The Lewis Gallery of the Portland Public Library once again has mounted an exciting, informative and library-relevant exhibition: “The Pulps!,” an introductory survey of art made for the covers of pulp fiction publications.

For anyone who thinks American tawdry wasn’t born until reality TV, think again. “The Pulps!” is dirtier, cheaper and flossier than a drunken Snooki at a New Jersey lingerie outlet. As it should be.

Pulps had possibly the largest audience for popular culture literature in the decades just before television. Hundreds of pulp magazines were printed between the 1890s and the late 1950s, when the genre is generally considered to have gone bust (and with it, to a large extent, the short story genre). The pulps took their name from the cheap pulp paper on which they were printed (as opposed to the “glossies”) and were originally targeted at boys before re-gearing to the appetites of young men.

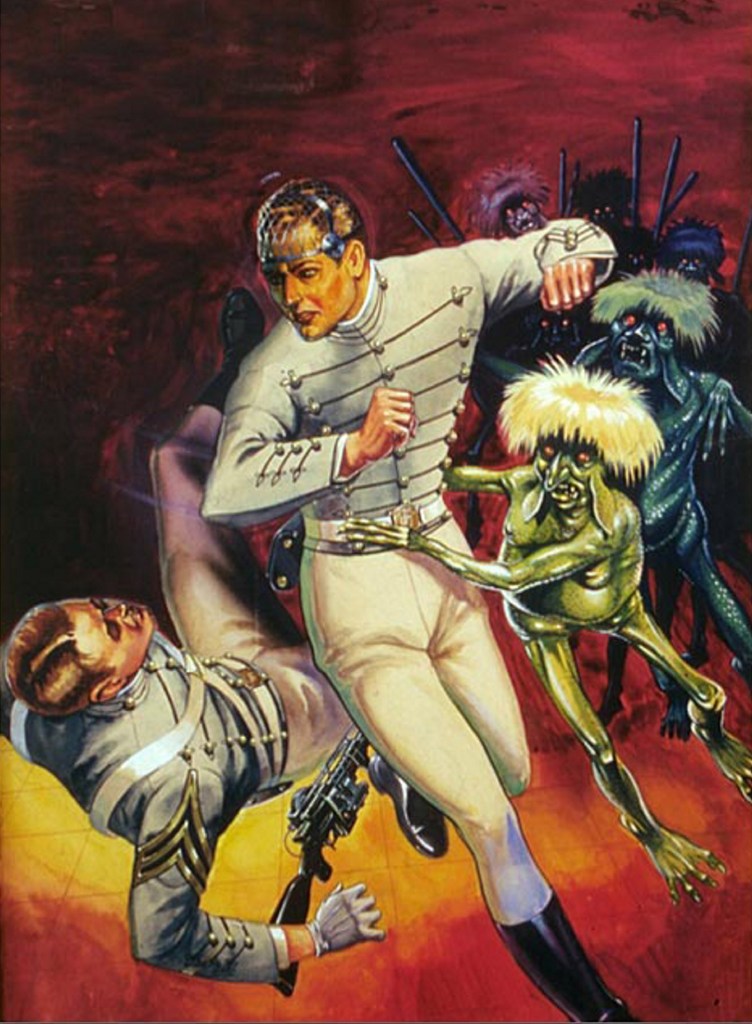

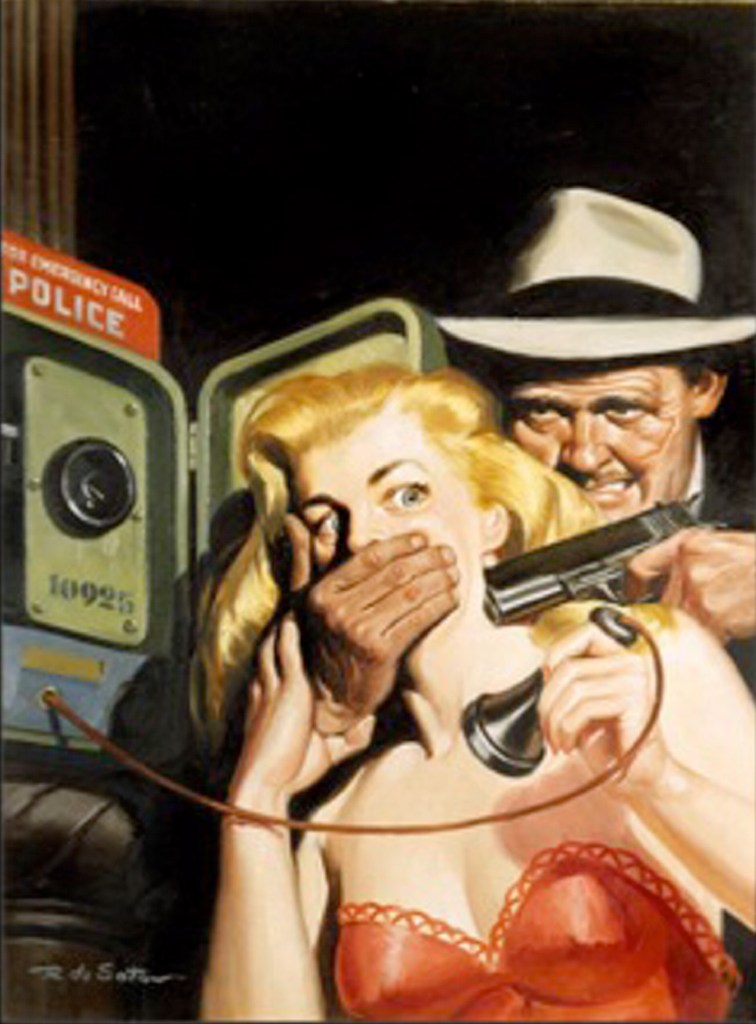

The cover paintings comprise a surprisingly complex mixture of cliché and creative, as well as an awkward blend of the morally heroic and the immorally titillating. One of the most insidious recipes for these cover paintings plays on the traditional hero-saves-the-damsel-in-distress model. But instead of seeing Saint George battling the dragon before a chained Andromeda, we find ourselves in the first-person position of the hero. We come upon a struggling, voluptuous woman whose clothes have been partially torn away by a misshapen villain who is surprised by our arrival.

What is different from the classical recipe is that our manliness includes attraction to the damsel. She is in distress in part because she is a beautiful, desirable woman – and that is not only why we need to protect her, but a preview of the reward for our heroic, moral participation. (The hero gets the girl, right?)

Hugh Joseph Ward’s “The Whisperers,” from a 1942 issue of Spicy Mystery magazine, for example, is set in a beef processing cooler. The damsel in distress is a buxom redhead whose hands are tied behind her head and whose viridian dress is down to mere tatters. The villain is a wart-faced hunchback with a long, curved knife pointed at her. But he is looking over his shoulder at an entering figure unseen other than the revolver in his (our) hand.

That would-be hero is us. And the scene is hardly over: The fierce look on the thug’s ugly face makes it clear things are about to get even uglier.

It’s a hearty blend of Horatio Alger and Sigmund Freud, and it’s all about adrenaline and primal instincts.

“The Whisperers” is shown with enough similar images that we get the idea not only of a type (a trope) but of actual genres – and that was precisely the point. Marketing is about setting expectations and whetting appetites, and the 50 or so paintings in “The Pulps!” represent one of the most successful marketing campaigns in American cultural history.

