published by her new book press, Ethel Books. And, if that’s not enough, she’s making tracks before Christmas all over Maine promoting the book and the new press, which is named after her late mother.

Pelletier’s backlist includes the fabulous Mattagash stories, set in a small, isolated fictional hamlet, focusing on a cast of characters very much like those in Allagash, Maine, where she grew up. Pelletier’s roots in Allagash go deep, seven generations back to ancestors who poled their way up the St. John River and founded the community.

Pelletier, who describes herself as a “rebel” and chafes at what she calls society’s “rituals,” left Allagash when she was 16. She lived away for years – 30 years in Nashville and several in Canada. Five years ago, she and her husband, Tom Viorikic, moved back to Allagash.

“A Year After Henry” is set not in Mattagash but in fictional Bixley, Maine, “somewhere north of Bangor.” The challenge of fixing its location, she explained, was deciding where to put a community of 25,000 in northern Maine. Though Bixley is clearly a city in her mind, Pelletier brings to it her trademark brilliance at capturing the lives of characters in a small place. Few writers do it better than her.

The novel focuses on a handful of characters whose lives have been upended by the death, at middle age, of Henry Munroe. Between his death and his memorial service a year later, we see the long shadow this perennial golden boy casts over these characters’ lives, both before he died and after: parents, wife, son, but especially Evie Cooper, his erstwhile lover, and Larry, his older brother. Henry, in essence, is a protagonist in absentia, a ghost who haunts them still.

The story has momentary resonances of the classic novel “Winesburg, Ohio” and the play “Our Town,” where the reader is allowed glimpses “beyond the veil” that shields the living and the dead.

“The Secret World of Mr. and Mrs. Santa Claus” is a niche book, according to Pelletier. Major publishers didn’t know how to peg it, so she took it upon herself to create a press and publish it herself. It is a recasting of the iconic view of life at the North Pole, where Mr. and Mrs. Claus are more like us than different. They are not immune to the challenges ordinary people face. Santa wears jeans and a parka. They don’t age, but their elves do, which creates rich pathos in the story. Children are not naughty, for all children are innocent. And Santa worries about turmoil in the world as he prepares to depart on Christmas Eve, concerned that hot spots of conflict could disrupt his annual journey of love.

The following is an edited version of my far-ranging conversation with Pelletier.

Q: What sparked the idea for yet another story about Mr. and Mrs. Santa Claus?

A: I don’t know where the idea came from. Two Thanksgivings ago, “voices” started talking to me. It felt like another person living inside of me. I wondered if I could come up with a new version of Mr. and Mrs. Santa Claus. After all the staid versions we have, maybe they’re really a lot more like us than we realize.

Q: Why publish this book through your own press?

A: The Internet has changed everything about how to sell books. And people in marketing with the big publishers didn’t know what shelf to put it on.

I’ve never wanted to be just a novelist. I love the role as publisher. I did it before while I was living in Nashville. Nobody can care as much as you do about your own book and what happens to it.

Q: Will there be other books under the Ethel Books imprint?

A: It’ll be for my K.C. McKinnon stories. I already have four others in mind. They’ll all be illustrated, like “Mr. and Mrs. Santa Claus,” and have the same look. I won’t publish my Pelletier novels. And I’m not sure that I’ll publish any other authors, either.

Q: What’s the back story on “A Year After Henry?

A: My mother died in 2000. It was the biggest thing that ever happened to me. I came home for three months, to the house I was born in, to the house she died in.

For a year after she died, I didn’t want to write anymore. I was then down on my farm in Tennessee – it’s really isolated, way back in the woods. I didn’t see anybody for three months. I didn’t leave the farm for six months.

I remember later being in London, seeing a woman on television who was a “spiritual portraitist,” who drew people who were dead that were around her.

I’m not sure how I feel about death and an afterlife. Most of the time I think we’re just walking fertilizer. But I wanted to explore this. My mother was gone. And I probably wanted to see if I could follow her.

Q: Why set this book in Bixley? Why not fictional Mattagash?

A: My first three Mattagash novels take place in only a few days. I wanted to see whether I could write about characters and draw out the story over years. I needed another town. (Author) Susan Kenney, in reviewing my first book (“The Funeral Makers”) for The New York Times Book Review, wrote that in my book, “geography was a character, and place destiny.”

I think that Bixley is not a character. It’s just a canvas for people to come and go on. But Mattagash is a living thing.

Q: What is it with you and mailmen? There are mailmen in your Mattagash stories and mailmen in “A Year After Henry.”

A: Allagash is isolated. The only thing we had connecting us to the outside world was the mailman. We have just one road following along the river through the woods. Everybody would watch for the mailman. We were always waiting. When you’d see the mailman’s car poke its head around the turn, it was like the world had found you.

Q: You said to me in an email that your Mattagash stories “hurt your heart.” What do you mean by that?

A: When people ask, “Would you go back to your childhood?” most people say, “No, never.”

I would go back in a minute. I loved being a kid. I skipped a grade in school, and it pulled the rug out from under me. I spent a lot of time alone. I would go along the St. John River and rescue little trout in a tin can that had been stranded, putting them back in the river. I miss that. I miss the past. And my Mattagash stories remind me of that – of everything I learned here.

Q: Contrary to Thomas Wolfe, can one ever go home again?

A: I knew it wouldn’t be easy to come back here. And I’m glad that I spent the majority of my life away. But I have a great affection for my family, for my ancestors, for this town. I don’t know how many times I’ve looked out at this river and have thought, “My ancestors came up this river – in 1837.”

Why do we say that, “You can’t go home again?” I think it’s because age carries us into the future. Age takes us away from our own emotions. No matter where we are, we can’t go back to our old selves. They don’t exist anymore.

Frank O Smith is a Maine writer whose novel, “Dream Singer,” was released in October 2014. It was selected as a Notable Book of the Year in the literary fiction category by Shelf Unbound, an indie book review magazine. Smith can be contacted at:

frankosmithstories.com.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story