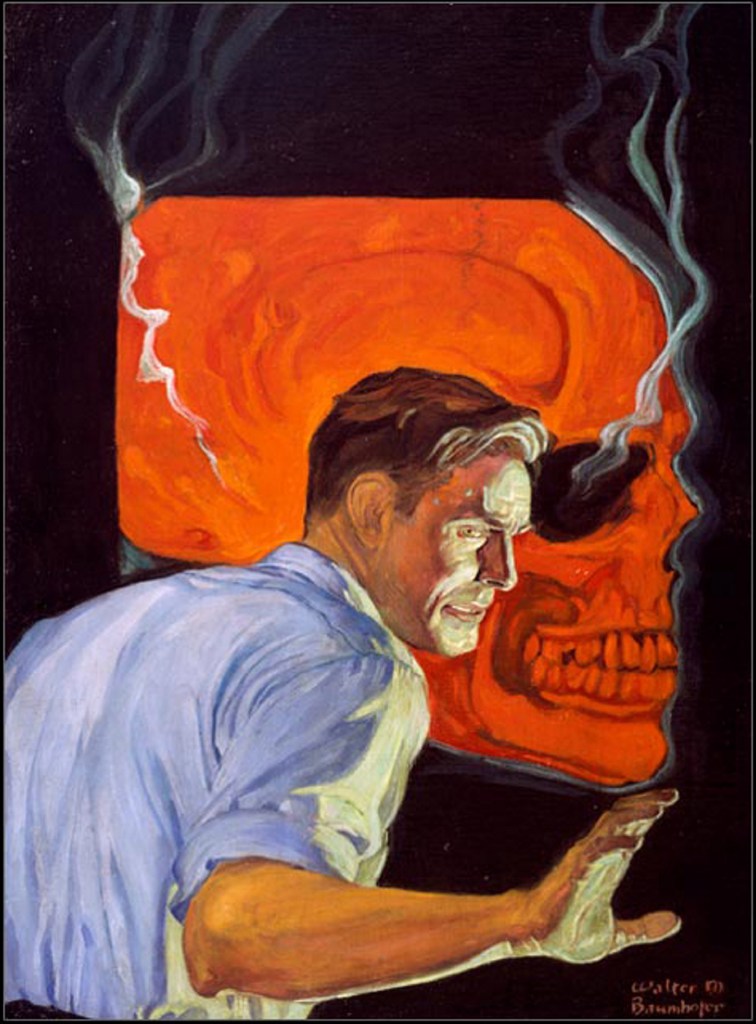

While there is a Snooki-esque quality to the target demographic, these are sophisticated images that essentially serve as the final punctuation on the glorious history of literary illustration pushed aside by film and television. These images are informed not only by N.C. Wyeth (who painted covers for the pulp Popular Magazine) and Howard Pyle in their beautifully structured and action-energized compositions, but by Freud and Surrealism in their sexuality-soaked psychological implications. These are practically programmed to get your heart racing – and they succeed in spades.

The paintings are framed together with at least one copy of a publication on which they appeared. This makes the show particularly interesting. Sometimes, for example, the book titles are part of the painting, though usually they weren’t. In one rare case, the modeling shadow under a woman’s breast is accentuated (for volume) when published on the cover of Frontier magazine, but otherwise the paintings are faithfully represented.

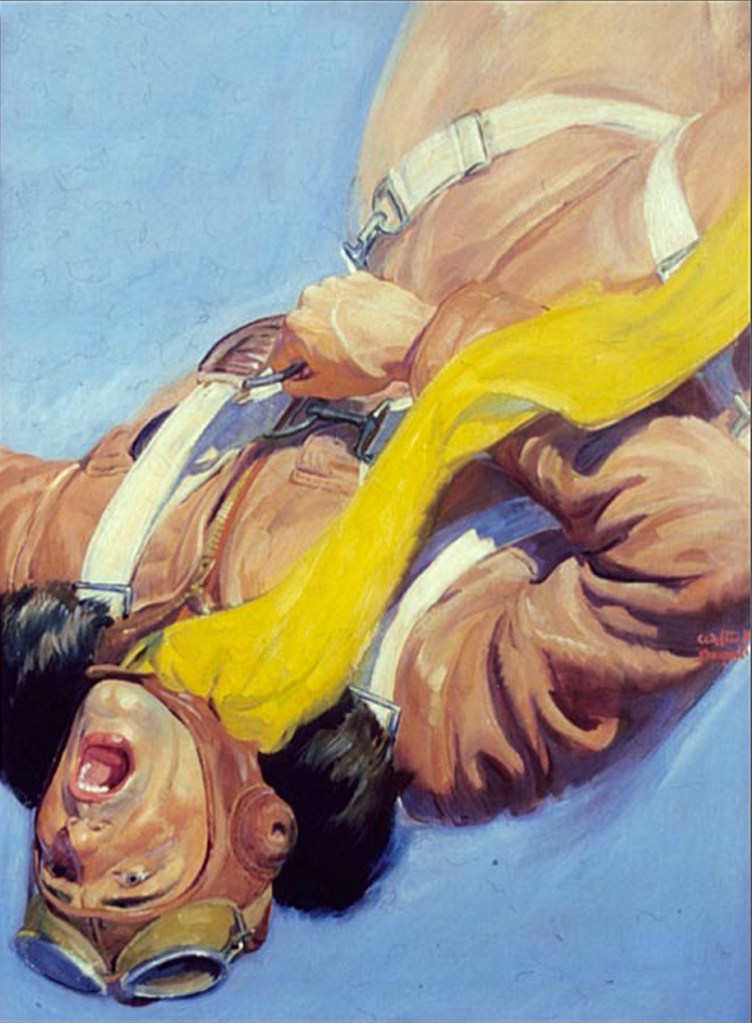

The paintings themselves are quite exaggerated, in part because of the theatrical lighting seen so often within them (stage lighting tends to combine cyan, yellow and magenta from different fixtures). The effect is particularly noticeable in works like Walter Baumhofer’s “Meteor Menace.” We see cyan highlights on the left side of the tied-up hero — particularly on his hair, typical of from-above stage lighting — and yellow light flowing in from the right. This not only adds to the sculptural forms and color sense, but cues the expectation of the exciting entertainment of a theatrical spectacle.

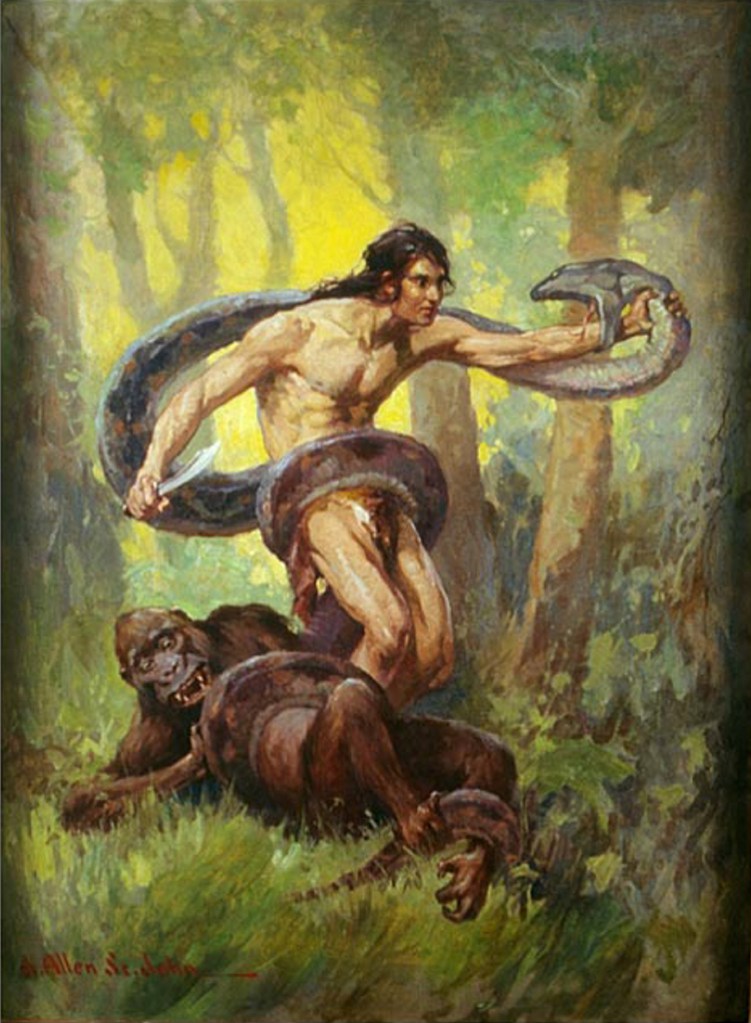

Many of the works were cranked out quickly for very little money, and this actually adds to the painterly interest of the show. After all, the brushy bravado of the slashing stroke is a core component of American painting, so the hurried aesthetic hardly detracts. But some are beautifully painted. After you see J. Allen St. John’s gorgeously colored image of a giant magic tiger on which rides a Bedouin and his damsel, for example, you won’t be surprised to learn that he was a student of William Merritt Chase and Kenyon Cox – two of America’s greatest painters.

The genre leans toward the psychological intensity of detective mysteries, serials like “The Shadow,” adventure and science fiction, but some of the World War II battle art stands out. My favorite painting composition, for example, shows a secret open-ocean meeting between a dirigible and a Nazi submarine. And one of the most fascinating displays includes two pulp covers and the aerial battle painting that was altered from taking place over a military airfield for Dare-Devil Aces to a secret, sinister hangar hidden in the mountains for the pulp Fighting Aces. (We know which came first because we have the second version of the painting hanging before our eyes.)

It is important to note that the pulps were the source of film noir’s gritty sexuality rather than the other way around. They are both, after all, swirling worlds of shadow, mystery, intrigue and complicated desires. And while we want to lean on Surrealism and the slick world of film, the pulps led the way. Here, we see so much of the struggling, curvy blonde being kidnapped (the damsels tend to struggle, which enhances the drama as well as their poses) that it behooves me to tell you that these are not cartoons for kids.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story